“Isn’t that what narrative medicine is? Just a study of nuance?”

Jennifer was discussing her thoughts on the course she had taken with me in the spring semester, where I had served as a co-instructor. She was a bright and insightful student, characteristics that prevailed as the pandemic disrupted our lives and forced us to relocate to Zoom. In the midst of that chaos, Jennifer had offered excellent analyses of the assigned reading and integrated outside research into her written assignments. Her hopes were set on medical school, and she believed that studying narrative medicine could potentially help her become a better physician.

As we debriefed several weeks after the course concluded, however, I could sense Jennifer’s frustration through my laptop screen. It was a frustration that I had seen before in many of my former students. A confusion about the field of narrative medicine and its very purpose.

“Well, yes!” I replied. “It is focused on nuance. Many people would say that nuance is exactly what is lacking in modern medicine.”

“I’m afraid it’s all talk, though,” Jennifer said. “A lot of close reading and too little action.”

My former student had given me much to ponder after our Zoom concluded. I agreed with her: If medicine was distinguished by its practice, then the humanities were marked by its lack. They existed almost as two entirely different cultures. I was supposed to be a teacher, but the truth was that I had my own doubts. I was plagued by a question that reappeared again and again in conversations with my students, a question that I still struggle to answer: How can we mobilize narrative medicine into action? And how can we prevent it from falling into lip service?

The central tenet of narrative medicine — as described by Dr. Rita Charon, a pioneer of the field — is close reading. In addition to taking on the role of clinical detective and diagnostician, the physician is a reader of both the patient’s story and body. Likewise, the patient becomes a text that can be interpreted and translated. A skilled physician evaluating a patient, then, is analogous to a skilled reader perusing a work of literature. Close reading is thus a muscle that needs to be trained and honed in order to result in optimal performance — just like the clinical skills required to practice medicine.

Narrative and storytelling can be found in every aspect of medicine if we look closely enough. Every clinical encounter, after all, involves a history-taking portion in which the physician interviews the patient and hears their story. The EMR is intended to translate the patient’s ongoing story into a digestible format, beginning with the chief complaint and ending with the plan. And patient case studies often focus on those suffering from unique and rare medical conditions — or in other words, patients with a previously unheard of story.

Narrative medicine can therefore be interpreted as not only a mode of clinical practice, but also a mode of theoretical inquiry that physicians can use to enhance the clinical encounter. “If patients’ reports do not limit themselves to answers in our review of systems,” Dr. Charon explains, “then we must be prepared to comprehend all that is contained in the patients’ words, silences, metaphors, genres, and allusions.” Practicing close reading allows us to read in-between the lines, to look at our patients with nuance, in order to gain a fuller understanding of their story.

Narrative medicine follows in the footsteps of other narrative-based efforts to improve modern medicine for both physician and patient. The ongoing pandemic has brought renewed attention to the fields of narrative medicine and medical humanities, but interest in similar practices has steadily been growing for years. A majority of these approaches emphasize reading, writing, and the study of literature in order to better grasp the contours of storytelling in the context of health care. Such a focus can not only improve our skill of close reading, but also potentially transform us into more compassionate physicians who can communicate effectively with our patients.

Nevertheless, the precise utility of the medical humanities and its allied disciplines continues to be hotly debated by physicians and educators alike. Many have argued that narrative-based pedagogy has no place in medical training, while various studies have still been unable to determine the effectiveness of narrative medicine on trainees’ professional development. And sometimes even medical students themselves have claimed that such interdisciplinary efforts are, in their own words, a “complete waste of time.”

This ongoing conflict reminds me of what C.P. Snow first called “the two cultures” in his influential 1959 Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge. A renowned novelist and chemist himself, Snow lamented the growing divide between the sciences and humanities and feared that this separation came at a disservice to the rest of the world. “Closing the gap between our cultures is a necessity in the most abstract intellectual sense, as well as in the most practical,” he reasoned. “When the two senses have grown apart, then no society is going to be able to think with wisdom.”

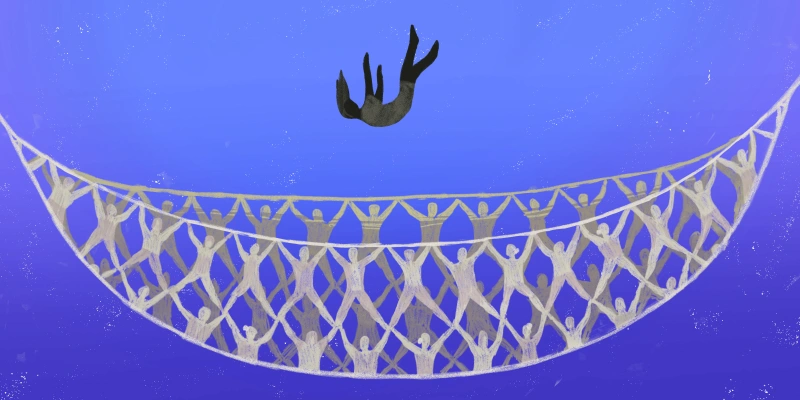

Are we doomed forever to pit medicine and humanities against one another? If narrative-based practices have shown us anything, it is that these two fields do not need to be placed in diametric opposition. Indeed, perhaps the very intersection of these disciplines can serve as a space for something more generative — more stories told and more stories heard, all handled with nuance and fortified by close reading.

I often think back to Jennifer and our conversation that day. I am no longer the teacher with any lessons to give. Like me, she is currently in medical school on the path to becoming a physician. We are both students now, the two of us wrestling with the application of narrative medicine and straddling the divide between two cultures. In spite of our doubts we still recognize, as Charon explains, that "there is little in the practice of medicine that does not have narrative features, because the clinical practice, the teaching, and the research are all indelibly stamped with the telling or receiving or creating of stories.”

To learn more about medicine, I think, is to learn more about narrative medicine and vice versa. It is an ongoing process that is always in flux, a journey toward a destination that is still unknown. Maybe Jennifer and I, along with anyone else working in health care, are eternal students in search of ways to bridge the divide and make it smaller — for the benefit of all us.

Where do medical humanities fit in in patient care? Share your opinions in the comments.

Saljooq Asif, MS is a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine. He is also a Lecturer in the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, where his scholarship focuses on the broader health humanities in relation to narrative ethics, racial justice, popular culture, and more. He is a 2021-2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect privacy.

Illustration by April Brust