Amidst all the social changes and health policies enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the way in which physicians can care for their patients has taken a turn as well. Discussed for years as a means of convenience by circumventing travel, being more time-efficient, providing wider access to specialty physicians, and reducing overhead costs, telemedicine has now temporarily replaced face-to-face visits. It has taken center stage by being the standard of care for which physicians can triage and treat their patients. In all pragmatism, it was the right time to put this practice into full effect as it virtually (pun intended) allows everyone to avoid close personal contact and practice social distancing with the ultimate goal of reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Since I have only heard about telemedicine, I was excited to try it out for the first time. Being in residency training, it was an unfamiliar concept as I was always taught that medical learning was best when at the bedside of the patient. And even though telemedicine was a necessity rather than a convenience during this time, I wondered how Sir William Osler would have commented on this practice, as he was a steward of the physical exam. Although many physicians are less dependent on the physical exam these days, at times it can make a difference in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient. With telemedicine, I couldn’t have it as part of my medical armamentarium. Would Osler have even let me present a patient to him had I not done the physical exam?

Despite that, I felt Osler would not entirely shun me. One of his most famous adages, “Listen to your patient; he is telling you the diagnosis,” stuck out to me with the use of telemedicine. It was now more important than ever to get a thorough and clear history when talking to my patients in order to ensure I could accurately address their ailments. With the higher potential for misdiagnosis, I had to solely rely on a careful history-taking in order to assess the most imperative differential every physician should address: sick or not sick.

As for the sacred bond between physician and patient, would Osler have felt it compromised? The advantages of a face-to-face interaction allows for the therapeutic value of physical touch and for assessing the nuances of body language to help with diagnosis and to build rapport. Lacking the power of the healing touch, telemedicine allowed me to rely on my sense of hearing and speech in order to connect with my patient and still provide high-value care.

I remember distinctly a phone visit I had with one of my patients during the first few days I used telemedicine during the pandemic. She had previously seen my colleague in clinic for the first time a month prior and was diagnosed with postpartum unipolar depression. She had recently had her second child and overwhelmingly developed all of the symptoms to meet depression afterward. The plan was to trial her on an SSRI that was safe to use while breastfeeding. As I called her and said my perfunctory introductions and explained how the clinic was converting all visits to telephone encounters given the COVID-19 pandemic, I began to ask how she was doing. She said she wasn’t feeling that much better. And as I started to broach further and quantify her symptoms, I could already hear she wasn’t doing well. The change in her tone, the pauses and cadence in her speech, and the quivering of her voice allowed me to recognize she had started crying, despite never laying eyes on her. In the clinic, most physicians would have offered her a Kleenex and held her hand as they displayed compassion in their facial expression. But on the phone, I could only comfort her with my words, and so I firmly stated “It’s OK. I’m here. I’m here.” I kept quiet to allow her to speak freely. She then let me know that she was still feeling sad all the time; guilty for how she felt and thoughts of inadequacy as a mother; agitated with her husband; and depleted as she did not have the same energy, focus, or appetite. Although the healing touch was not available, I used my words to convey compassion, commiseration, and sadness. I wanted her to know her suffering was acknowledged and that her doctor was present in the given moment to share these fears with her, even if we were not across the room from each other. After ensuring there were no emergent concerns, including thoughts of harm, suicide, or homicide; imminent danger to her children; or inability to adequately maintain social and occupational function, the patient was elated to hear that she would be referred to cognitive behavioral therapy (via weekly telephone sessions during the pandemic). With therapy and titration to therapeutic dose of her SSRI, she and I would have another encounter again in a few weeks to monitor her progress.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the livelihood and health of billions across the world. It has changed all aspects of daily life for months to come. Moreover, it has shifted the standard in how we can continue to care for our patients. Through it all, people have been resilient and have adapted. During this pandemic, it is more important than ever for physicians to still “see” their patients and make sure they get the adequate medical attention they need. We must remain available to assuage their concerns in these uncertain times. Afflictions and illness will continue to affect our patients’ lives even though the rest of the world seems to be on hiatus.

Although telemedicine is a different clinical practice model, it still provides physicians a chance to provide high-quality and high-value care if we remain vigilant about it. As for Osler, of whose sentiments I still wonder about, another one of his aphorisms come to mind: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” Because despite not being able to be at the bedside, if I do it right, perhaps I can still maintain and cultivate the personal and intimate bond that is to be expected between a doctor and his patients. Neither the art nor the science of medicine would be lost.

Nghia Pham is an intern physician training in the state of California. He is interested in high-value care, health-care delivery systems and medical humanities. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.

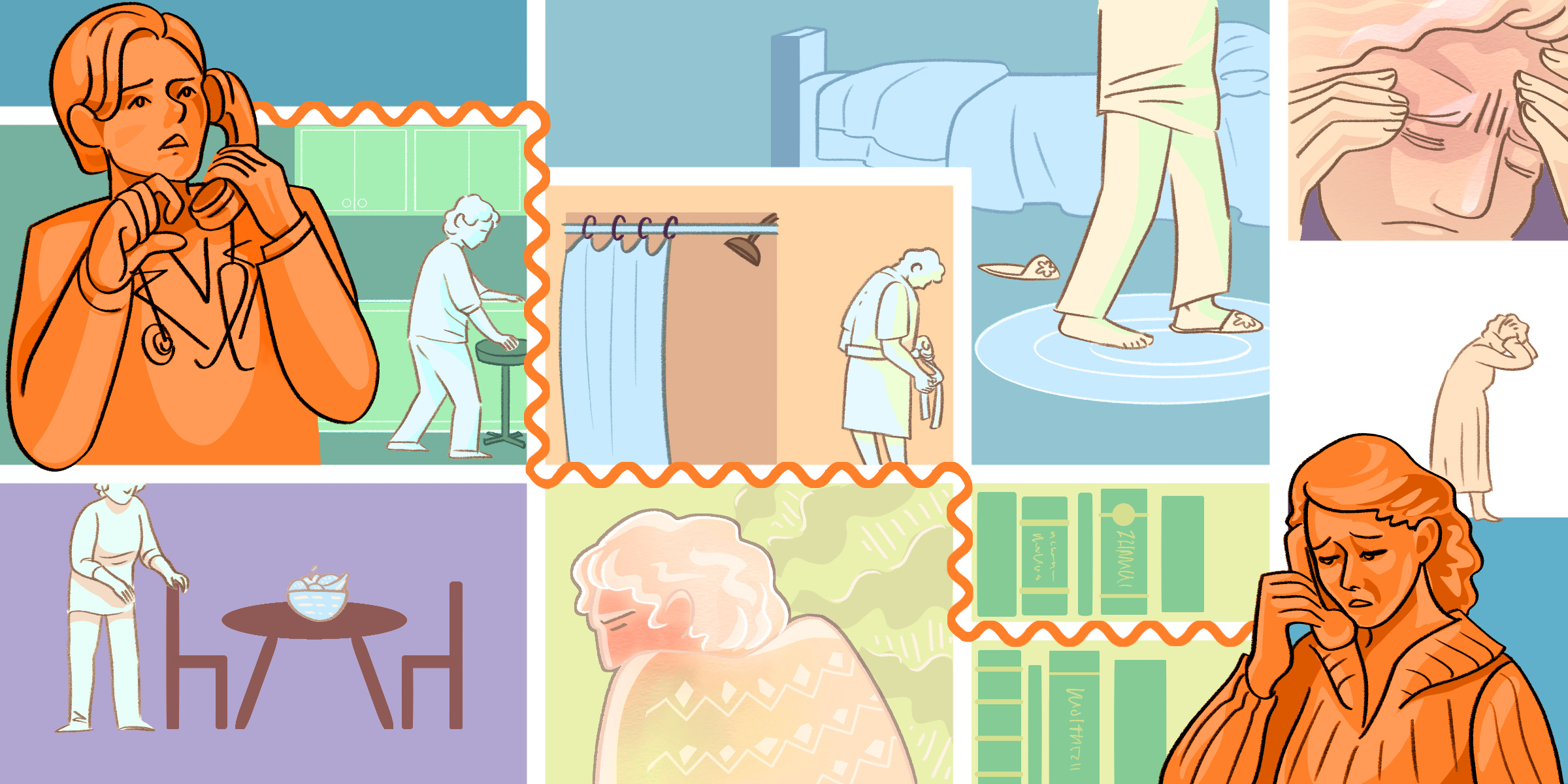

Illustration by April Brust