I entered the ED bay to meet Mrs. P, and as I drew back the curtain, I was immediately struck by her appearance — she was completely yellow. Her jaundice was so pronounced that it was hard to focus on anything else, even our introductions. Mrs. P was a seemingly healthy 65-year-old who had come to the hospital with a few weeks of progressively worsening jaundice. While she had been experiencing some fatigue and nausea, she was otherwise healthy and feeling well.

As Mrs. P and her husband shared her history, I learned that she had recently started a new weight-loss supplement. A quick Google search revealed that some of its ingredients were known to potentially cause drug-induced hepatitis. I thought, “That’s gotta be it.” Or perhaps it was something more mechanical, like a stone. Mrs. P didn’t seem concerned, my residents didn’t seem overly worried, and honestly, I didn’t feel particularly anxious either.

We decided to proceed with imaging to better evaluate her liver and assess the potential presence of a stone, in addition to ordering some blood work. After ensuring she was settled for the night, I left for the day. The next morning, as I was pre-rounding, I noticed that her imaging results hadn’t been released yet. I prepared my presentations for rounds, and we made our way to the ED to meet with Mrs. P as a team.

Just moments before entering her room, my resident stopped the group. “Her scan results just came back,” she said, and the expression on her face immediately sent a wave of unease through me. “There’s a mass at the pancreatic head, highly suspicious for malignancy.” Everyone seemed stunned by this news, even our attending. When we had spoken to Mrs. P the day prior, pancreatic cancer hadn’t really even been on our minds.

Before medical school, I spent five years working in clinical oncology research, which exposed me to many difficult conversations surrounding cancer diagnoses and prognoses. My team was aware of my background and my interest in pursuing a career in oncology. So, when we learned of Mrs. P’s diagnosis, my resident turned to me and asked, “Would you be interested in and comfortable breaking the news?” She reassured me that the team would be right there, ready to step in if I needed support.

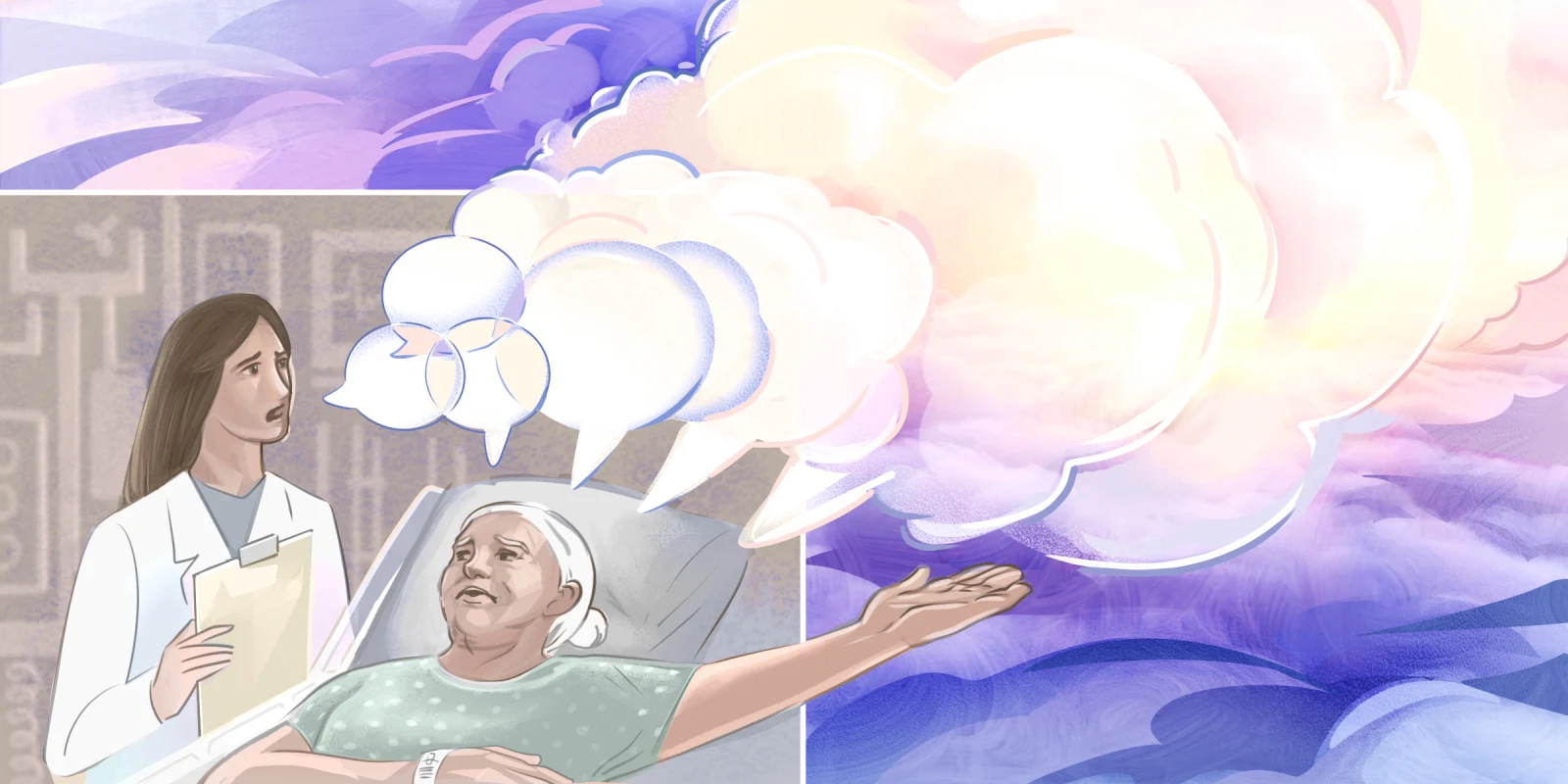

I was honored that my team had confidence in me to lead such a pivotal conversation. However, the responsibility didn’t come without anxiety. I had never broken news on my own before; I had only ever practiced in a classroom setting. I remember feeling a knot in my stomach, worried that my voice might crack or that I might become overwhelmed with emotion if she started to cry.

We slowly entered her room, and I knelt beside the bed so that we could be eye level. I said, “Mrs. P, we have some hard news to share with you this morning. Your scan is worrisome. Would you like us to wait to share more until your husband arrives?”

She said, “Yes … please wait,” quickly followed by an anxious, “OK, no, just tell me!”

I said, “I wish I had better news. Your scan is showing a mass in your pancreas, and we are worried that it could be cancer.”

She paused for what felt like minutes, her eyes became full of tears, and the only words that she managed to mutter were, “Oh, shit.”

She grabbed my hand, and at this point, the other residents were also kneeling beside her bed. We had all put our hands on top of Mrs. P’s. The emotion filling the room was palpable.

I realized just how uncomfortable silence can be, particularly when faced with something as devastating as a cancer diagnosis. I felt an overwhelming urge to say something — anything — to break the silence, but I refrained. I wanted to repeat “I’m sorry” over and over, but I knew that wouldn’t bring the comfort she needed. Instead, I chose to simply be with her, hold her hand, and embrace the silence.

After a long pause, Mrs. P finally spoke. “This is so hard for me to hear,” she said, her voice trembling. “My mom died of pancreatic cancer, and watching her go through it almost broke me.”

She then asked us to call her sister in Boston and deliver the news, explaining that she didn’t have the strength to share it with her, especially since her sister had been deeply affected by their mother’s battle with cancer.

We put the call on speakerphone, and I introduced myself before slowly sharing the details of Mrs. P’s hospitalization. As her sister processed the news, they both began to cry together over the phone. Her sister immediately began making plans to fly to North Carolina.

Through her tears, Mrs. P turned toward the phone and sobbed, “I really need Mom. I need a hug from her so much right now.”

In that moment, my eyes also welled with tears. It was a profound and heartbreaking experience — hearing a 65-year-old woman cry for her mother in the midst of her own suffering. This is a moment in my medical career that I will never forget. One that reminded me of the deep, human connections we witness in medicine, and the incredible privilege that we as medical students have in being involved so intimately in the most vulnerable parts of patients’ lives.

How do you prepare to give patients bad news? Share in the comments.

Rachel Lile-King is a fourth-year medical student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with five years of clinical research experience in gynecologic oncology. She is applying to internal medicine with the intention of pursuing a career in medical oncology, driven by a deep interest in cancer therapeutics and the profound impact of patients whose experiences have shaped her commitment to the field.

Disclaimer: All names and ages have been changed for privacy.

Illustration by April Brust