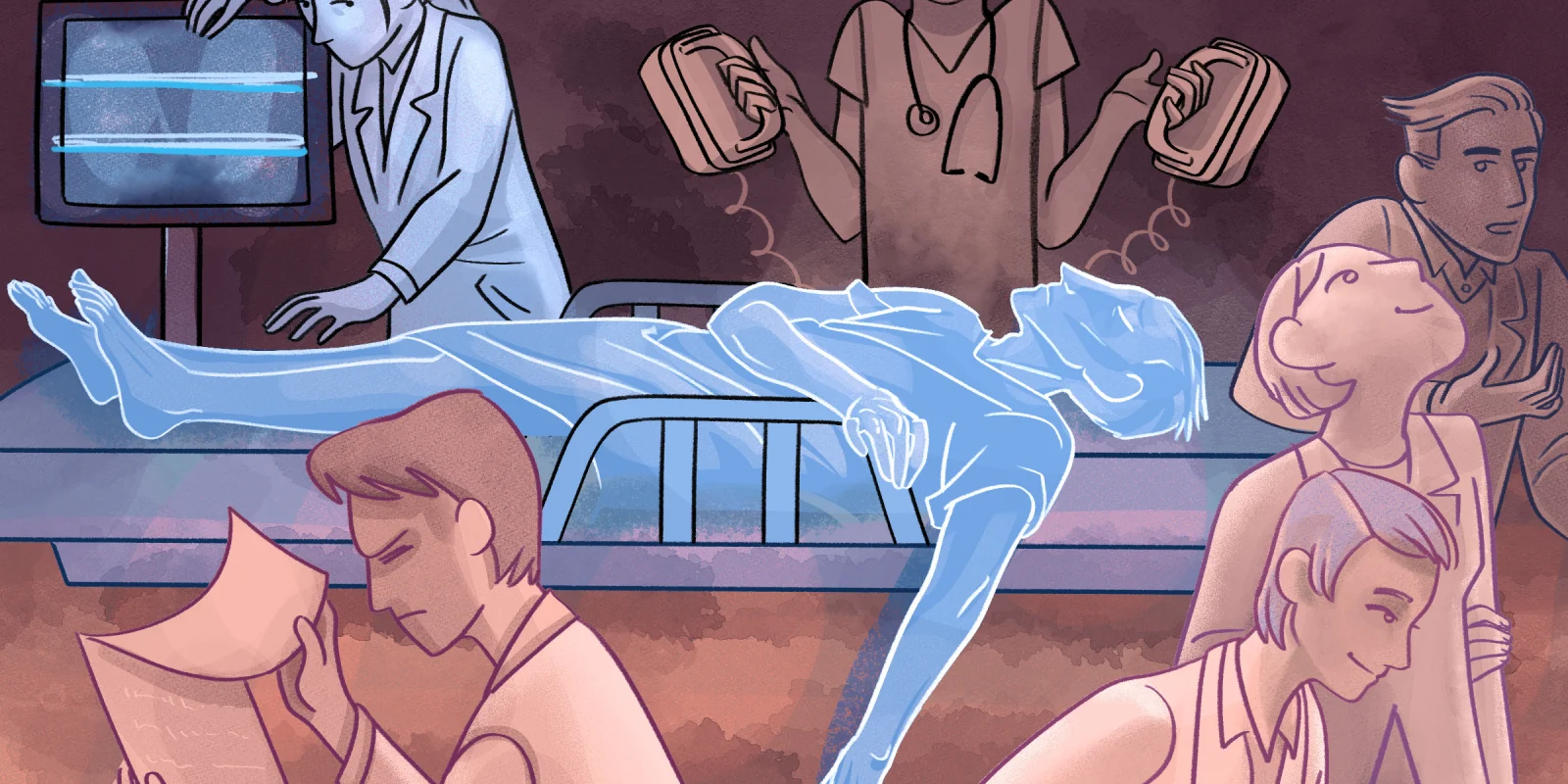

In medical school, the clerkship years can often feel like just a whirlwind of “firsts.” Your first time seeing a patient on your own. Your first time writing a note in the EMR. Your first time delivering a baby. By mid-April of my third year, I’d steadily hit every expected developmental milestone of my budding clinical journey, but had yet to encounter the real first in medicine: the death of a patient. Every story painted the same picture: how it changes you, how you never forget it, how you replay the moment over and over in your head as you struggle to comprehend the fleetingness of life and your (ultimately futile) role in extending it. As I began my trauma surgery rotation, I had a somber feeling that while I had escaped it for so long, my first foray with death would likely come that week. I was right.

In medical school, the clerkship years can often feel like just a whirlwind of “firsts.” Your first time seeing a patient on your own. Your first time writing a note in the EMR. Your first time delivering a baby. By mid-April of my third year, I’d steadily hit every expected developmental milestone of my budding clinical journey, but had yet to encounter the real first in medicine: the death of a patient. Every story painted the same picture: how it changes you, how you never forget it, how you replay the moment over and over in your head as you struggle to comprehend the fleetingness of life and your (ultimately futile) role in extending it. As I began my trauma surgery rotation, I had a somber feeling that while I had escaped it for so long, my first foray with death would likely come that week. I was right.

It was a slow morning in the trauma bay. I anxiously sat in the resident room, making bullet markers out of masking tape and paperclips, staring at my pager in hope of something exciting. “It’s brutal, but incredible,” my classmates had said of this rotation site, a Level I Trauma Center in Chicago. As a student torn between the fierce intensity of trauma surgery and the case variety of EM, I couldn’t think of a better place to help guide my decision. But in order to do so, I needed to see some cases.

My residents told me to go grab some coffee while it was still slow. As I stood in line, deciding if I needed a venti or grande caffeine boost this morning, I felt the pager at my waist vibrate and chirp: “32 YO M GSW HEAD.”

I ran to the ED, more excited about getting a page than I probably would be for the rest of my career. As I waited for the patient to arrive, I mentally reviewed the ABCDEs of trauma I had learned just the night before. The paramedics rushed into the trauma bay a few short minutes later, frantically wheeling in our patient. His face was unrecognizable, the entire upper half of his body camouflaged under a thick layer of dried and fresh blood. The paramedics recounted the history: a bystander had found him slumped over in the driver’s seat of his car with a gun in his hands, an apparent suicide attempt. The entirety of his lower jaw was mangled, faint moans escaping from what was left of his mouth. The attending and senior residents on the trauma team attempted rapid sequence intubation, while I attempted to simultaneously be helpful and out of the way. They soon tossed aside the laryngoscope in favor of doing a cricothyroidotomy, the rapidly pooling blood making adequate visualization impossible. I stood wide-eyed at the foot of the bed, coming to terms with the fact that the high acuity case I was oh-so-excited to see intersected with the worst day of someone’s life.

Moments later, the patient coded. We gathered in a line at the side of the bed for compressions. I thought about the harrowing series of events that would lead a man to this point, and how, if he survived, the journey ahead would likely be even more difficult. A nurse told me I was up next. I pressed my weight into the man’s chest, praying I was going both deep and fast enough. Unlike most experiences as a medical student just “going through the motions,” this was actually real — for these few moments, I was effectively acting as this man’s heart.

After several rounds of CPR, the attending called it: “Time of death 12:03.” As we all filed out of the room, I struggled with what to do next. Would I appear weak if I took a moment to process it? Would I appear heartless if I didn’t? The residents went about charting, and I excused myself to go change out of my now blood-soaked scrubs.

The experience stays vivid in my mind to this day, but in that moment, I didn’t feel very different. There was no surge of emotion that I struggled to keep bottled in throughout the day, nor any profound realization I had made about our mortality. The case was without a doubt tragic, but I found it difficult to truly grieve a man I knew nothing about, whose face I could never truly even see. A person had died in front of me for the first time in my life, and it felt like just another day on the job.

Was it because I didn’t have a more active role in saving the patient? If I were the one frantically attempting to insert an endotracheal tube through his neck, or the one who pronounced his death, would I feel any different? Were the residents and attendings more fazed than I was, only maintaining composure with hard-earned coping skills? Or was this the very nature of EM — an inadvertent blessing of never truly getting to know your patients?

My thoughts were interrupted by another page: “17 YO F MVA.”

Shivam Vedak is in his final year of the MD/MBA program at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is currently applying into Emergency Medicine. His professional interests lie in ED operations and leveraging data analytics to optimize delivery of care. He spends his free time training and performing in the Chicago improv comedy scene.

Illustration by April Brust