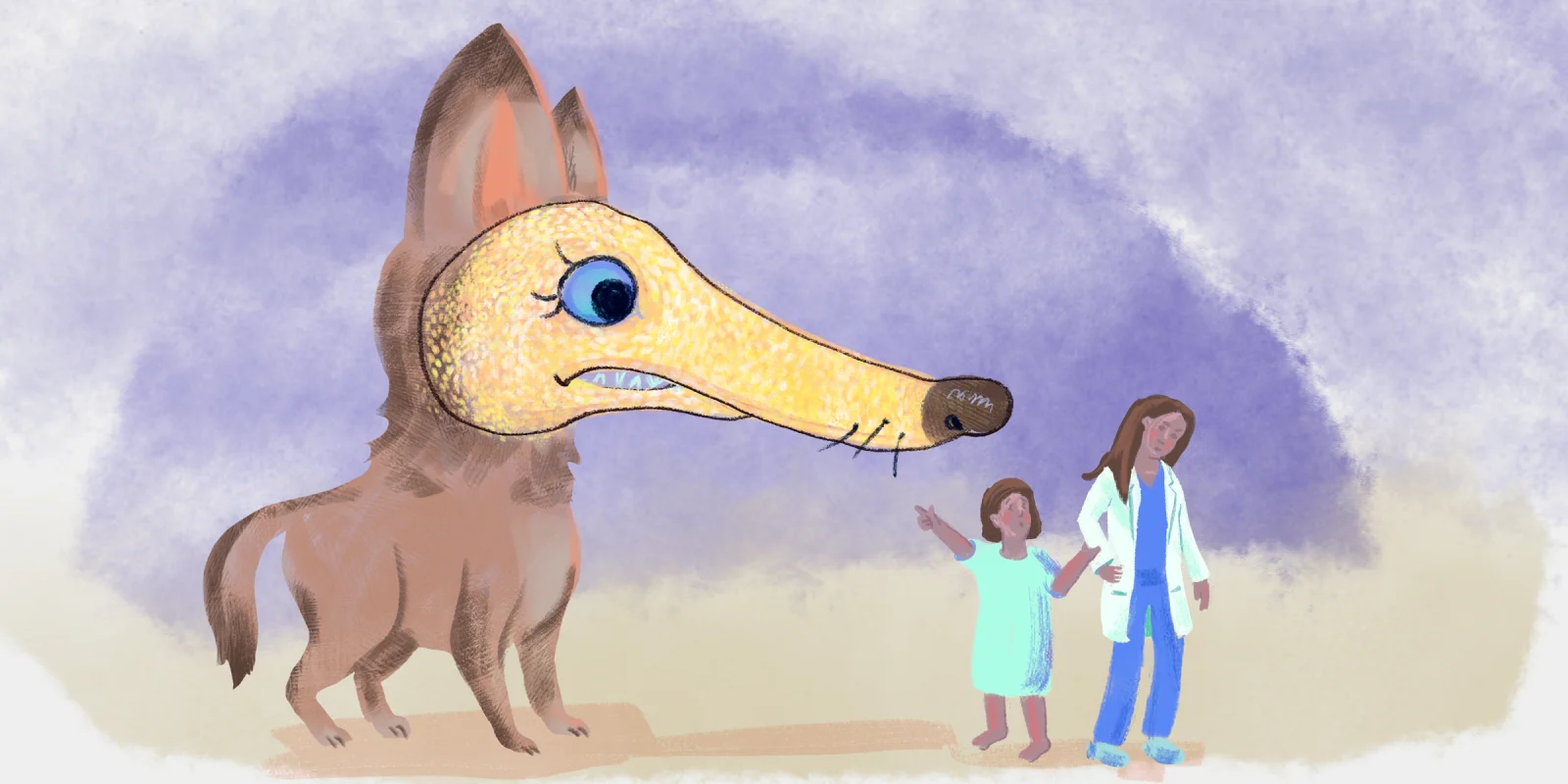

The story of "The Boy Who Cried Wolf" is a cautionary tale about the dangers of false alarms. The shepherd boy repeatedly tricks the villagers into believing a wolf is attacking his flock. When a real wolf finally appears, the villagers ignore his cries. The moral is clear: Repeated false alarms lead to skepticism and inattention when genuine danger arises.

But what do you do when it is a 14-year-old girl who cried pancreatitis, and not a boy and the threat of a wolf?

Sofia is a 14-year-old Hispanic teenager with a history of pancreatitis at 11 years old and a diagnosis of functional abdominal pain (FAP) the following year. FAP, as defined by the American College of Gastroenterology, is pain that cannot be explained by any visible or detectable abnormality after thorough examination and appropriate testing. FAP impacts 10-15% of school-age children and falls under disorders of gut-brain interaction, where pain arises from complex interactions between the brain and nerves in the GI tract.

Sofia presented to the hospital nearly monthly, either in the ED or admitted to the GI floor, for severe abdominal pain that left her unable to function at school or home. Given her medical history, most visits involved an evaluation for pancreatitis, but her lipase levels and imaging were always normal. She received pain medication, Reiki, and acupuncture, as well as consultations with the psychiatry, child life, and GI teams. Each time, she was discharged with improved pain.

She was the girl who cried pancreatitis, and I was now the villager.

I met Sofia for the first time during my second week as the resident physician on the GI service. It was her first admission of the month, and she was sure she had pancreatitis. Laboratory tests were drawn, and her lipase levels returned normal. She received pain medication, Reiki, and acupuncture and was seen by the psychiatry, child life, and GI teams. She was discharged home the following day with improved pain.

Sofia returned to the GI service a week later with similar abdominal pain and underwent the same evaluation as before. She was convinced she had pancreatitis. Her lipase level was normal. She received Reiki, acupuncture, and pain medications, then met with psychiatry, child life, and the GI team before going home.

She was the girl who cried pancreatitis.

Sofia returned the following week and was directly admitted to the GI service (again).

This time, her pain was more acute, localized, and intense. Her anxiety was palpable. As the GI resident who had cared for her before, it was disheartening to see her in this condition again. Was this still FAP, or was there something more? As her case unfolded, I was reminded of the importance of remaining vigilant for changes in a patient’s presentation that might suggest other underlying conditions. In her case of known FAP now presenting with worsening and more intense pain, it was crucial to rule out acute medical conditions. If and when those conditions were ruled out, it would be important to utilize the expertise of a multidisciplinary team, including GI specialists, pain experts, psychologists, and social workers to improve her chronic pain.

“Doc, this feels like my pancreatitis pain.” I had heard that before (twice). Both of her hospital visits in the last month had been due to severe abdominal pain. Each time, we reassured her and sent her home. But tonight, her condition seemed different. IV lines were placed, labs drawn, pain medications administered, and her vital signs closely monitored. Finally, the labs resulted — Sofia had pancreatitis.

She was the girl who had pancreatitis.

Throughout my time on the GI service, I often reflected on the importance of thorough evaluation in patient care. In the medical world, FAP can sometimes resemble the “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” fable. Patients with chronic pain often experience recurring symptoms that may not always reflect their underlying diagnoses. Over time, clinicians can become desensitized to these repeated complaints, attributing new or worsening symptoms to the existing chronic condition without a thorough reevaluation. Additionally, disparities exist in the pain management of children from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Sofia’s experience highlighted the complexities of chronic pain and underscored the importance of looking beyond the initial diagnosis for all patients, with particular attention to the disparities in pain management affecting children of color. The lesson here is not just about managing symptoms, but about truly listening to our patients and validating their experiences — regardless of how they may differ from our own.

Sofia's story teaches us that in medicine, just like in fables, we must always be ready for the wolf (or pancreatitis), even if we’ve heard the cry before.

What's a "boy who cried wolf" situation that you've dealt with? Share in the comments.

Dr. Tasia Isbell is a pediatrician at Boston Children's Hospital and Boston Medical Center. She enjoys cycling, traveling, and exploring the world through cuisine. She tweets at @DrTasiaIsbell. Dr. Isbell is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz