Dialing my grandparents' familiar phone number, I reflected on the enduring significance of these 10 digits. Over the years, my grandparents have instilled in me an appreciation for the sharp wit and intelligence of the elderly. However, I remain troubled by the pervasive assumption in medicine that older individuals invariably suffer from cognitive decline. Through sharing my story, I hope to encourage clinicians to view elderly patients in a new light, free from preconceived assumptions and ageism.

My story begins with my four wonderful grandparents. Our consistently close relationship has been fundamental to both my personal and professional development, inspiring me to teach modern technology to senior citizens and ultimately pursue a career in medicine, where my greatest joy lies in caring for elderly patients. The inspiration to teach about modern technology began when we gifted my grandparents an iPad for Christmas. Despite my grandparents' complete lack of experience with technology, we patiently taught them how to use the iPad. It felt akin to teaching them a new language, but the rewards were immense. Wanting to replicate these results, I founded a non-profit organization where I encountered many similar heartwarming stories. This firsthand experience dispelled the misconception that elderly individuals struggle with technology due to cognitive decline or a lack of intelligence. Their difficulties primarily stem from a lack of exposure, easily overcome with patience and consistent practice.

As a paramedic and medical student, I have found joy in working with elderly patients, appreciating their life stories and wisdom. Unfortunately, not all colleagues share this appreciation, frequently labeling elderly individuals as demented, even without a formal diagnosis. Too often, I witnessed elderly patients being excluded from conversations regarding their own care, under the assumption that all elderly patients suffer from some form of dementia, casting doubt on their intelligence, wit, and decision-making capacity.

The ignorance in this thinking became evident to me through an embarrassing personal experience early in my paramedic career. I responded to a 911 call for an elderly gentleman with dementia who had fallen, and I immediately began questioning the patient's daughter about what led up to the fall. Responding in a slightly angered tone, she said, "Why don’t you ask him? He’s sitting right there!" Feeling embarrassed, I turned to the patient and realized he could coherently describe the events leading up to the fall. In fact, he was witty enough to poke some fun at me for making a fool of myself. I encourage clinicians to learn from my experience and avoid assumptions. Instead, presume that all patients are devoid of cognitive impairment until evidence suggests otherwise. At the very least, you’ll save yourself from an awkward moment.

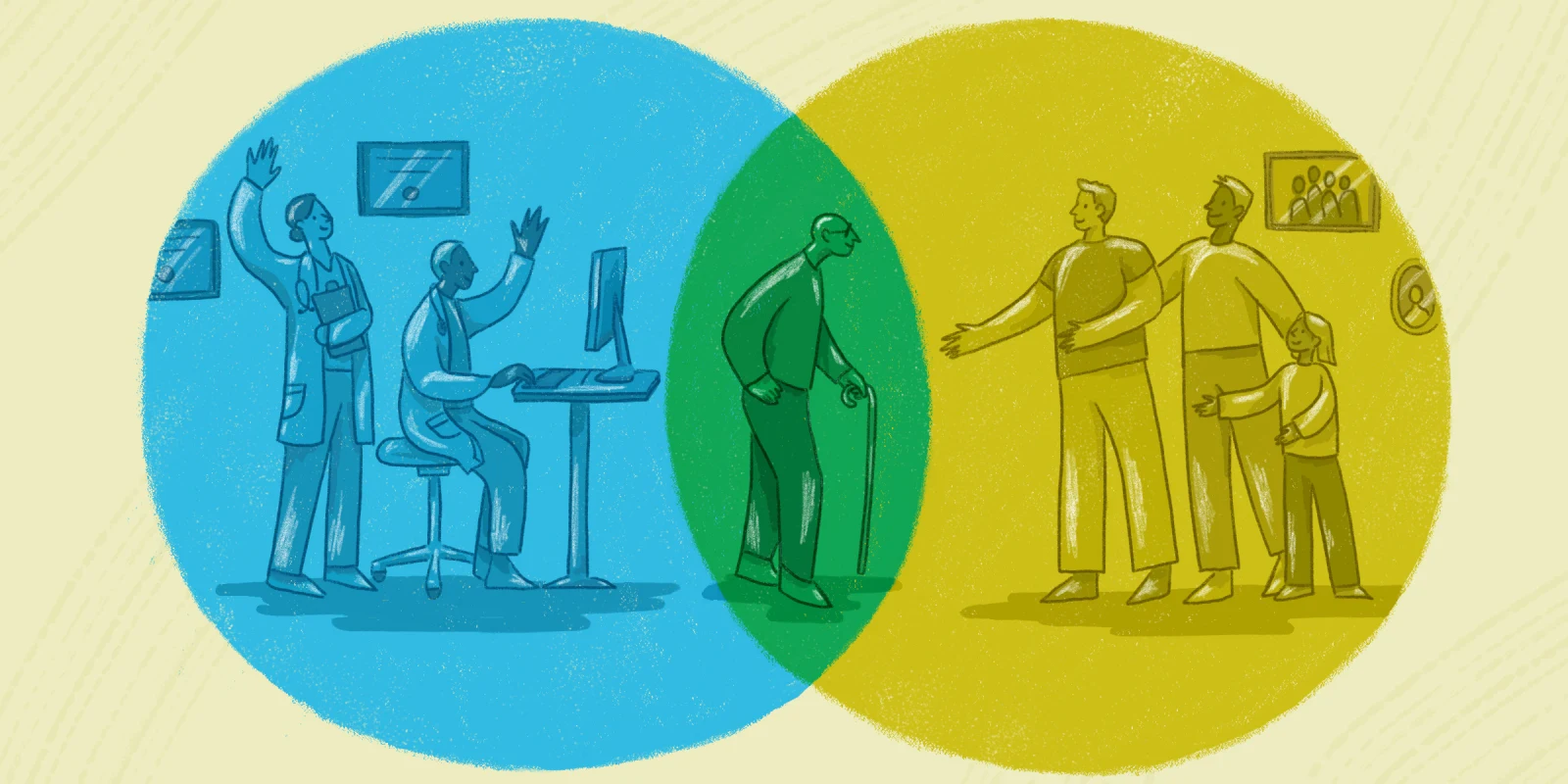

The beautiful thing about ageism in medicine is that we, as physicians, can have a positive impact. The notion that older age is associated with inevitable cognitive and physical decline, coupled with a decrease in quality of life, is fundamentally flawed. Consider the two types of intelligence: fluid and crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence, which pertains to problem-solving and generating new ideas, peaks in adolescence and gradually declines around middle age. In contrast, crystallized intelligence, which is the knowledge, vocabulary, and reasoning derived from experience, actually tends to increase with age. Furthermore, while there may be a dip in happiness during middle age, it is far from the end of the story. Research shows that happiness follows a U-shaped curve with the highest levels of happiness at young and old age, contrary to common misconceptions. These changes are not universal and depend on various factors, including an individual's ability to adapt to old age, intergenerational connections, and resilience. This is where we can intervene. Many of us are young and can foster intergenerational connections through simple bedside conversations. We can actively involve patients in care decisions, respecting their values and preferences, helping them adapt to the challenges of later life. Additionally, we can contribute to building resilience by making elderly individuals feel valued and appreciated.

As I look to the future, I’m reminded of my inspiring mentors who consistently display a commitment to improving care for the elderly. I vividly recall an attending physician on my service beautifully navigating a conversation about hospice care with an elderly patient and their family. She seamlessly blended her medical expertise with the patient’s and family’s values, guiding them to arrive at their own decisions about care. She truly listened to the essence of her patient, as conveyed through stories of who they were in the weeks, months, and years preceding their terminal diagnosis. Although her compassion was not curative, it certainly seemed to ease the pain of an incredibly difficult situation. In addition to observing my mentors, conversations with like-minded classmates in the hallways have instilled confidence in the future of medicine. The responsibility lies with us to be catalysts for change, encouraging more physicians to emulate the compassionate approach to elderly care that I witnessed in my attending physician.

My close relationship with my grandparents has guided me through life's ups and downs, ultimately influencing my decision to become a physician. However, my journey in the field has revealed a pressing need to redefine our approach to care for the elderly. This is especially critical given the anticipated expansion of the elderly population in the U.S. from 56 million to a staggering 80.8 million in 2040. Encouragingly, I've encountered mentors and fellow physicians-in-training who share my vision for elderly care, leaving me optimistic for the future. I firmly believe that by harnessing the unique strengths of both younger and older individuals, we can foster innovation, mentorship, and better health care for the elderly. In doing so, we can illuminate a path toward a brighter future in medicine, one where the wisdom of the elderly is cherished, much like the invaluable lessons I've gained from repeatedly dialing the familiar 10 digits of my grandparents' phone number.

What has your experience working with elderly patients been? Share in the comments.

Matthew is a fourth-year medical student at Drexel University College of Medicine. He aspires to be an academic anesthesiologist with particular interests in critical care medicine, cardiac anesthesia, geriatrics, and clinical research. Twitter: @MEKent97

Illustration by Diana Connolly