Empathy is universally recognized as an essential trait for physicians, yet the practice of medicine often seems designed to erode it. The term is used liberally in medical training, held up as an ideal, but rarely given the time or space to flourish in clinical practice. Numerous studies have shown that empathy begins to decline as early as the third year of medical school, coinciding with increased clinical responsibilities, emotional exhaustion, and the everyday pressures of modern health care. While medical educators encourage empathy, the reality of rushed appointments, electronic documentation burdens, and the emotional toll of witnessing suffering leaves little opportunity to engage in the kind of deep, meaningful connections that patients deserve.

In the “Star Trek” original series episode “The Empath,” first broadcast on December 6, 1968, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy encounter a silent, otherworldly mutant whose very existence revolves around absorbing the pain and injuries of others. She is more than just compassionate; she experiences suffering as though it were her own, taking it into herself in a way that heals the afflicted. Unlike mere sympathy or detached concern, her empathy is visceral, sacrificial, and immensely healing. Watching this, one cannot help but wonder: What if physicians were truly able to embody such empathy? And what happens when they cannot?

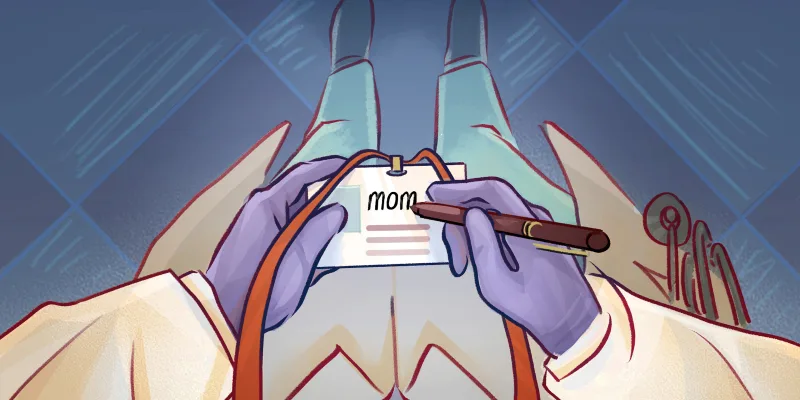

Medicine often requires a balancing act between feeling and detachment. Some might argue that a physician who takes on the suffering of their patients too deeply would be paralyzed, unable to function effectively. And yet, the opposite — complete emotional detachment — leads to the physician burnout, cynicism, and moral injury that plague the profession today. Medical students enter their training bright-eyed and idealistic, eager to comfort the sick, only to be conditioned into efficiency-driven automatons who check boxes, dictate notes, and triage suffering into manageable units. Somewhere along the way, the deep, instinctive human connection that makes healing possible is lost.

The empath offers a stark contrast. She does not selectively ration her compassion; she embraces suffering fully at great cost to herself. Physicians, too, are often expected to bear witness to pain, yet they are trained to suppress emotional responses for the sake of maintaining composure and objectivity. Unlike the empath, they do not have the luxury of supernatural healing abilities. If they absorb too much pain, they risk emotional collapse; if they shield themselves too well, they risk becoming indifferent. This tension defines the modern clinician’s struggle: how to care deeply without being consumed by the suffering of others.

Admittedly, I was caught in this quandary early in my career. Bearing the full weight of patient care on my shoulders caused considerable anxiety. I sought help from my mentors. Assurance that I was a good doctor was insufficient. Guidance from faculty members didn’t sink in. Textbooks and self-help books seemed inadequate. Advice to distance myself from patients — and, alternatively, to not fear getting too close to them — was rejected.

The loss of empathy in medicine is not merely an individual failing but a system-wide issue. The pressures of productivity, the dehumanizing nature of EHRs, and the relentless demands of an overburdened system leave little room for the kind of presence and attunement that true empathy requires. It is not that physicians do not care; it is that they are stretched so thin, drained by bureaucratic demands and institutional constraints, that their capacity to care is diminished. Empathy, once abundant, is gradually eroded, leaving behind a hollowed-out version of the healer they once aspired to be.

When Kirk, Spock, and McCoy return to the Enterprise, reflecting on their encounter with the empath, “Scotty” listens to their discussion about whether they would ever meet someone like her again. He remarks that she must have been “a pearl of great price,” and they agree. The phrase, drawn from a biblical parable, suggests that something of such profound worth is rare, invaluable, and not easily found. Perhaps McCoy understood this from the beginning when he gave her the name Gem. Whether he was aware of it or not, he recognized her extraordinary nature — her rarity, her beauty, her intrinsic worth, and the self-sacrificial empathy that made her unlike any being they had encountered. Like a precious stone formed under pressure, her ability to take on the pain of others without hesitation was something remarkable, something not easily duplicated.

The same could be said of true empathy in medicine today. It is precious, yet elusive. Those physicians who still carry it — who still manage to preserve their ability to connect deeply with patients despite all the forces working against it — are as rare as Gem herself. Their presence is a gift to their patients, their colleagues, and the profession as a whole. Perhaps McCoy, in naming her, was offering an unspoken acknowledgment of the very thing he feared losing within himself. After all, McCoy was a doctor!

The lesson of “The Empath” is not that physicians should aspire to take on their patients’ suffering wholesale but rather that they must fight to preserve the ability to connect in a way that is both meaningful and sustainable. This means making space for reflective practices, ensuring that medical training does not strip away the very humanity it seeks to cultivate, and advocating for health system changes that allow physicians to practice medicine with both competence and compassion. The ability to heal is not merely about technical expertise but about presence, listening, and bearing witness to suffering in a way that acknowledges pain without being devoured by it.

In the end, physicians may never be like Gem, absorbing wounds and making them vanish. But they can — and must — work to reclaim the lost art of empathy, to resist the forces that strip medicine of its humanity. To heal others, they must remain, above all else, human themselves.

How do you balance empathy with the emotional demands of practicing medicine? Share in the comments.

Arthur Lazarus, MD, MBA is a former Doximity Fellow, a member of the Physician Leadership Journal editorial board, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry in the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is the author of several books on narrative medicine, including “Every Story Counts: Exploring Contemporary Practice Through Narrative Medicine” and “Narrative Medicine: Harnessing the Power of Storytelling through Essays.”

Image by fedrelena / Getty