I graduated medical school in 1997, trained to offer skilled diagnosis and advise patients on the gold standard of care, always with the assumption that they would accept my recommendations. People come to the doctor wanting to know what’s best for them, and when we tell them, they should always act in their own best interest — though two millennia of history, multiple studies, and a whole book by Malcolm Gladwell disprove this theory. If I didn’t care so much about my patients, it wouldn’t break my heart when they chose to do the opposite of what’s best for them.

While shared decision-making has replaced the idea of the all-knowing doctor, physicians are still judged based on their patients’ “noncompliance ” — another term that has fallen out of favor even as the concept has remained firmly ensconced. In both medicine and child-rearing, we have an avid audience. In medicine, it’s CMS and the many health insurance companies judging the quality of our care. Their scrutiny adds another layer on top of my internal motivation to do the best for my patients. Likewise, as we drive our children around from activity to activity, we have a backseat full of invested relatives and neighbors. I internalized all their criticism, deserved or not.

When my patients didn’t want to quit smoking, I shared the preponderance of evidence of its dangers. I signed off on weekly letters from insurance companies advising me of my patients’ non-compliance with their statins. I went home defeated when my monthly list of patients with Ha1c > 9 came out. Each patient’s climbing Ha1c, their multiple excuses for why they couldn’t take the flu vaccine (“I’m allergic to pork” is and will always be my favorite,) their shock at being diagnosed with heart failure after years of not taking their antihypertensives -- were bad outcomes I took personally.

Meanwhile, my own children were growing up and exercising more of their own autonomy, adding much to my anxiety. As they navigated decisions about their high school identities and relationships, my advice became louder and more strident. I just wanted to save them from poor decisions with long-term consequences, but my efforts to beg, plead, and cajole them onto a different route served only to leave us all feeling frustrated and angry. Their response was to shut me out. I was sidelined right when they needed my support the most.

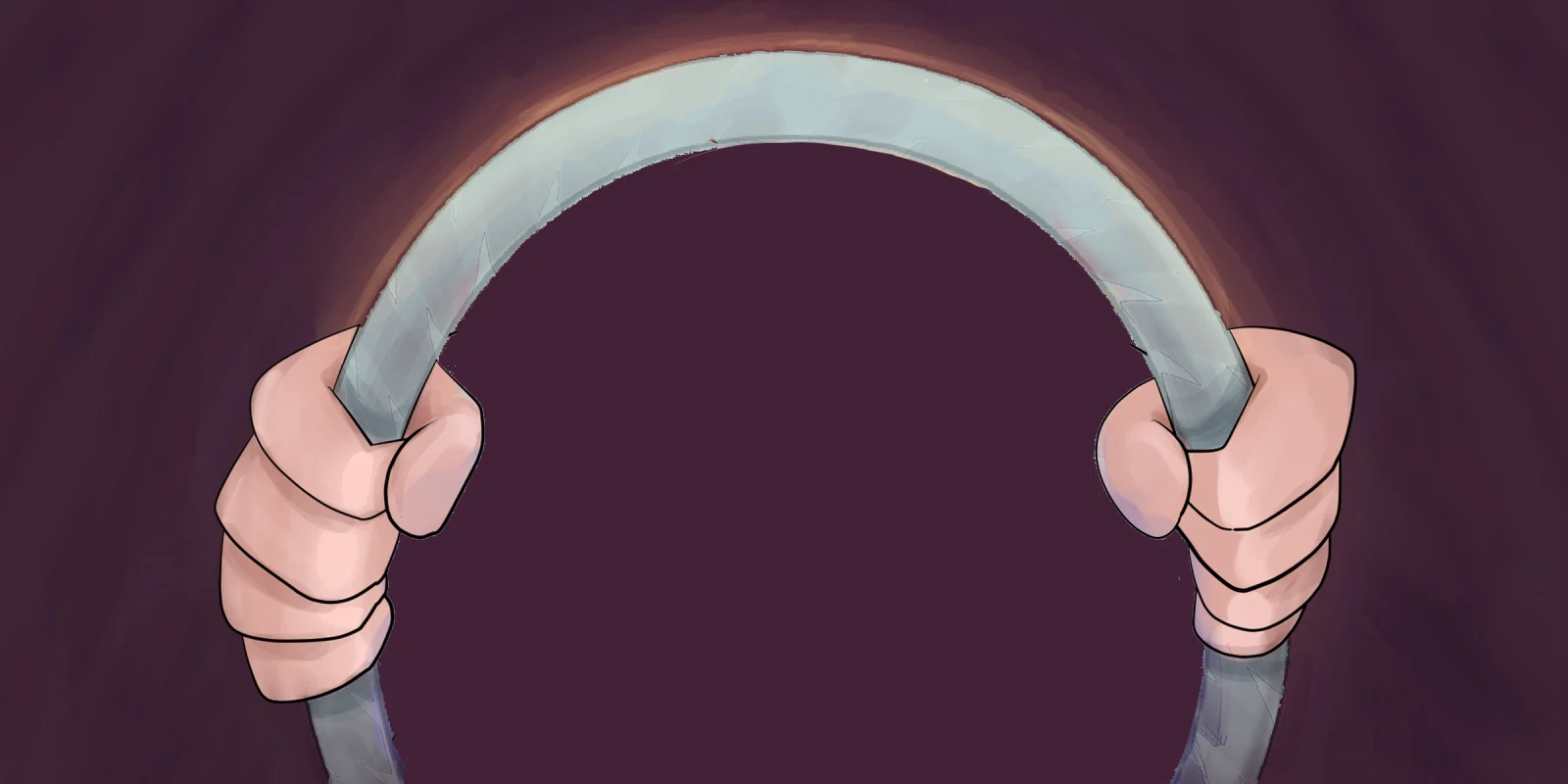

At the same time, they took driver’s ed and needed to practice their 50 hours of driving. In the midst of slamming my foot on imaginary passenger-side brakes and grabbing the oh-shit bar, I learned to pry my cramped fingers off the steering wheel of their lives. I transitioned from chauffeur to instructor and finally to navigator. I can tell my kids where to go, but they determine the route, the acceleration, and the speed. Sometimes they ask me for advice. Sometimes they listen to it. Just as often, they want to steer their own path, and I hold my tongue.

Applying this approach in the exam room has transformed my medical practice. Now I am a navigator, both in the car and the clinic. I recommend the shingles vaccine to my 50-year-old patient, but he declines. I code a Z28.21, “Immunization not carried out because of patient refusal.” When he comes back with the agony of shingles, I’m not responsible for the route he took to this new, painful destination, but I can recommend the quickest and safest way back to sleeping through the night. My 20-year-old patient would like to avoid pregnancy while decreasing her risk of STI? Then condoms with or without a secondary method is the best route. I code Z30.0, “General contraceptive counseling,” along with Z70.8, “Other sex counseling.” But my patient is the driver, and when she comes back in with chlamydia, it’s no reflection on me. Now, I recommend antibiotics for her and her partners and again provide condoms. When I recommend a statin for my patient with diabetes and the letter comes back three months later telling me they didn’t refill it, I code Z91.199, “Patient’s other noncompliance with medication regimen.” None of these codes let me off the hook from doing my job — making diagnoses and recommending appropriate therapy in a way my patients can understand — but they do remove the inappropriate blame I bear for their outcomes. I’m no longer the embarrassed passenger saying, “You should have turned right at the yellow house.” Instead I’m the map app, rerouting without bruised feelings when we end up at a bad outcome.

In addition to taking the weight of my patients’ poor decisions off my chest when I’m trying to fall asleep at night, the new role of navigator has provided another benefit. For whatever reason, my patients respond well to driving analogies. When I’m explaining how long-term high cholesterol contributes to plaque in the arteries, I explain how asphalt is laid down on the road. When I explain how weight loss benefits high blood pressure, I talk about how a bigger car (be it minivan or SUV) uses more gas. My patients understand these analogies and respond well to them. Likewise, when I say, “You get to choose which of my recommendations you take. You’re driving this car, I’m just the navigator,” my patients are grateful. They tell me they appreciate my respect. They often come back and say, “I’ve thought about it, and I’d like to go ahead with the colonoscopy.”

Now if there were only some ICD-10 codes I could paste on my teenagers’ foreheads to let their grandparents know how hard I tried.

When Ann told her parents she wanted to be a writer, they told her to get a back up job, so she became a doctor. Her debut medical thriller, The Match, won the Colorado Gold award for Best Mystery/Fiction, and was followed by Lost Things and The Code, both in the Kate Deming Medical Suspense Series. You can find her at https://anndominguezbooks.com.

Illustration by April Brust