Around the operating table, the attendings and fellow loomed imposingly like redwood trees: marked by legacy, steady, unmoved. Even in their stillness, it was clear that something felt unusual to them, too. The scrub nurse, breaking the silence, named the offending anomaly: “Wow, this is weird. Everybody in here is a guy.”

My attending looked around at his towering counterparts, chuckled, and stated plainly, “As it should be.” His smile did not fade as he looked down toward me, already small, out of view, and now feeling increasingly unsteady on my fledgling feet. “Don’t tell your dean I said that,” he said.

As a Black and Latina woman, I am always a minority in medicine. There, as a subintern, I suddenly became aware that I was also in the minority. The realization was at first shocking — that my presence wasn’t significant enough to keep such words from being said aloud. And then it was hurtful: Did they really think that I didn’t belong there, with them, the surgeons? Then it was confusing: Shouldn’t I feel lucky to have made it so far in medical school without hearing a comment like this one? Finally, it was unsettling, because the attending’s concern as he reflected on his comment was not about the remark, but rather on the repercussions of my dean finding out about it.

This concern about the impact of our words is common in the modern hospital, expressed in statements like, “Everyone is just so sensitive these days” or “You just can’t say anything anymore.” As the trainee workforce has become increasingly diverse, people have been less likely to utter sexist, racist, xenophobic, homophobic, and other divisive statements. But behind the silence, these sentiments thrive like weeds: inconspicuous, uninhibited, and insidiously suffocating to our growth as individuals and institutions.

“Don’t tell your dean” reflects an understanding we have come to accept as a medical community: It’s OK to think those things, just not OK to say them. I worry that modern medicine, like the world around it, is conflating this political correctness with progress. And I worry even more about its potential consequences: a culture in which the physicians responsible for the care of diverse patients and for the development of diverse trainees are more worried about being called out for sexism or racism than they are of actually being sexist or racist.

Since the time I first came face to face with this culture in the OR, not much has changed. Earlier this year, JAMA released a podcast on structural racism that was, unintentionally, itself a manifestation of structural racism. Twitter’s medical community and even mainstream media reacted with heavy backlash that a high impact journal could have approved such egregious claims, calling for the resignation of the journal’s editors.

“Don’t tell your dean,” like the response to the JAMA podcast, is a product of a pervasive cancel culture. “Cancel culture” is a form of vigilante justice that comes down swiftly in response to a misstep in word or deed, deemed unacceptable by the elusive “they,” that ultimately results in one’s public cancellation. In medicine, we have fed the idol of cancel culture and now find that it stands directly in our path toward inclusion, belonging, and hospitality in our hospitals.

Why? Because in order to safely promote growth toward justice, we should treat errors with edification, not exile, in the same way that a typical trainee’s learning environment allows for mistakes. Though fear of public shaming from cancel culture might make most practitioners less likely to say “as it should be” or to issue apologies for a podcast’s language, it has not engendered progress toward dismantling the beliefs that underlie those words.

As an alternative to cancellation, I would love to see medicine adopt another practice: confession. Morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences offer an example of a medical tradition built on gathering and confessing. The conferences provide a structured opportunity for practitioners to give voice to error, with the assumption that the error will be forgiven. Done well, both M&M conferences and confession rest on a foundation of honest authenticity, humble imperfection, and a spirit of wisdom over mere knowledge.

Implementing an approach like confession requires that we come as we are rather than keep quiet the parts of us that we worry could be judged. In this profession, with the intimacy of the patient-practitioner relationship, there is seemingly no way to be one person at home and another at work. If someone is implicitly (or explicitly) racist at home, so too will they be at the hospital. For communities at the margins especially, these biases hold great weight.

Learning from our mistakes requires that we acknowledge the real harm that they have caused; intent does not equal impact. Just as minimizing the effect of a medication misadministration or displacing responsibility for a technical error breeds risk for harm in the future, making light of injustice perpetuates and empowers it. Finally, as is the case for M&M conferences, the practice of confession is not meant to be a one-off retreat. It is meant to cultivate the habit of being constantly formed and re-formed. Professor Loretta J. Ross has codified “calling in” as a framework for growth. Calling in, she says, is a conversation had with compassion that neither ignores nor inflates the damage done; it is a “a call out done with love.” If cancellation calls out, demands retribution, and ends the story, then confession calls in, begins a new chapter, and invites reform.

At the end of it all, I didn’t tell my dean. Partially because I was a medical student, and because the reality of hierarchy weighed on me. But mostly because I knew that, even if my attending hadn’t uttered his statement aloud, the sentiment would have been loud and clear. Many of you have probably been like my attending; I have been like my attending. And though I didn’t tell my dean then, I’m telling you now. In doing so I’d like to think that, rather than canceling anyone, I am inviting us to realize that we can all become the kind of surgeon whose ORs are a place where everyone belongs. As it should be.

How do you believe medicine can move toward more equity? Share your thoughts in the comment section.

Danielle is a general surgery resident at Massachusetts General Hospital and an alumna of the Theology, Medicine, and Culture fellowship at Duke Divinity School. She plans to pursue pediatric surgery with emphases on palliative care and progressing surgical equity globally, and is passionate about cultivating space for practitioners to be who they are and belong where they are as both people and professionals.

Follow her on twitter or instagram: @daniellis__.

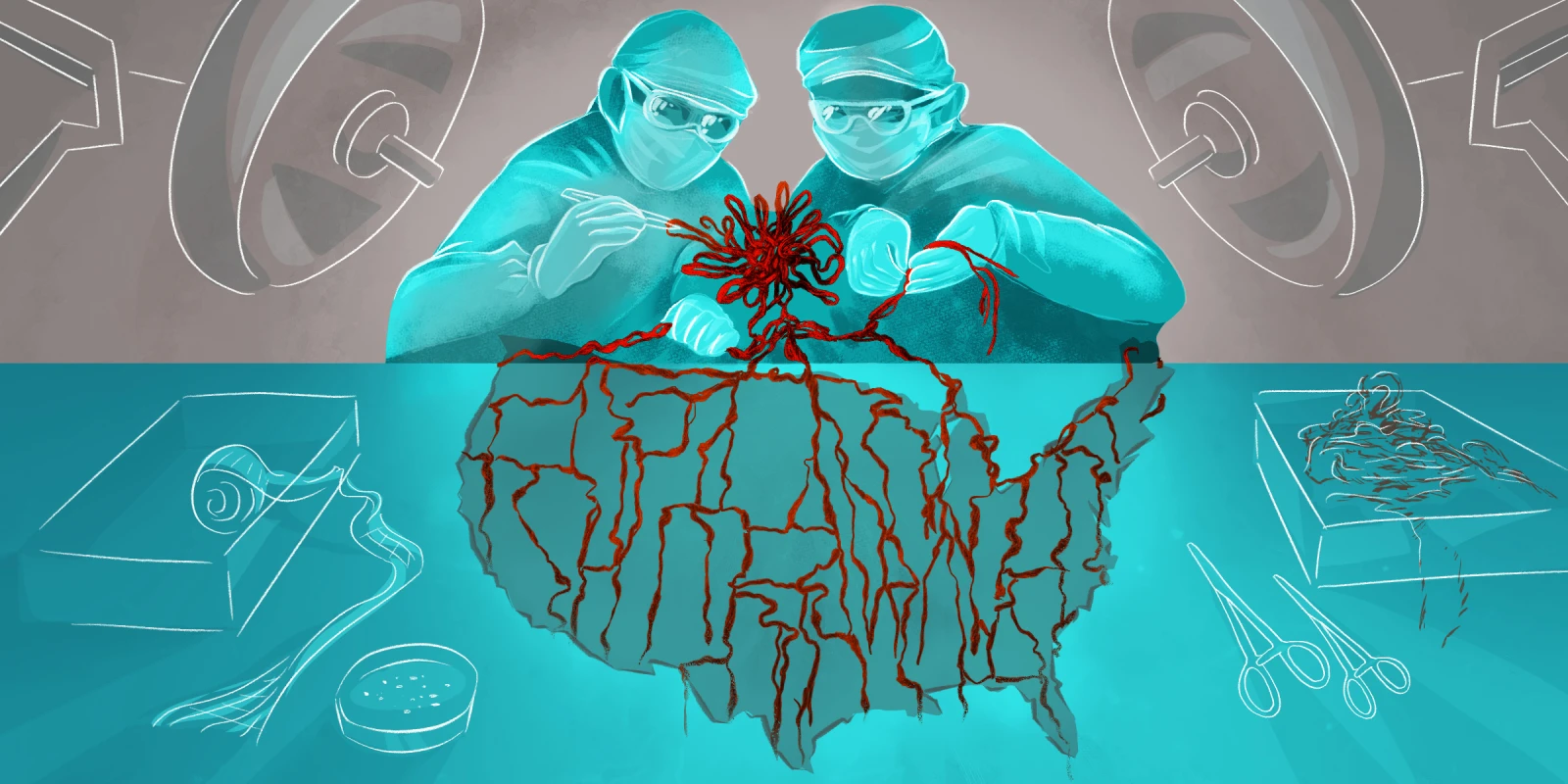

Illustration by April Brust