In my office, I see firsthand how deeply the wellness industry has become embedded into our daily lives. My patients come in with data from wearable devices such as rings, watches, and phone applications. One of my patients, no longer eligible for a liver transplant due to complications from end-stage MASLD, swears by an expensive “Dose” supplement she believes is helping her liver. Another patient brings in bags of dissolvable powders recommended by an Instagram influencer that she bought online to manage her PCOS. Equally concerning is the growing politicization of well-established medical practices, like vaccinations, fueled by voices from the wellness world.

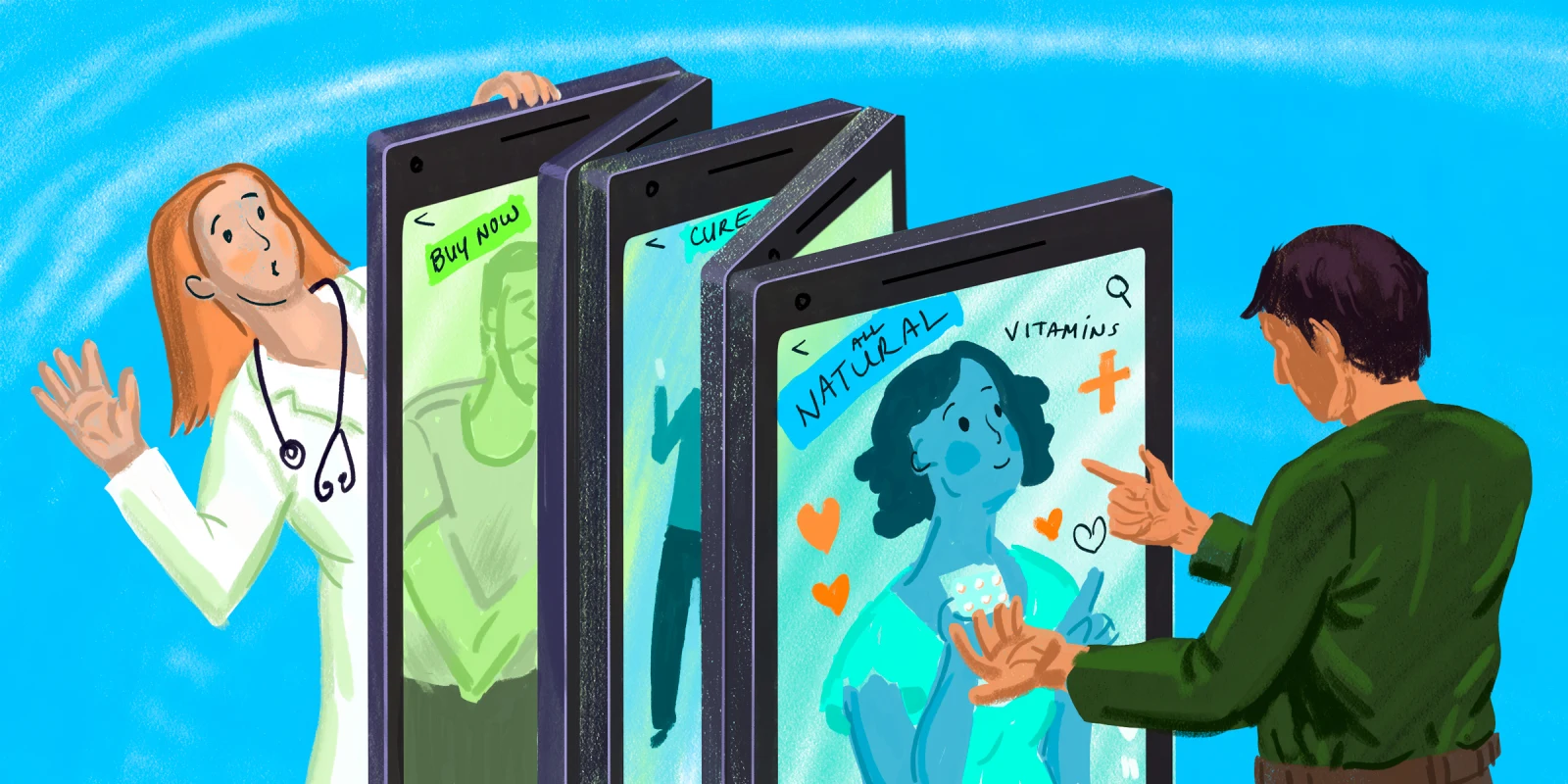

When evidence-based treatments are questioned and unregulated alternatives embraced, patient safety is at risk. But this doesn’t have to be a battle. How did we end up here, with clinical medicine being shunned and wellness being embraced? Western medicine and wellness are not mutually exclusive; they can coexist and complement each other. They could, and should, share a foundational principle: do no harm.

Understanding the Wellness Economy

To better understand the trends that influenced my patients’ health behaviors, I challenged myself to look deeper into the wellness industry to identify where our principles might align. According to the Global Wellness Institute, North America leads the $2.2 trillion global wellness economy. This includes sectors like physical activity, personal care and beauty, healthy eating, personalized medicine, mental wellness, workplace wellness, and more. Americans, on average, spend more than $6,000 per person annually on these wellness-related products and activities.

The demand for products in the wellness industry reflects patients’ desire to find practices and medicine that are both effective and align with their stance on health. According to a 1998 JAMA survey, patients turn to alternative and complementary medicine because it aligns with their values, beliefs, and philosophical orientations, rather than due to dissatisfaction with conventional medicine. These patients tend to be more educated and describe their health as poor. The review discusses several complementary therapies, including yoga, traditional Chinese medicine, music therapy, and guided imagery, and notes that there is evidence to suggest these practices can be beneficial in addition to standard treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, for cancer patients' treatment plans.

Yet this enormous industry lacks formal regulatory oversight. Unlike medications approved by the FDA or procedures reviewed through clinical trials, wellness products are often promoted through anecdotes, influencer marketing, and viral TikTok videos. Unlike supplements, pharmaceuticals need approval by the FDA before they can be sold or marketed. Supplements, on the other hand, do not undergo premarket approval processes, and the manufacturer is responsible for ensuring the safety of the product, rather than the FDA. Supplement companies need evidence that their products are safe and that their labels are accurate, truthful, and not misleading. This process is less rigorous than the FDA approval process and depends on the manufacturer, whose interest often lies in selling more product rather than upholding safety procedures.

Why Patients Turn to Wellness

Much of the appeal stems from a desire for agency and control in an increasingly complex and unsettling health care system. In the clinical world, patients face short visits, confusing bills, and long ER waits. They may experience medical errors or feel like their care is depersonalized. And in that space of frustration, the wellness industry steps in, offering alternative treatments to conventional medicine. If a patient feels dismissed by the health care system, they can pursue diagnostic workups or treatments for possible diagnoses not considered by doctors.

Patients seek community among others with similar symptoms. The placebo effect can offer meaningful relief for chronic conditions. Wellness regimens, such as supplements, ice baths, or personalized diets, feel tailored and empowering in ways our fragmented system often does not.

These wellness tools rely on feelings, emotions, and a sense of connectedness. For example, cold water exposure studies suggest a possible connection between this practice and an enhanced immune system, reduced insulin resistance, and improved stress regulation. However, the studies connected are heterogeneous, and participants may achieve these results with other factors, including active lifestyle, stress management, social interactions, and positive mindset. Therefore, patients continue this practice due to their feelings rather than evidence. By contrast, clinical innovation takes time, and our regulatory processes can be slow and exclusive, often overlooking women, minorities, and marginalized groups.

The Danger of Misinformation

When the wellness movement capitalizes on this frustration by rejecting safe, effective public health measures, it causes harm. It is estimated that 90% of Americans use social media for health information, and that this information can influence health behaviors, health beliefs, and decisions about seeking health care.

This 2021 systematic review found the highest prevalence of health misinformation on Twitter (X) regarding smoking products and drugs, as well as public health issues like vaccines and diseases. People relied heavily on Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, and Instagram during the COVID-19 pandemic for health information. The isolation of the pandemic and the uncertainty of the times created more trust in creators and social media claims rather than clinical care, which had to acknowledge the system's failures to patients.

A Call for Integration, Not Division

I want a health care system where modern medicine can coexist with the best of the wellness industry. We share common goals: combating chronic disease, promoting physical activity, supporting mental health, and enhancing dietary habits.

I encourage my patients to bring in their supplements, HRT formulations, or wellness tools. If they are safe and cause no foreseeable harm, I am open to incorporating them into care. My patients with chronic migraines show me daith piercings that have aided with debilitating pain. Another patient wants to continue to wear her Oura ring after an extensive conversation about birth control and the possibility of an unintended pregnancy. Patients will continue to incorporate these practices into their personal health behaviors and habits, and we need to be able to accommodate them in our clinical care, so as not to alienate patients.

The trillions spent on the wellness industry reflect a demand from patients for treatments that align with their personal beliefs and values regarding health care. These values include agency, bodily autonomy, and practices that promote harm reduction and prevention. They also want to give consent for any lab tests ordered, medicines prescribed, or procedures performed on their body. I would rather a licensed practitioner attempt to meet the demands of these patients rather than a misguided guru causing more bodily harm. Patients want to feel better, and I hope we can help them achieve this goal in clinical practice with a relationship built on trust and mutual interest in the safest, evidence-based care.

How have you dealt with patients who are interested in pursuing wellness trends over clinical care? Share below.

Dr. Kathleen Grant is a primary care physician in Athens, Georgia. She enjoys hiking, yoga, and playing ukulele with her husband. Interests in general internal medicine include rural populations, medical education, and cancer prevention. Dr. Grant was a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz