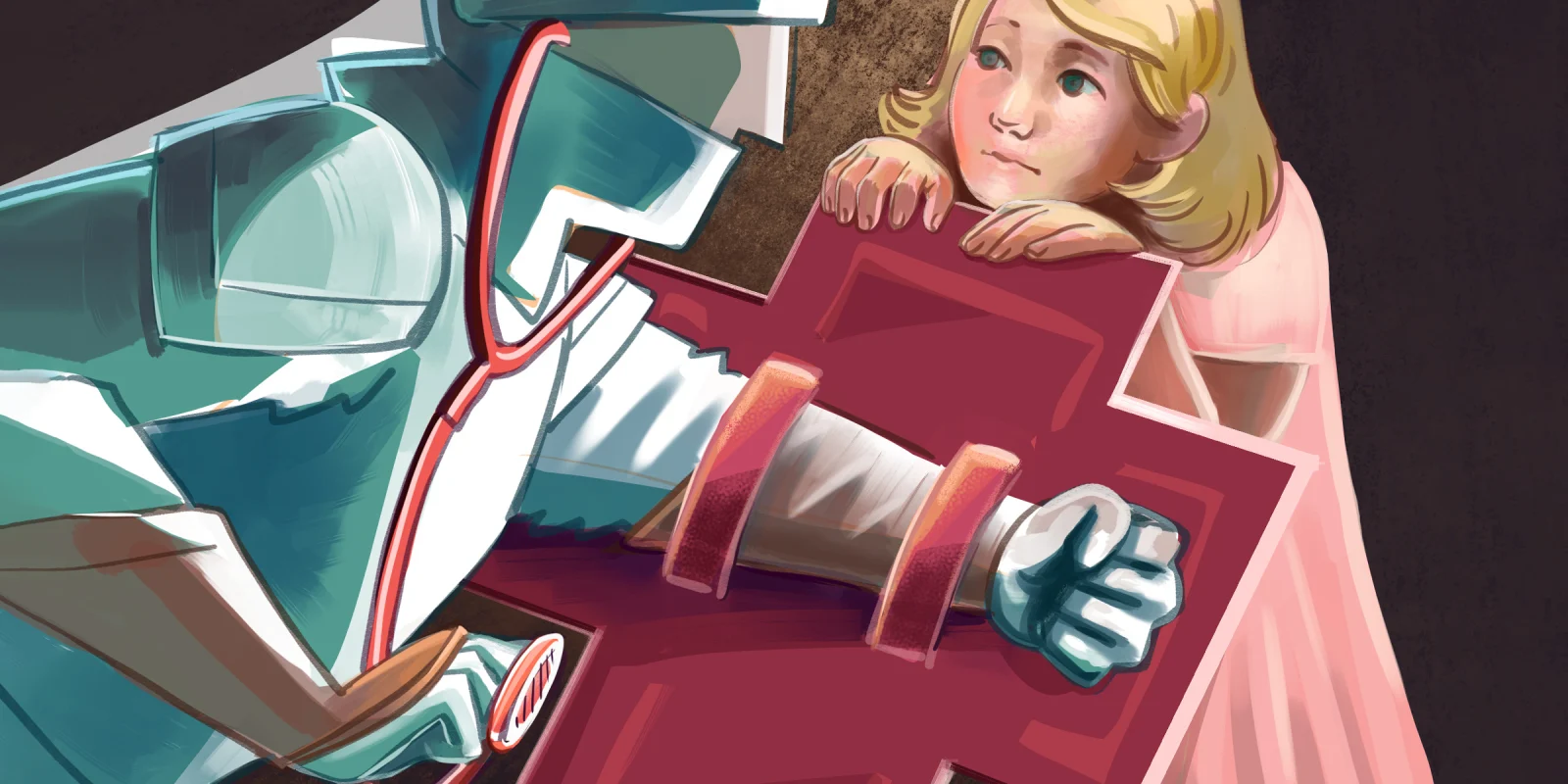

On a recent drive in to work, I was drawn in by a radio program describing trends in hospital marketing. The host of the show enthused about an ad campaign at a pediatric hospital and how it was a boon for the hospital, helping them achieve a lofty fundraising goal and boosting their number of donors. The ad campaign was notable in that it shifted from conventional medical advertising, with its heavy appeals to pity and empathy, to utilizing iconography commonly seen in sports marketing. Sitting in the parking lot, I immediately pulled up the ad. Upbeat hip-hop music blared in the background, while pediatric patients donned boxing gloves, smeared black eye makeup on their faces, and huddled together. I was moved by the ad, and after watching, it was clear why this marketing campaign resulted in a reported “29% increase” in the number of hospital donors. The iconography of sports is aspirational, empowering. However, one component I was struck by was a set of images commonly used in the sports world: those of war. In between the scenes of hospital workers putting on headlights and PPE, soldiers don armor and raise swords. A child enters the OR in boxing shorts, followed by soldiers surveying the scene for battle. One of the final images in the ad is a group of soldiers charging into battle, with a pediatric patient sprinting ahead in the charge.

Health care is replete with metaphors of a war. While it’s one thing to visually see a child standing shoulder to shoulder with a group of armored swordsmen, the verbal equivalent is commonplace. We listen to patients describe themselves as fighters following a cancer diagnosis and read articles describing the health care community as “front line” workers. These phrases are so ubiquitous that we often may not even stop to consider their implications.

Nowhere is this type of language more common than in the world of oncology. When patients are faced with the life-altering news of a cancer diagnosis and the grueling reality of cancer treatment, we attempt to prepare them for the months and years ahead. In calling someone a fighter, the hope is to empower them during a profound loss of agency. By utilizing the language of battle, we help our patients take back control and become more active agents in their own care. However, many studies have found that this language often can have the opposite effect. Though this imagery may make complicated treatment regimens more understandable, patients have found use of war metaphors to lead to more fatalistic views of cancer and make treatment appear more difficult. Another major downsides of utilizing this type of language is that it can overemphasize the willpower of the patient in their wellness. In suggesting that someone is a fighter, we may overemphasize patient effort in the treatment process. Many patients have untreatable diseases or choose to prioritize comfort over cure, and their death is not the result of lack of effort or “fighting” strength on their part.

Beyond the realm of patients, bellicose imagery can be seen in the realm of clinicians, particularly in the era of COVID-19. In the early days of the pandemic, health care workers were described as “heroes,” selflessly serving on the “front lines” of the war against COVID, donning PPE as if it were armor. This language helped to create solidarity among workers during an unprecedented time, and to foster appreciation for the difficulties of the job. However, this bellicose language similarly comes with unintended consequences. By describing health care workers as soldiers, it is implied that suboptimal working conditions may simply be part of the job, what we signed up for. By painting the physician as a hero, the very real risk of mortality that was unveiled during COVID-19 became not just an option, but an expectation.

The use of metaphor in health care is a powerful tool. It can take seemingly incomprehensible topics and distill them into something understandable. Metaphors can build unity and help create meaning. However, we must remember that for all the benefits they may have, there are downsides as well. Apropos of the discussion above, metaphors in health care can be a double-edged sword.

Do you use metaphors in your practice? Why or why not? Share in the comments.

Marc Drake is a fifth-year resident in the Department of Otolaryngology and Communication Sciences at the Medical College of Wisconsin. His clinical interests include facial reconstruction, violence prevention, and the interplay between urban design and health care. Dr. Drake is a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust