The patient's jaundiced skin throws me off as I thread the needle into his faintly pulsating wrist. There it is – a flash of fresh blood. Success. As I peel off my gloves and toss them into the bin, feeling a little like Kobe, the waveform collapses – and so does my heart. The nurse, lost in thought typing, suddenly shouts, “Code Blue.” The rest is a blur as the attending takes over, and I step back toward the wall. Later, a broken jingle loops in my ear as I wait on hold with the coroner’s office – oddly cheerful for a situation like this.

I turn to the fellow beside me. “Did I kill the patient?”

She leans back in her chair, fingers laced. “No. Medicine is all temporizing measures, anyway.”

There’s something unnerving about performing a death exam – familiar, yet never quite routine. The eerie feeling comes and goes as you step into the room, fading as quickly as it settles in your gut. During cross-cover sign-out, when a patient is on end-of-life care, the first question is often, “When will they pass?” And when the night float resident calls in distress, needing an attending to confirm death, there can even be a fleeting sense of inconvenience. Over time, this solemn act turns into a mental checklist – another task to complete amid the storm of responsibilities.

Until recently, I had never truly experienced the death of a close family member – at least not as an adult. Instincts kicked in as I recorded my aunt’s sodium on a fishbone chart, as if preparing for rounds like a diligent intern. The physicians in our family, across specialties and generations, huddled like offensive coordinators each shift, dissecting her evolving prognosis. Between us, we consulted multiple neurosurgeons for second and third opinions, debating whether transfer to an academic institution would be worthwhile. As her condition worsened, the difficult decision was made to pursue comfort measures. Despite the pain and burden of preparing to let go of a loved one, I observed an interesting shift: in some ways, we all became too comfortable. It’s not that the care disappeared – our vibrant, strategic dialogue softened, replaced by a gentler attention. Our hands, once hovering around IV poles or checking her nailbeds for pain, now rested in our laps. Everyone understood that life-prolonging interventions had stopped, but the intensity of care also naturally shifted. Yet comfort care is a time for a new kind of attention – not less care.

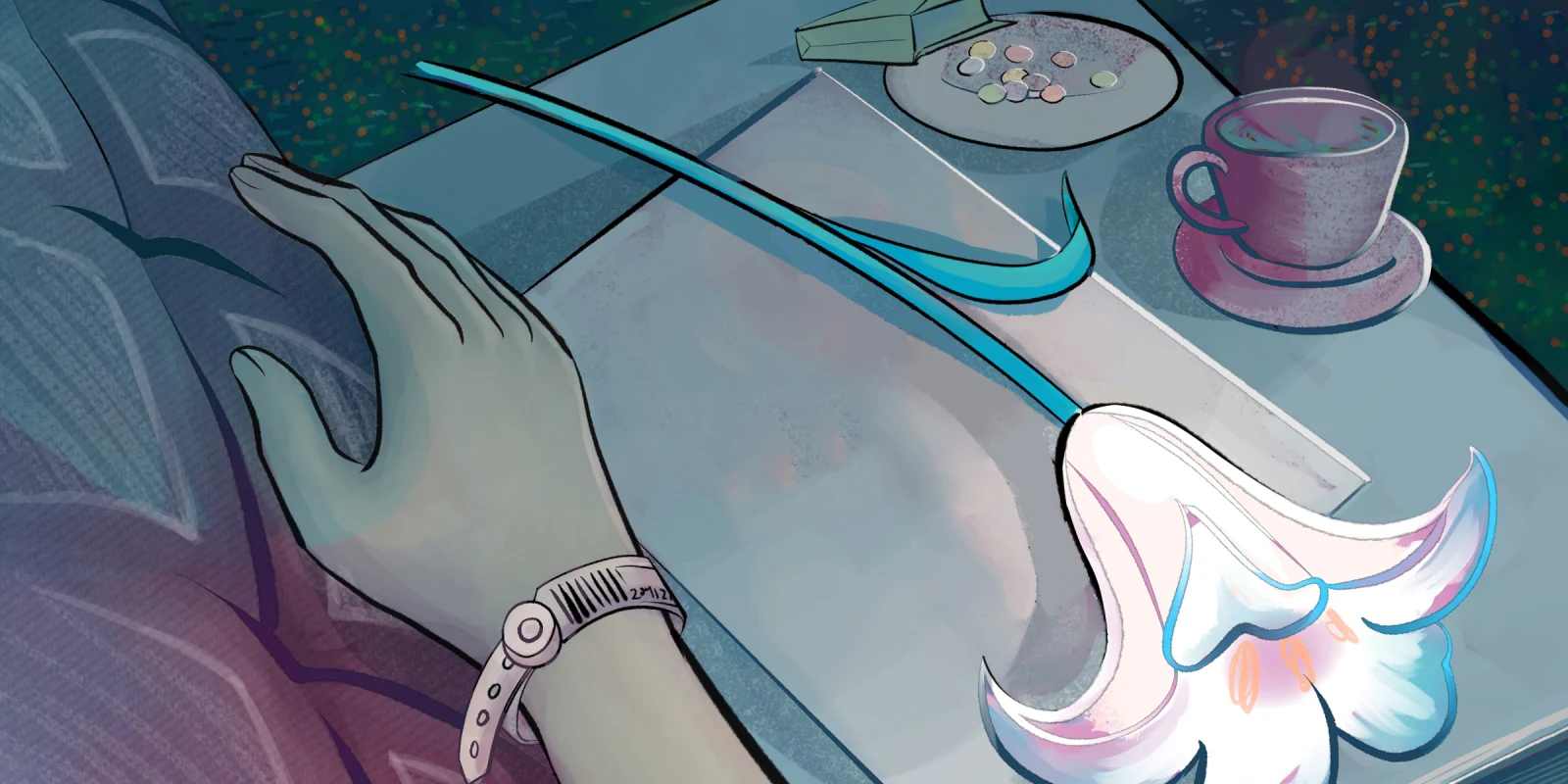

“Can I touch her?” an aunt asked, her voice childlike, as if seeking permission. Her eyes were swollen from sleepless nights, and grief was etched in every line of her face as she watched her sister and best friend die. Even the seasoned physicians in the family seemed hesitant to give guidance. One murmured “yes,” while another, with conviction, said “no.” So sat the family, chairs lined like an audience, uncertain of what to do. The monitors were silent, the room packed with family members. The tubes that once filled her mouth were gone, leaving a hollow opening. Her children stood at the bedside, wondering if covering her mouth might preserve her dignity. Each rattle of secretions drew uneasy glances, though no one explained what was happening. The growing sounds stirred panic, but all that was needed was a simple suctioning of her mouth. As days passed on the morphine drip, my aunt’s lips cracked from dehydration, and the nasal cannula flipped 180 degrees intermittently, as if desperate for the relief of a wet swab. Her abdomen grew rigid from days without a bowel movement, and her left arm swelled under the weight of gravity. I closed my eyes and imagined myself on that bed – how uncomfortable that must feel.

As she took her last breath and the surge of emotions settled, a different kind of transformation began. Being on the receiving end of “I’m sorry for your loss” opened the next chapter. Although kind, those condolences felt somewhat flat, inadequate, almost rehearsed – and I remembered that I had said the same words before. Perhaps in that moment, all I longed for was space to say she loved botany, that she once delighted in teasing me with impossible questions, or that she married a ship captain at the age of 20. Maybe even a “Tell me more about her” could have meant more – not a cure, but a soft catharsis. I realized that when a relationship with a patient or family extends even a few days, the “sorry” feels more genuine. But when it’s shorter, the words can sound procedural, cold. The white coat carries both power and comfort, and sometimes all it takes is pulling up a chair to make care profoundly human and healing. So much so that even a declaration of the time of death, rarely exact, can carry its own gravity – an emotional timestamp, immortalized for those left behind.

I sat at the foot of the bed on the sink counter, watching cousins – boys I last saw as children, now with full beards – paying their final respects, when it dawned on me: we, as physicians, are so skilled at caring for the living, yet often uncomfortable caring for the dying. Death is a universal reality in medicine; whether for an addiction specialist or a radiologist, it will be encountered. Just as many physicians dread the mid-flight announcement of “Is there a doctor on board?” we may feel similarly unprepared when confronted with dying patients. With that in mind, it is essential that all physicians develop basic competency in end-of-life care – regardless of specialty or scope of practice, so that patients and their loved ones may receive comprehensive, compassionate support in their final time. Because for someone like my aunt, we could have done just a little bit better.

Death is an unknown – a mystery that evokes fear and unease. When my aunt was terminally extubated, we were told she had only minutes left. Instead, she lingered — steadily defying expectations for two more weeks. But maybe that’s the starting point: to name that discomfort, rather than offering false assurances of understanding. And so, as my aunt once asked, is it OK to touch a dying patient? There is no algorithm like treating hyponatremia – it depends on the patient and the moment. In my aunt’s case, a tender hand on her arm, while telling her she was strong and loved, might have brought comfort. Hearing is believed to be one of the last senses to fade, even when someone seems unresponsive. In those small acts – a whisper, a touch – both participants may feel a sense of closure.

Not every death is peaceful. Some are abrupt and cruel – and so unfair. But in its quieter forms, maybe in a hospital bed or at home, when the body slows and the world grows still, death can be beautiful. It is one of the most vulnerable human experiences, when resentments ease, long-lost loved ones return, and we are reminded of the one truth that unites us all. It is a kind of unwinding – a release; like when a ship begins to sink, we lighten our load.

Death isn’t a medical failure. It’s an inevitability. For those who leave and those left behind, it marks a new journey of remembrance and making of meaning – as a pathos leaf that, once fallen, propagates again when given care. And while medicine can only ever be temporizing, there is something sacred in that final care – in showing up, witnessing, cleaning, touching, and talking. In the end, this is medicine too.

Dr. Naila Khan is an internal medicine physician practicing in both inpatient and outpatient settings in Southern California. She is passionate about lifelong learning and teaching – from patients as much as from students. She loves the ocean, croissants, soft Urdu music, and finds joy in hearing her loved ones laugh. Dr. Khan is a 2025-2026 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust