Recently, there has been a surge of legislation on physician-assisted suicide, with some states and countries making it easier for individuals to end their life when it becomes unbearable. As a physician, I support these bills — but I also recognize that the decision to end one’s life isn’t always the patient’s alone.

I think all clinicians have spent time in the ICU with patients in the last days of their life who have no reasonable chance of recovery. To alleviate suffering in those instances and give those patients a dignified death, I think few of us can argue against. Things tend to get a little murky when we have patients who may have months, even years left who entertain ending their lives prematurely. I used to have a very liberal approach to these patients, believing that they should be able to choose their end without a government or institution interfering. However, over the years, my professional and personal experiences have made me question this permissive belief in physician-assisted suicide. Basically, I have seen family members who have skin in the game influence the decision that the patient alone should be making. It is, after all, the ultimate personal decision.

I remember the first time I witnessed the point in a patient’s life when they became “inconvenient.” I was called to the floor to evaluate an individual with metastatic cancer who had developed unrelenting periorbital pain. I was puzzled when I first saw them. There were no external signs and an MRI of the brain and orbits was normal. The spouse was there and was anxious. They were concerned about the mental status of the patient, who was distraught and inconsolable with pain. The spouse had made plans to discuss the case with the hospice service and entertain withdrawing all care.

I returned to check on the patient the next day. They had been sedated and given narcotics — they were definitely more peaceful than the day before. When I examined them, I noted vesicles on their scalp, which made me realize that they had zoster. I was relieved that the diagnosis was made and communicated the good news to the spouse that we had a reason for the pain and could treat it with antivirals and steroids. The spouse nodded but said they had already made the decision to start morphine and withdraw care. I tried to explain again that this was now treatable and, by all accounts, the patient should be able to recover from this and be back to their normal self, albeit with metastatic disease. The spouse thanked me and told me that they were going to stay with their decision. It was then that I realized that the patient had become inconvenient to their spouse, and that their spouse was ready to move on, even though the patient may have felt otherwise.

I was a little blown away by this experience. I sort of had an existential crisis where I was convinced that this was a common pathway in the end. At some point, we’re going to become inconvenient to our loved ones. We will become worth more (or be less expensive) dead than alive. There may be someone who has an incentive for our death — either financial or personal.

For me, the takeaway from discussions on physician-assisted suicide is that the decision should have absolutely no influence from anyone else besides the patient. If there is any person, government, or institution that may have something to gain from our death (consciously or unconsciously), they should be nowhere near us when that decision is being made. The “well-meaning” spouse may nudge us in that direction for their own gain. A health care system may facilitate the decision, as our premature death may cost less than continued care.

My personal experience with this was with my father’s death. My dad was a lawyer who was walking into the courthouse at the age of 81 when he tripped and fell, hit his head, and lost consciousness. He was taken by ambulance to a small community hospital and diagnosed with a subdural hemorrhage. They stabilized him, but his mental status was altered — he was alert, but could not communicate nor make purposeful movements. When I arrived at the hospital, I believed that my dad’s subdural hemorrhage needed to be drained, but the physicians on staff were very hesitant to do this since he was on anticoagulation, and they didn’t feel they had the best resources to handle a relatively complex case. I recommended that he be transferred to the tertiary care center about 25 miles away. One of my brothers’ responses was “That’s going to be expensive,” followed by “Who’s going to take care of him afterward?” It was then that I realized that my dad did not have a chance. He had become inconvenient: I lived too far away to care for him properly, and my brothers and sister had busy lives of their own. Though we didn’t mean to shorten his lifespan, the reality was that we had a choice to make, and that choice was compromised. He died about two weeks later.

That said, some of the reasons families encourage the shortening of a life, including by physician-assisted suicide, are less fraught. Watching a loved one experience pain can be a deeply disturbing experience, and I have had patients whose family members and spouses consider this route as a means of allaying a patient’s suffering. I sympathize with them, but I still believe that it is not their choice to make.

Relatedly, I have encountered instances in which lives are extended against the patient’s wishes. These are heartbreaking situations when a family cannot let go or is unequipped to make a very difficult decision. The common thread between ending a life prematurely and extending a life beyond what is best for the patient is that the patient’s wishes should be followed with no interference from outside forces.

In the end, there are things that can help: First, patients can make living wills. Second, all of us can talk to our loved ones about what our wishes would be in these difficult situations, since even with living wills, the family still has the final say. This communication and legal documentation can prevent undue extension of, or undue reduction of, a life that has little chance of recovery. A living will should be respected when it has been made under no duress. And the decision to end a life early should be made autonomously without any external interference.

Let’s hope none of us become inconvenient.

What are your thoughts on physician-assisted suicide? Share in the comments.

Dr. Richard Allen is an oculoplastic surgeon in Houston, TX. He practiced at St. Erik’s Eye Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden from September to December of 2024 as a visiting professor. He is an avid cyclist and enjoys spending time with his wife outdoors. Dr. Allen was a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

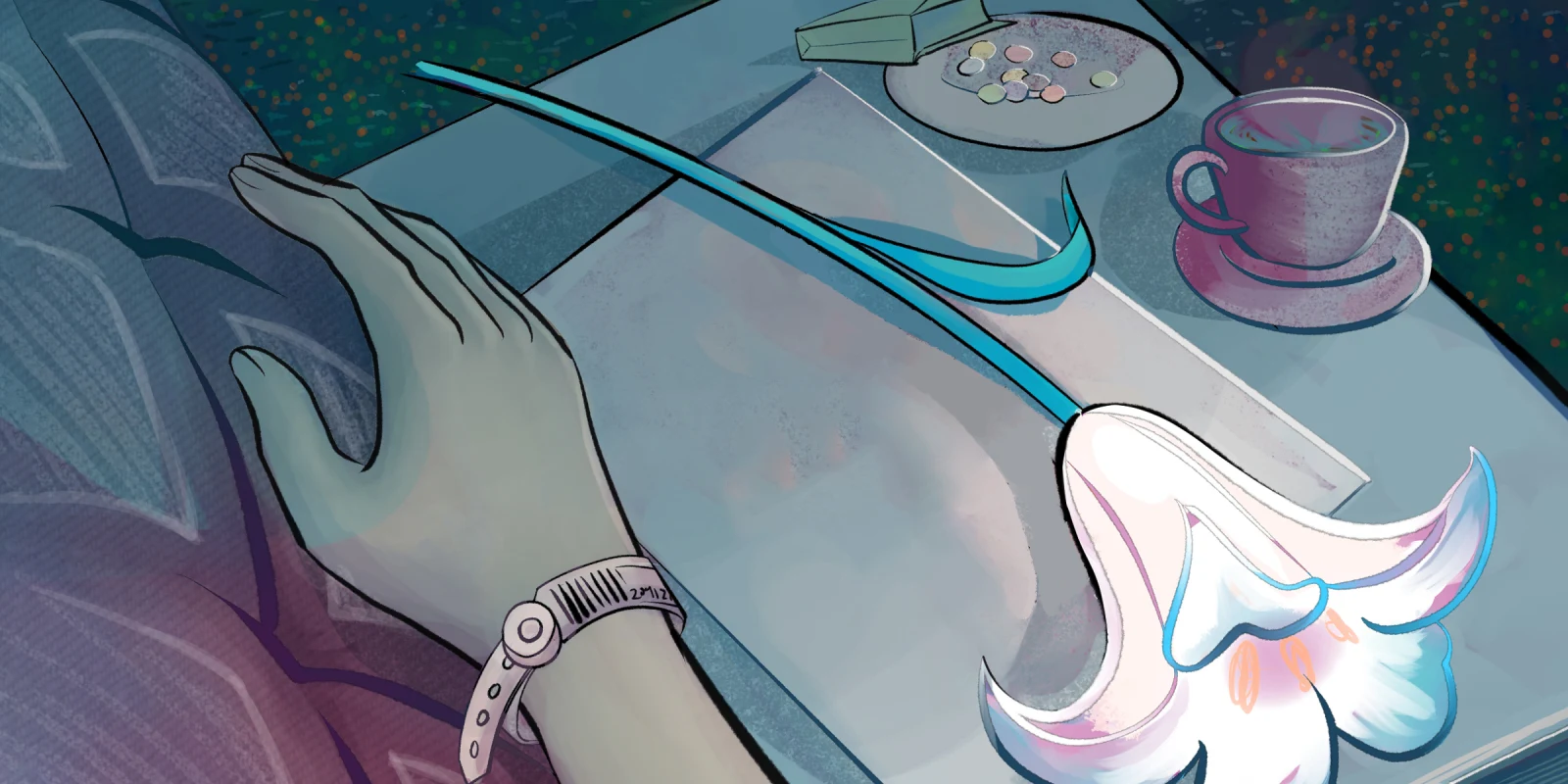

Illustration by April Brust