My reservation was for 9:00 a.m. I was shown to my seat at 10:10 a.m. When questioned at 9:45 a.m., the receptionist informed me only that the staff was running behind, her curt tone discouraging further questions. I would have walked out, but I’d been waiting too long for this popular establishment and even as a physician I was too intimidated to raise a fuss.

I was done after 10 minutes. Or rather, they were done with me. And despite my anticipation, I would have been serviced by an assistant had I not insisted on seeing the head of the establishment with his years of experience and training.

“Would you like to make your next reservation now?” The receptionist’s tone was more inviting than previous, as was her smile. I walked out, wondering if a tip jar on the counter might enhance attentiveness.

Would any of us have tolerated this out of a restaurant or any retail business? Of course not. The majority of us first-world consumers would have walked out indignantly in favor of other establishments offering better service for the same product. At the very least we would have summoned the manager for scolding, expecting better attention if not something off the bill. Except that episode was one of many similarly frustrating visits to a doctor. In response to voicing my frustration after several such appointments, the office manager reassured me she would look into it. Nothing changed on subsequent visits, nor did I receive a response.

So why do we allow this when our very health is at stake, but refuse to tolerate such indignity when it only means a ruined night out? Why must our compliance be taken for granted? Finally, why must we accept the literal impossibility of actually communicating with The Doctor himself or herself?

I admittedly have been part of the problem. In my first private practice group, I was safely shielded from the waiting masses by layers of receptionists, nurses, and a maze of hallways. I was enlightened not by patient complaints, but by the transition from physician to health care consumer. First with recurrent demoralizing encounters as the parent of a seriously ill child, then to doctor visits for my aging self. The experiences with my son in particular left me alienated and distrustful of my own profession.

I have, however, attempted to put such experiences into action, as opposed to simply harboring resentment. I first left the practice in favor of a solo endeavor. Next, realizing that metropolitan medical practice was becoming largely corporate, I continued to serve only rural clinics in need of specialist care. As an independent contractor, I attended these clinics free of obeisance to corporate industrialized medicine. In return for providing specialist services, I was allowed to structure my clinics with less quantity and greater quality of each patient encounter. Even with post-COVID staffing issues, such personalized acknowledgement of patient discomfort from all clinic staff has reduced frustration without extraordinary effort … or tip jars.

Lest this editorial be written off as self-righteous admonishment, it reflects an even greater degree of resentment likely felt by countless patients without access to the insider understanding of physicians. Real progress toward bridging the trust gap might be achieved if the medical establishment would lose its sense of omnipotence and act according to the laws of capitalism: acknowledge competition and earn consumers. Of course, competition in medicine may prove more theoretical than realistic. It is far easier to take one’s credit card and business to a different restaurant than it is to transfer medical records, insurance information, and all matter of test results to a different office. Never mind the not uncommon months-long wait for a new patient opening. Market competition is not a new concept; it has been advocated time and again regarding pricing and transparency in medical charges. Such concepts should be applied to patient relations, not just to patient finances. From front-line receptionists to physicians, all should bear in mind how they wished to be treated when they have been on the other side of the desk. A simplistic concept in theory, but in need of emphasis in practice.

To be clear, using standard business tactics in medicine should be done carefully. Earning patient confidence the way that businesses earn repeat customers is different than making all of medicine like the retail and business industry. The surrender of physicians to large health care corporations or hospital-based practices has brought production-line care to an uncomfortable forefront. With cost-cutting measures, including a focus on quantity of patient visits at the expense of quality time spent, even minor transgressions of time are compounded down the line. Gridlock extends to the waiting room, where one is tempted to finally say “Check please!” instead of terminally waiting to be called.

My current practice without constraints of time per patient or number of patient encounters has meant fewer patients and thus reduced income, but has led to greater satisfaction by clinician and patient alike. My waiting room is not a waiting room; it is more a greeting room, staffed by team members genuinely cognizant of the influence they have on encounter satisfaction regardless of medical issue or outcome. We’re all minding the store.

I recognize that my journey is not applicable to many practitioners who can’t abandon well-ensconced offices and assured salaries for distant clinics, solo management, and reduced income. One size doesn’t fit all; other physicians have come forth with epiphanies born from their own experience as patients, but they too admit a general solution is elusive. Surgeons must negotiate different responsibilities than pulmonologists; psychiatrists’ schedules differ from time and patient responsibilities of pediatricians, as only two of many examples.

Difficult, however, doesn’t mean impossible. Small initial steps and even financial sacrifice toward practicing medicine with reciprocal respect between clinicians and patients, beyond written or legislated mandates and guidelines, should be possible even in “bigger stores.” Naive and simplistic? Hopefully not. At least in my own practice, I haven’t had to reach for the tip jar yet.

What are your thoughts on a "tip jar" in medicine? Share your thoughts on improving clinic visits in the comments.

Scott Eveloff MD is a practicing pulmonologist and sleep disorders physician serving far-flung clinics in a rural Missouri hospital. Having dealt with both professional and personal medical circumstances, he is interested in ethical, business, and medical issues on both sides of the white coat.

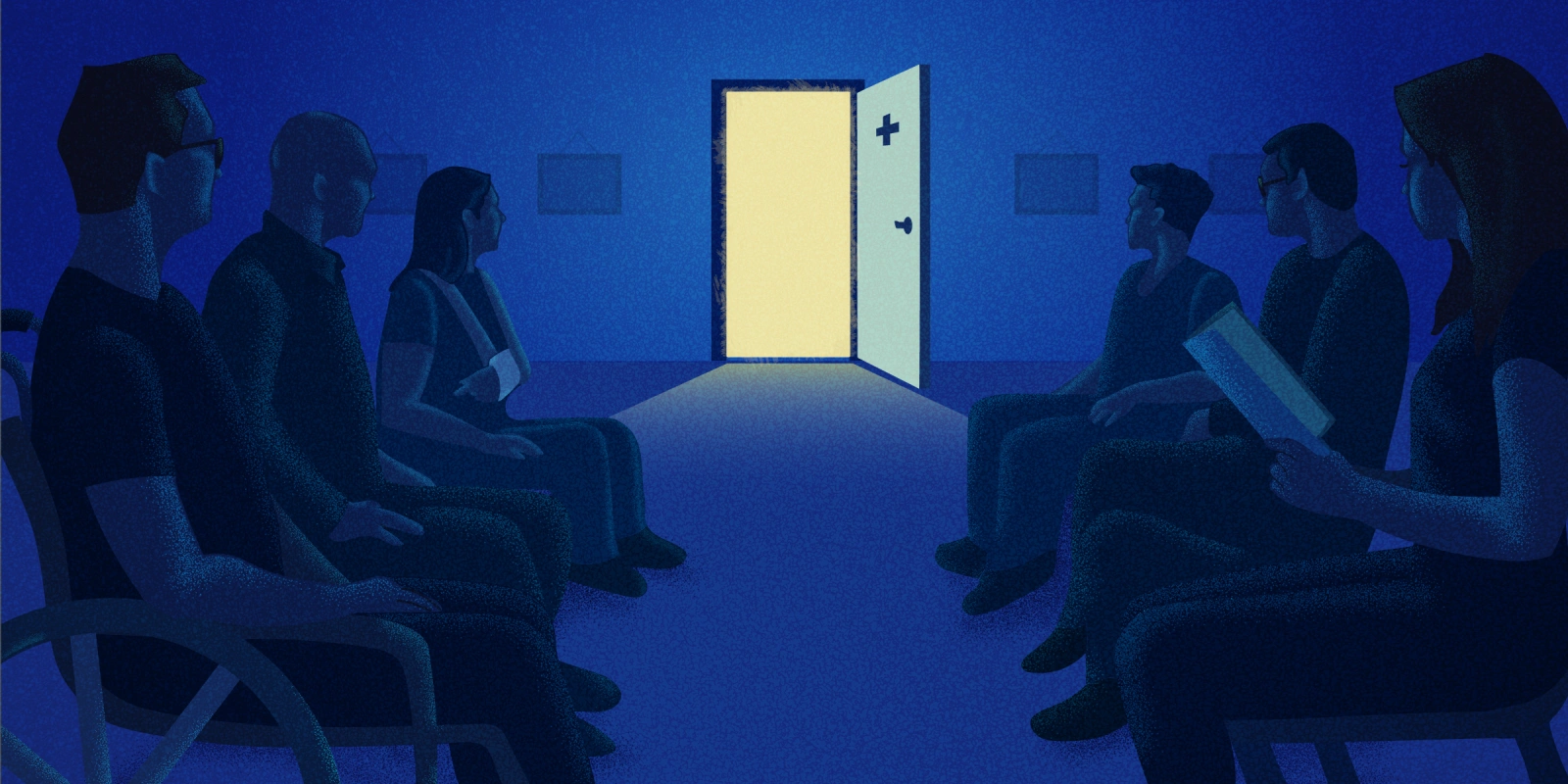

Illustration by Diana Connolly