A recently published paper caused breathless worldwide headlines about a “new” human organ hiding in plain site — the interstitium. It had me smiling because vascular surgeons, the good ones, recognize it and have been managing it for a long time. The interstitium is described as the space outside the cells. The new interest in it is like people suddenly obsessing about the stuffing in sofas. It is the body’s contained negative space and it is the most important organ because it was the first. It has been there all the while.

The genome and its expression, the organism, carry the past like hoarders. Look at a skin cell, and you see a nucleus and a cell membrane, the hallmark of the eukaryote, and the mitochondria that it took captive in eons past when it was a sea bacteria that was eaten and refused to be digested. The next most important step in evolution was multicellularity and specialization of these cells. The earliest efforts started as clumps of cells, but clumps have a limit — every cell had to have exposure to the outside and eventually these became spheres with a hollow internal space. Here was the first interstitium — the first inside, the first not-outside.

To these first animals, segregating an internal space different from the outer sea had advantages. You can concentrate nutrients inside when the seas outside are plentiful and use these when they are not. Add some structure and you have an endoskeleton — we share this with sponges inside this interstitium. As the organism became larger, this sphere flattened and some became animals with one pore ingesting and ejecting and others with two holes. We fall into a lineage that found transiting food through a cylinder to be advantageous. The nutrients were digested and absorbed from the worm into this internal space. The interstitial waters needed to be mixed as food came not from the outside but from this internal protodigestive tract, to have currents and streams. This was done with the development of tubes lined with smooth muscles that beat, interspaced with one way tricuspid valves. This primitive circulatory system is seen in many of our spiny sea cousins like starfish and sea cucumber, and lives in us as the lymphatics.

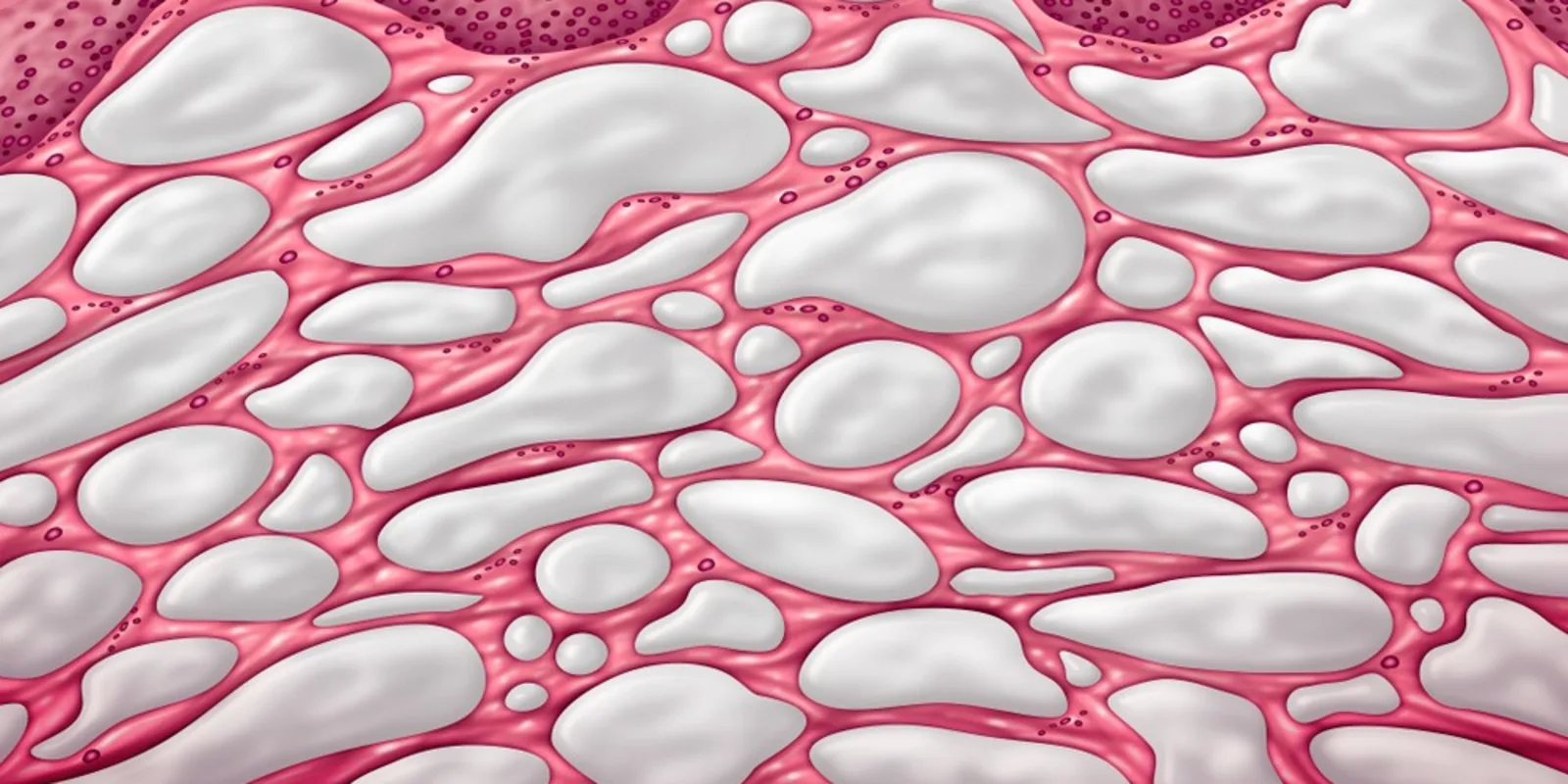

The interstitium is the remnants of this primitive sea creature that we carry with us, carrying within this pouch of internal sea. The fluid that fills blisters is a kind of briny sea water. When you see an edematous patient, observe the level of this sea by seeing where the edema ends. See how easy it is to milk out this edema out of a hand or foot, just as it is to squeeze the water out of a sponge. Edema is so common that it is easy to forget that so many diseases cause failure of the lymphatics — the bilge pumps of the body, and that on this tide may come many other things that makes the problem worse. In other instances, it may be just high tide in Venice, right before all the sewage gets washed out into the Adriatic.

The interstitium, as much as it was the progenitor of the circulatory system, is likely the foundational element of the nervous system. The various ion pumps are highly conserved and are useful only when concentration gradients are stable. The bioluminescent jellyfish is testament to this. Without the interstitium, cross membrane voltage potentials cannot be maintained. It is the bioelectric spark that life motion. If a planaria, a flatworm, is to have a soul, it resides in the interstitium. It is the spiritual ether bottled inside us. The ghost in our machine swims our portable primordial sea.

These old parts and compartments are hiding in plain site. The lymphatics beat and spread some of the nutrients from the gut into the venous system in connections up at the base of the neck. Both have been superseded by the portal venous system and the circulatory system but the lymphatics persist because there was no reason to abandon it, but possibly it is critical to our existence. The interstitium must play a critical role in homeostasis in the same way that the older autonomic nervous system plays critical subliminal roles by being both a buffer and a store. Every cell in our body is in contact with this inner sea as much as the first cell was afloat in the primordial one.

The interstitium is the final contact point between each cell and the organism as a whole. Oxygen does not go from alveoli to the skin without transiting the interstitium. Just as we are only beginning to grasp the complexity of genetics and the heredity of epigenetics, we are just noticing the interstitium. Up to now, it is as if we have been studying the outlines and histories of Byzantium, Rome, and Carthage, in isolation without studying the depth, composition, and currents of the Mediterranean.