I had known Aparna for years. She was a jovial middle-aged woman, the phlebotomist who always drew my blood when I entered our local laboratory testing center. From middle school to high school to college, I felt a sense of ease upon seeing her familiar face in the clinical setting. Now I was sitting in the same gray seat once more, a few years post-college and a few years before entering medical school, with my left arm outstretched for venipuncture.

“Alright,” Aparna said as she deftly removed her needle and replaced it with a piece of gauze. “You’re all set!”

I looked down at the bandage that now covered by cubital fossa. “Thank you,” I replied.

“You’re welcome. How is your grandfather doing?”

Aparna knew my grandfather well, having drawn his blood on multiple occasions for more than a decade. Now she was following my grandfather’s progress from afar over the past several months — from his admission to the hospital, to his entry to rehab, to, finally, his return back home.

“He’s doing much better,” I said. My grandfather’s condition had improved tremendously, but in the process, my family had dropped everything to care for him at home. Our collective lives had been thrown into chaos since his illness, and now every day presented a different challenge. I hadn’t seen or spoken to my friends in months. The experience was isolating, I admitted, an experience that my family and I had never been expecting.

Aparna nodded. Her voice quavered as she spoke. “When something like this happens, everyone disappears. People you thought you knew, your friends … Even doctors can do nothing except come and go. In these situations, only family pulls through. Only family.”

Family, she said, bore the brunt of care. They were the true caregivers.

Today, more than 1 in 5 Americans represent family caregivers. According to a May 2020 report from the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, an estimated 41.8 million adults in the U.S. currently provide care for an adult over the age of 50 — an increase of 2.5% from 2015. Caregiving itself spans all demographics, including racial/ethnic group, income or educational level, work status, age, sexual orientation, and gender identity. And caregivers themselves can be just as diverse, consisting of either “families of kin or families of choice.”

Regardless of family structure, the work of caregiving can be excruciating. Caregivers are responsible for things that many of us take for granted — namely, activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). The practical assistance that family caregivers provide is integral to the lives of their respective care recipients, especially when those care recipients are unable to properly care for themselves. Basic activities such as ambulating, cleaning, bathing, showering, preparing meals, eating, general housework, and more need to be effectively managed on a daily basis.

The duties of a caregiver, however, extend far beyond traditional ADLs and IADLs. Indeed, caregivers are often vital to the clinical encounter: not only can they act as the care recipient’s advocate, but caregivers can also oversee and perform medical/nursing tasks themselves. Approximately 65% of caregivers, for example, directly communicate with health care professionals about their recipient’s care, while 58% perform more complex care responsibilities such as delivering injections, monitoring vitals, operating equipment, and more.

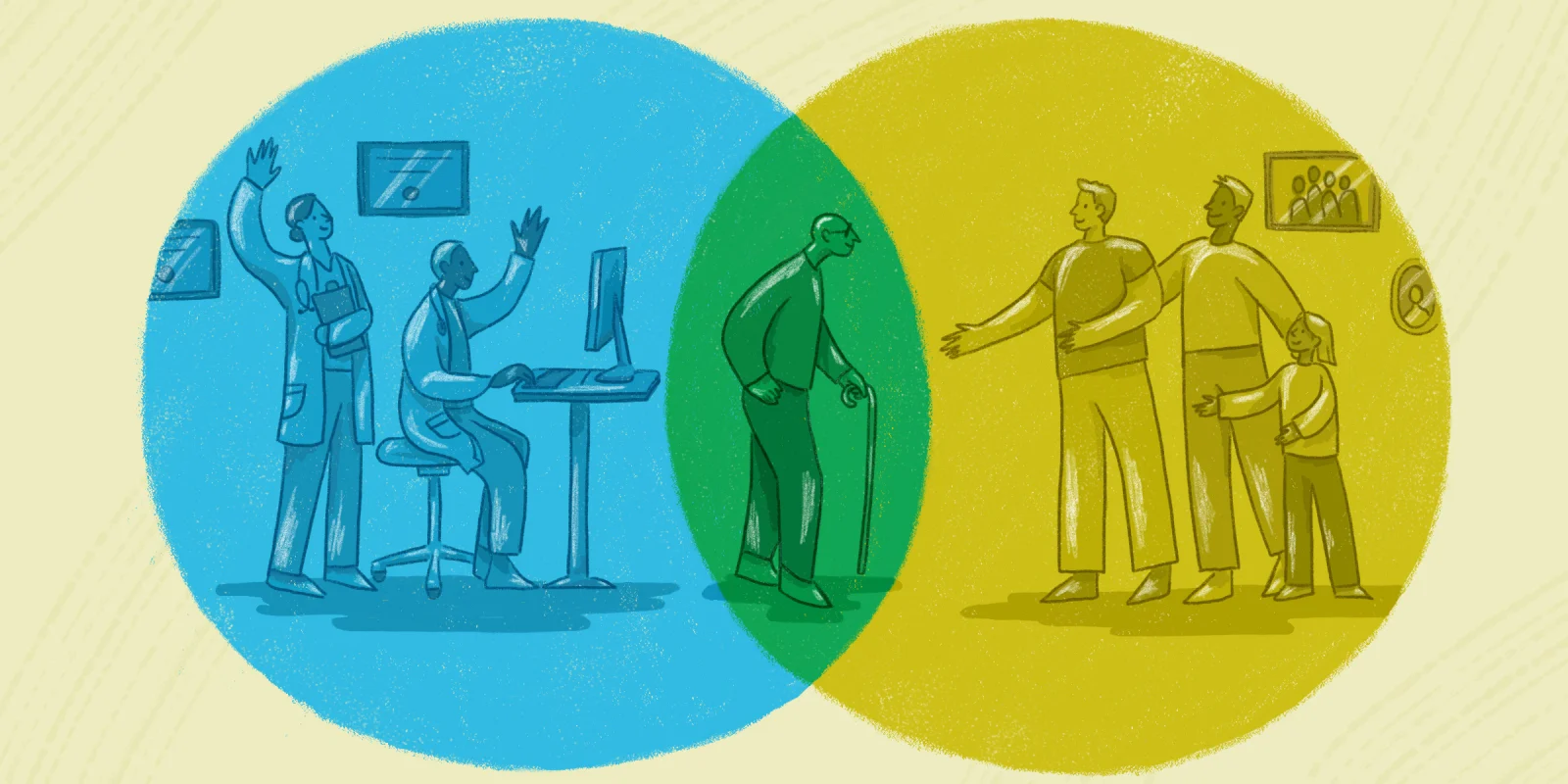

In some ways, then, the role of the caregiver parallels that of the physician. Both work in service of someone who needs help due to physical illness or cognitive decline. Both are also more susceptible to developing adverse health effects, including chronic stress, depression, and burnout. The ongoing pandemic has only further increased the strain that physicians and caregivers have always carried, navigating the realm of health care side by side. These two identities share much in common — and yet, the two are also nothing alike.

Not all caregivers are physicians, but are all physicians caregivers? Many appear to think so. Various reports published during the COVID-19 era describe physicians as caregivers, so much so that the distinctions between the two roles have blurred. Both Time magazine and the American Medical Association, for example, recently advocated for the well-being of front-line health care workers under the headlines of “caring for our caregivers.” The implication here is that physicians are de facto caregivers — a framing that shapes doctors’ own self-concept as well.

I cannot help but fear that this sort of language generates a false equivalence. The work of doctoring, after all, is fundamentally different from the work of caregiving. If physicians are responsible for diagnosing, treating, and managing illness, then caregivers are responsible for something just as significant yet frequently underrecognized: the direct and daily care of a loved one outside the clinical space. Other professionals agree that a clear distinction must be made between the identity of the physician and the identity of the caregiver. “I resent being referred to as anything other than a doctor…” Dr. C. Richard Conti insists. “[A]nd I hope my patients will never refer to me as a caregiver or provider.”

Conti’s comments might come across as shocking, even antithetical, to physicians who view medicine as their personal vocation. His words offer a different interpretation of the physician role, one that is distanced from caregiving via a framework of professional hierarchy. Indeed, Conti goes even further by insinuating that the caregiver role is beneath physicians — and thus beneath the practice of medicine.

I agree with Conti that caregiving and doctoring are not the same, but not because of the reasons he describes. I believe that physicians and caregivers are united in their proximity to lived suffering — and although both work in service of the patient, that does not necessarily mean that the two are synonymous. In fact, the two can sometimes be in conflict with one another. Both roles are integral to the clinical encounter, but to say that they are the same obscures as well as detracts from the work that caregivers perform. Doctors are often trained to view themselves as caregivers and the practice of clinical medicine as caregiving, but what if that perspective is flawed? As physician-anthropologist Dr. Arthur Kleinman proposes, perhaps modern medicine itself fails to meet the standard of caregiving. Such is the paradox of the profession: “[M]edicine invests little in caregiving,” Kleinman writes, “yet it is core to health professionals’ motivations and identity.”

As I near the end of my preclinical training, I marvel at just how much I have gained in the past two years: a stethoscope, a white coat, a depth of privileged knowledge — all markers that will contribute to my identity as a future physician. But I also recall the long-gone days I spent tending to my grandfather at home, the perseverance with which my family and I navigated the health care system, the joy and pain that came from being in his presence. We were caregivers — an identity that I still carry with me even though the work is finished, an identity that is separate from my role as a physician-in-training. Maybe caregiving itself is beyond the purview of doctorhood. Indeed, in its ideal form, caregiving is what Kleinman calls a “moral experience,” an exchange that is “closer to gift giving and receiving among people whose relationships really matter.”

The work I did with and for my grandfather, I know, is not the same work I will do in the future as a physician. As Aparna reminded me years ago before I even stepped foot into medical school, the physician has many different faces: diagnostician, detective, teacher, healer. Caregiver is not one of them.

Do you think doctors should be called caregivers? Why or why not?

Saljooq Asif, MS is a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine. He is also a Lecturer in the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, where his scholarship focuses on the broader health humanities in relation to narrative ethics, racial justice, popular culture, and more. He is a 2021-2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect privacy.

Illustration by Diana Connolly