During my time as an orthopaedic surgery resident, my partner, Chris, had a basilar artery stroke. I arrived home from the hospital shortly before Chris complained of a severe headache and neck pain. It was only a few minutes before he crumpled into me in a diaphoretic, helpless state. I called 911 and held him in my arms, maintaining his airway. I waited for the sirens that I was used to hearing, anticipating the trauma to care for, but this time they were coming for him. I texted an EM physician on shift, so they would have the stroke team ready. I kept whispering, “It’s going to be OK,” trying to keep my voice steady.

The CT scan was initially negative, so at my insistence, the EM physician called the interventional radiologist to get a second opinion. Chris was in extensor posturing, and I held his rigid hand, waiting for an update. The consulting physician notified that Chris had a basilar artery stroke with a vertebral artery dissection. Chris was intubated and promptly taken for an embolization. I knew Chris’s chances of survival, much less with minimal sequelae, were small. I tried to maintain my composure while answering pages until my orthopaedic attending took over my call duties, for which I am grateful.

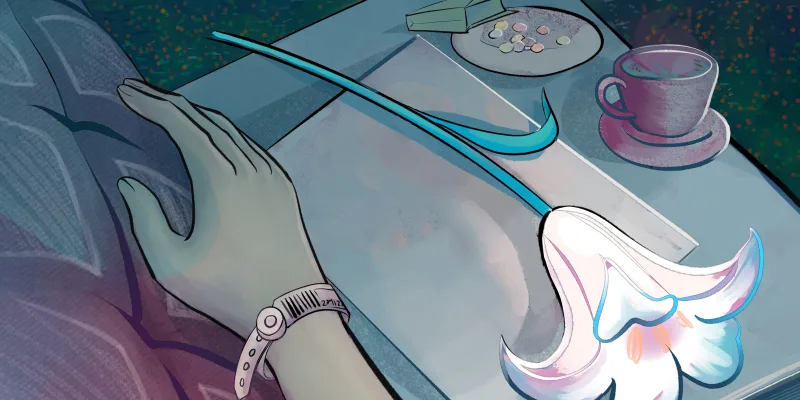

After the embolectomy, I met him in the ICU with the bright ventilator and monitor lights gleaning across his face. I took comfort in him squeezing my hand back, knowing he was locked in his bed but no longer in his head.

I learned about “locked-in syndrome” as a medical student with countless multiple-choice questions, but I had not prepared for the real-life test.

Within 72 hours of his stroke, Chris decompensated with Cushing’s triad symptoms. I expressed my concerns to the hospitalist, but I felt dismissed. They continued to increase the lisinopril dosage for his hypertension. A case manager even came in to discuss discharge planning with his parents and me, as he was deemed “medically stable” despite remaining with altered mental status, systolic blood pressure in the 160s, and being unable to participate in PT due to an uncontrolled headache. At one point, I gave him sternal rubs when he stopped responding and called for help. His nurse gave him Narcan, but Chris remained unresponsive. Impatient and scared, I contacted a neurosurgery teammate to ask if he would take a look at Chris’s case. Promptly, my neurosurgery attending was at the bedside to assess him. A new head CT scan showed concern for impending brain herniation. Chris was taken for an emergency craniotomy. His mentation and clinical status improved immediately postoperatively.

Once stabilized, Chris transitioned to neurologic rehab. He went from being bed-bound and struggling to hold his head up to ambulating with assistive devices. Videos were sent to me of his progress with PT, which helped me feel less isolated, as I was working a few hours away. It was emotionally draining to be away from my loved one due to my responsibilities as a resident. I did all I could to maintain my composure at work while feeling like I was barely holding it together internally. I received an outpouring of support from my co-residents and attendings, which I will always appreciate.

After a year of therapy, Chris learned to function independently. Despite seeing multiple specialists with over a million dollars of medical bills, there remains no clear answer as to why this happened to him as a healthy, active male. This experience was a powerful reminder of the uncertainties of medicine. If Chris had been found down by a stranger, he likely would have been presumed to have overdosed. He wouldn’t have been able to advocate for himself when the CT scan was initially incorrectly read as negative. Precious time would have likely been wasted on the lumbar puncture recommended by the EM physician or other tests due to the initial error by the radiologist.

I certainly have made mistakes throughout my training. This experience has taught me that one day, when I become an experienced attending, I won’t be immune to potentially hurting a patient despite my best intentions. We don’t always have the key to understand our patients’ diagnoses or personal struggles. No matter how well trained or experienced we are, we will not know all the answers.

If I didn’t have the privilege of knowing how to navigate the health care system, the training to understand his stroke, the professional connections at the hospital he was treated at, or the luck of being home from call when his stroke occurred, Chris likely would have died or been left with significant disabilities. Most of our patients aren’t so fortunate to have the health literacy or connections to advocate for themselves or their loved ones.

This experience helped me become better at counseling families and patients on difficult news, discussing uncertainties and setting expectations, understanding the many barriers to care for our patients, and understanding that I won’t know all the answers to care for my patients. I will always be grateful to the EM physician who listened to my concerns and sought another opinion. I also will never forget the countless nurses who helped care for Chris, such as letting me help brush his teeth, so I could feel included in his care.

I cried, hugging his main ICU nurse when I saw him while consulting on a patient after Chris had left the hospital. He made me feel heard, which I realize now is one of the most powerful gifts we can offer a patient’s loved one at the bedside. We can’t prevent trauma and suffering affecting our patients or loved ones, but we can lead with kindness, share when we don’t know an answer, ask for help, and maintain our duty to advocate for those who seek our help. Listening to a patient and their family can make a life-saving difference in whether they get the care they need. You already have that key.

How has listening to patients and their families impacted the way you provide care for your patients, or the way you approached a case? Share in the comments!

Dr. Janae Rasmussen is an orthopaedic surgery resident at Valley Consortium for Medical Education in California. She currently leads OrthoLink Scholars, a subgroup of MedLink Scholars, which is an organization designed to help medical students gain research experience and mentorship opportunities. She is passionate about health literacy, health policy, and how we can better improve patient outcomes by caring for the whole person.

Image by Lightspring / Shutterstock