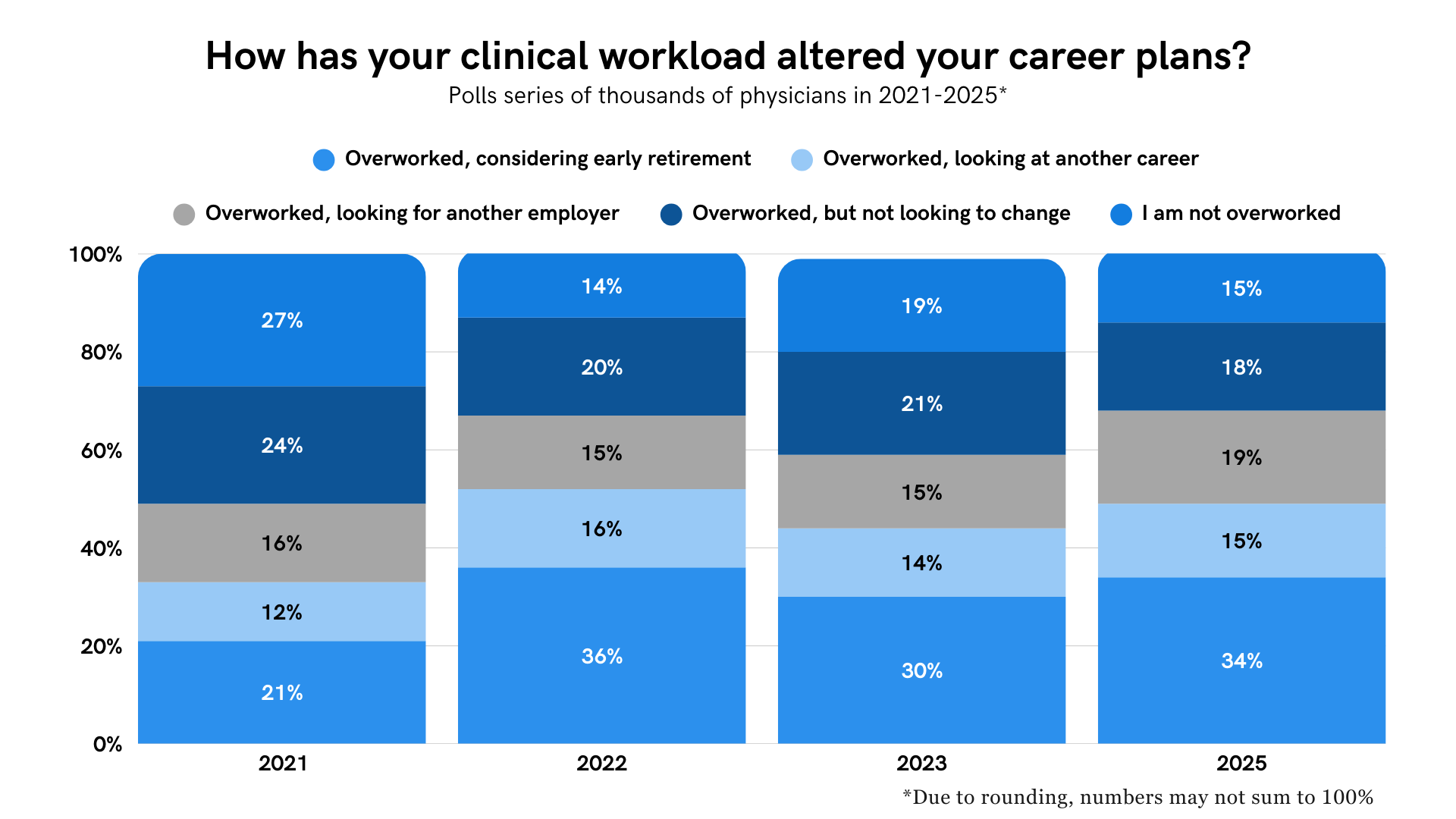

Despite the ongoing effort to address overwork in medicine, 85% of U.S. physicians still say they are overworked, according to a Doximity poll of 2,653 clinicians (including nearly 2,000 physicians) in May 2025.

The issue mostly appears to have worsened over the past several years. About 81% of physicians reported feeling overworked at the end of 2023, 86% in 2022, and 74% in 2021.

What’s more, 68% of physicians say the strain of overwork is pushing them to make a career change. This includes 37% who say they are considering early retirement, 17% looking for another employer, and 13% looking at another career.

For many physicians, overwork is not just about having an excessive amount of tasks and responsibilities, but also about the kind of work being prioritized, diminishing autonomy, and a system that often fails to deliver the level of efficiency physicians need for optimal care. “It’s not [just] overwork, it’s frustration with a new ‘normal’ of putting numbers over patient care,” said Laura Toner, MD, a pediatrician in New York.

Along with administrative burden, stagnating pay, and staffing shortages, overwork has been a major contributing factor to the persistence of burnout in medicine.

“In all the research we’ve been doing over the last 20 years, the number one contributing factor to burnout is work hours,” said Liselotte N. Dyrbye, MD, senior associate dean for faculty and chief well-being officer at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “Physicians overwork because the system remains inefficient and there’s simply too much work for physicians to do.”

Dr. Dyrbye acknowledged that burnout and work dissatisfaction were trending downward several years ago until the surge in workload during the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted that progress. Since then, physician overwork and, in turn, burnout have carried on, without a clear indication of letting up any time soon.

“There’s hope that we can get back to doing that really hard work of reducing workload, improving efficiency, and distributing tasks to the right people,” Dr. Dyrbye said. “But it requires system-level change, and it’s really hard to change systems.”

Demographic Differences

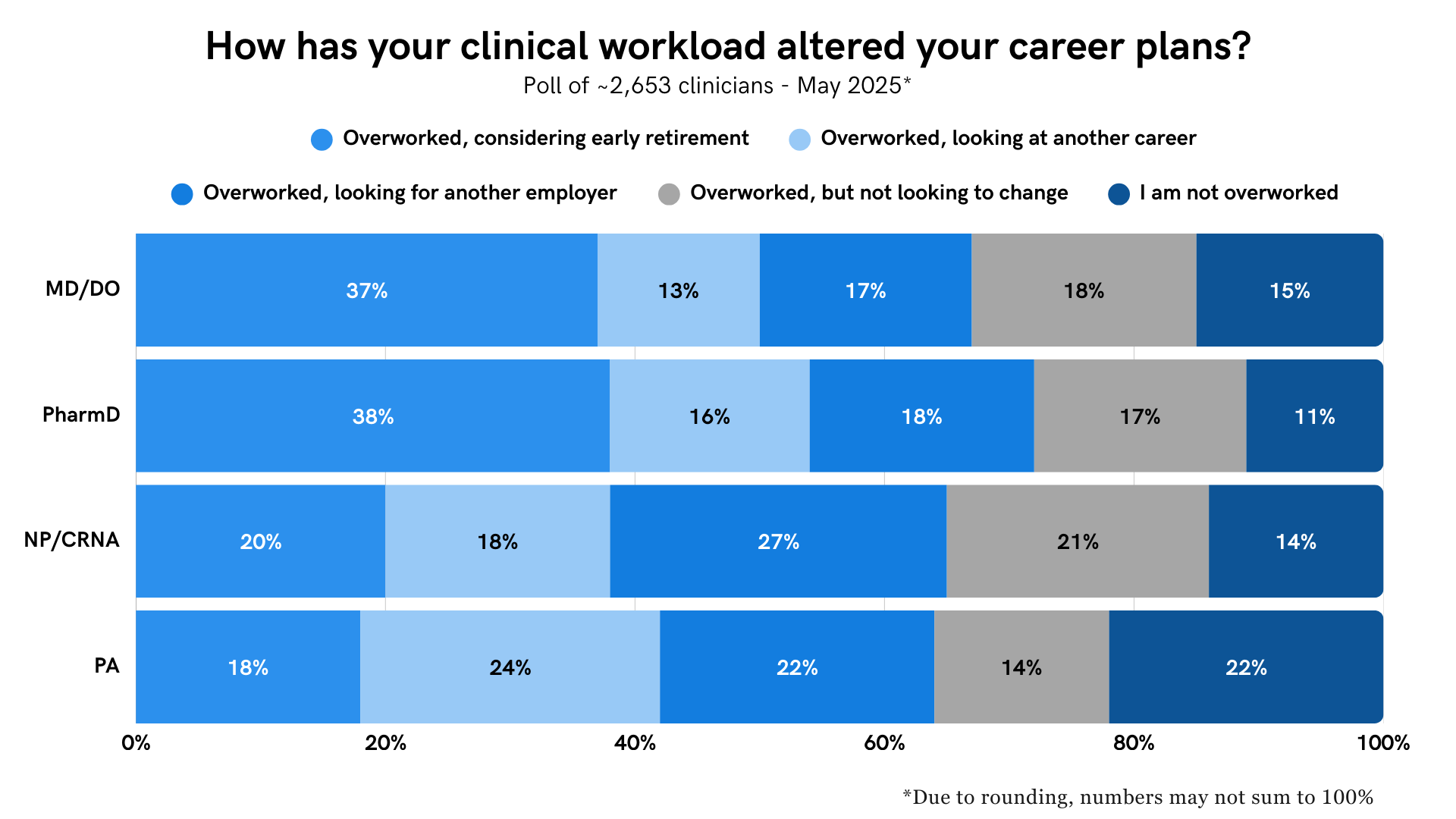

Overwork not only affects 85% of physicians but also the vast majority of other clinicians polled, including 89% of pharmacists, 86% of NPs, and 78% of PAs polled.

For physicians, overwork appears to be especially prevalent among women: 91% of women are overworked, compared with 80% of men. And overwork is driving 74% of women to consider making a career change, compared with 62% of men.

The sizable differences could stem from the elevated EHR burden women often face compared to men, or expectations associated with traditional gender roles both at home and in the workplace. Women are also more likely to work in fields disproportionately affected by burnout, like pediatrics.

However, “If you control for suboptimal experiences in the work environment, a lot of those gender differences go away,” Dr. Dyrbye noted. “The solution here is to support all young families and to help improve the work environment in general.”

Reports of overwork among physicians also mostly trend upward with age. About 78% of physicians 29 and under say they are overworked, compared with 85% in their 30s and 40s, and 88% in their 50s and 60s. (This percentage does drop to 75% among physicians aged 70 and older, likely due to their being closer to the average retirement age.)

Physicians in their 20s, 30s, and 40s appear more likely to respond to overwork by switching employers, whereas physicians in their 60s and 70s mostly favor early retirement.

Some physicians further along in their career have responded to overwork by reducing their hours and working part-time or locum tenens.

“Because of workload, I dropped to 87.5% full-time at age 50 and then to 75% full-time at age 55,” said Thomas Sobolewski, MD, an anesthesiologist in Ohio. “Working part-time has definitely decreased my feelings of burnout and has extended my career.”

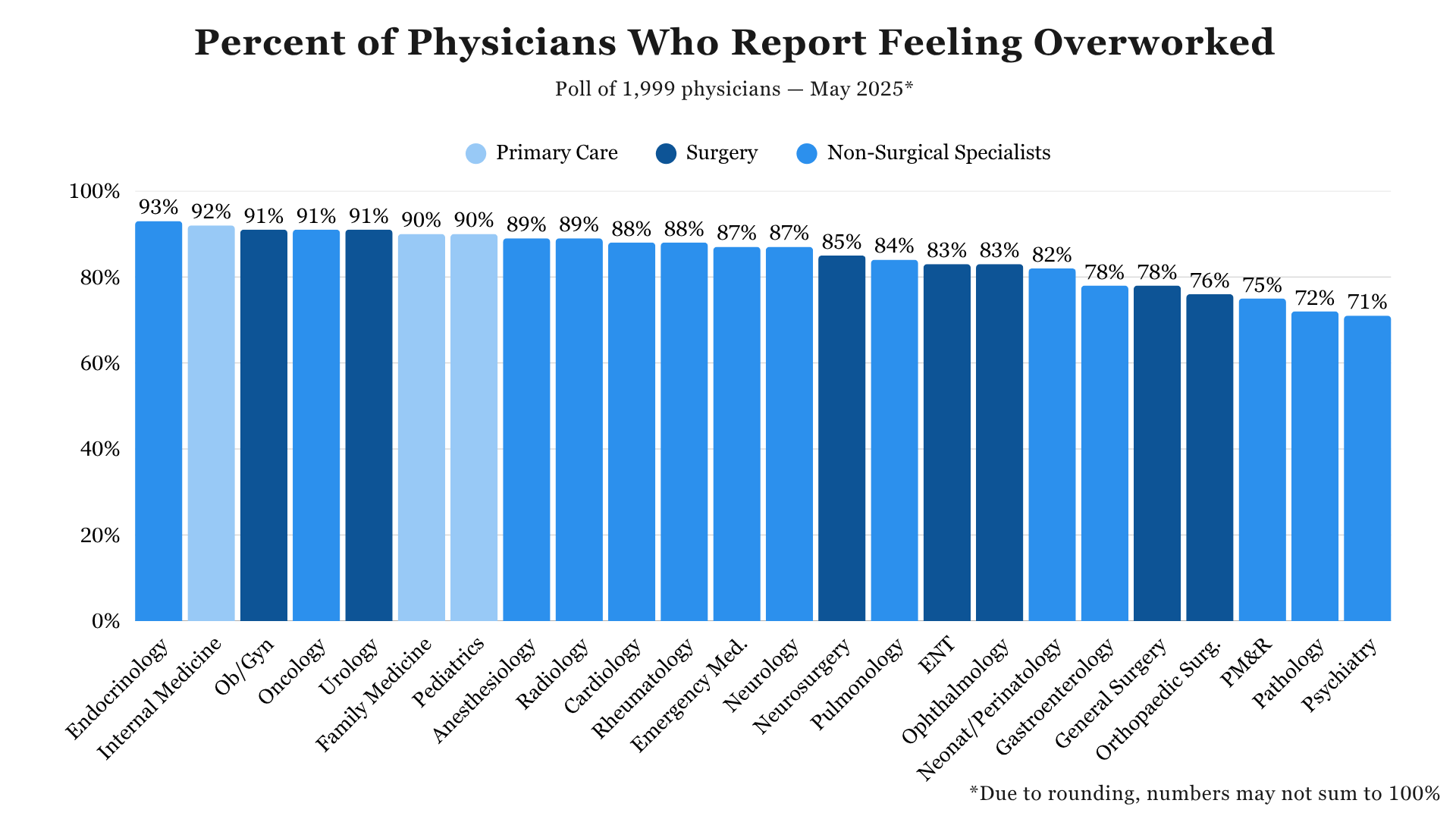

There are differences among physician specialties as well: 90% of primary care physicians say they are overworked, compared with 84% of surgeons and 83% of non-surgical specialists. Three of the top seven specialties most likely to report overwork are primary care specialties: internal medicine (92% of internists), family medicine (90%), and pediatrics (90%). Yet several other nonsurgical specialties — such as endocrinology (93%) and oncology (91%) — as well as surgical specialties — ob/gyn (91%) and urology (91%) — report similarly high levels of overwork.

Surgeons are slightly more likely to consider early retirement than are PCPs and non-surgical specialists. In contrast, PCPs are much more likely to look at another career (20%) than are surgeons (9%) and non-surgical specialists (11%).

The relatively shorter residencies and lower salaries may make a career change seem more viable for those in primary care. Though some, such as family physician Mark Hanson, MD, feel compelled to leave practice altogether: “Because of overwork … and the effect [it has] on time with family and other interests, I finally had to give up practice.”

Future Outlook

Still, these challenges have not deterred some physicians, medical societies, and national organizations from trying to better understand and address overwork and burnout in medicine.

The National Academy of Medicine developed an in-depth consensus statement that provides evidence-based ways to tackle clinician burnout. The American Medical Association offers free resources and “steps forward” modules regarding physician burnout. And the former U.S. surgeon general Dr. Vivek Murthy published an advisory on how to build a thriving health workforce.

In addition to these initiatives, Dr. Dyrbye has seen how several strategies have helped reduce physician workload.

One notable example is the use of team-based care, wherein tasks are distributed to allow staff to work at their highest level. For instance, a medical assistant might get patients ready for a visit and take their initial history, after which a physician performs any necessary exams and makes decisions, followed by a nurse assisting patients with orders and referrals to wrap up the visit.

There have also been major developments in technology designed to reduce physician workload, such as ambient listening devices that can help speed up note-writing as well as generative AI tools that can draft responses for physicians.

“There are some other AI tools in the sandbox that are trying to reduce the enormous amount of time we have to spend doing chart biopsies,” Dr. Dyrbye said. “That will ultimately help us spend more time at the bedside, which is really where we get meaning and what really helps elevate care.”

Another strategy centers on promoting a healthy culture through physician leadership. “One piece of the pie is working on our culture, and a lot of that culture is shaped by leadership behaviors,” she said. “So it’s really important to help make sure leaders are inspiring and motivating their team, equipping them with what they need, helping them grow, and treating them with respect.”

Amid shrinking margins in health care, hospital closures, and decreasing investment in well-being initiatives, it may be easy to be pessimistic about workload concerns. Yet Dr. Dyrbye has also encountered encouraging signs. She has seen some of the strategies above already start to make workloads more sustainable and cost-effective. But even more encouraging, for her, is seeing so many medical students and young physicians developing leadership skills and learning how to manage workflow quality and improvement early on in their careers.

“There’s a lot of enthusiasm and great talent coming into the workforce,” she said. “And that gives me a lot of hope.”

Illustration by April Brust