I read an interesting article written by an internal medicine physician who did his residency at the same institution he attended as a medical student. In his final year of residency, he received negative feedback from an attending who had known him as a student. The attending criticized the resident for showing less enthusiasm about patient care as compared to when he was a medical student.

The resident is now an attending physician himself at an academic medical center. Upon reflection, he acknowledges that he was grateful for the criticism he received as a resident, because the gut punch ultimately made him a better physician. Indeed, this physician has virtually all five-star ratings.

I, too, chose to stay at my medical school to do my residency training (in psychiatry). I had done a senior-year elective at the main teaching hospital, essentially functioning as a first-year resident. So, I knew what to expect if I stayed there for my residency. Besides, I felt comfortable “at home,” and I had a positive experience that eliminated any concerns about choosing psychiatry as a specialty.

The faculty seemed genuinely interested in me. I had become acquainted with a few of them, beginning my freshman year and continuing into my senior year. One attending had actually interviewed me for admission to medical school years earlier. Naturally, I developed a close bond with him.

But what I hadn’t considered was the possibility that, since I was a “known quantity,” training where I went to medical school could impose some risks. Specifically, my “honors” performance as a medical student could have raised the faculty’s expectations of me, not unlike the aforementioned physician who was perceived to have been a failure for not becoming the doctor his attending thought he would become. Once people know your “baseline,” anything less might raise a red flag and invite unwelcome scrutiny of your performance.

After cruising through most of my first year of residency, I hit a brick wall – I was traumatized by a patient’s suicide attempt. I lost confidence in myself. I became depressed. I considered leaving the program. I confided in two attendings who knew me well from my third- and fourth-year clerkships. They persuaded me to stay. I did; however, I was put on probation. I entered psychotherapy with a psychiatrist I had known since my freshman year, and found that his therapy and droll wit were the perfect combination for my recovery. My probation was lifted in six months.

The faculty relationships I had cultivated as a medical student paid dividends in residency. The attendings appointed me chief resident in what was a déjà vu experience, because I had received an award for the best psychiatry student four years earlier. With the aid of the attendings, I was able to grow, thrive in my specialty, and contribute to the development and education of medical students and junior residents. I was humbled to be asked by the chairman of the department to join the faculty after my residency.

Had I not known at least some of the faculty as a medical student – and had they not known me – I doubt my training would have been so uniquely rewarding. Without the department’s support, I might not have finished training. It seemed harsh to have been put on probation, but I know it was not meant as a punishment. Overcoming my trauma through therapy allowed me to fulfill a promise to myself and my attendings to excel as a psychiatrist.

Whenever I counsel medical students about ranking residency programs, I always recommend they consider their own medical schools’ programs (assuming they exist). Hopefully, the students have made a few inroads with faculty who are approachable and enjoy helping medical students succeed. I urge students to seek out attendings whom they admire and can tap as mentors during residency training.

Medical students must entertain a host of variables when it comes to deciding where they want to train. Once they’ve decided on a specialty, they have to weigh a variety of factors, says the American Medical Association: geographic location, reputation of the program, work-life balance, the quality of the program director and other residents, and generally how good of a fit the program is.

Among U.S allopathic and osteopathic senior medical students, nearly half match to their first-choice residency programs. However, neither the National Resident Matching Program or the American Association of Medical Colleges routinely track the percentage of students who remain at their medical schools for training. The only information I found online was a forum addressing whether the residency selection process might favor “same place” medical students, and there was no consensus.

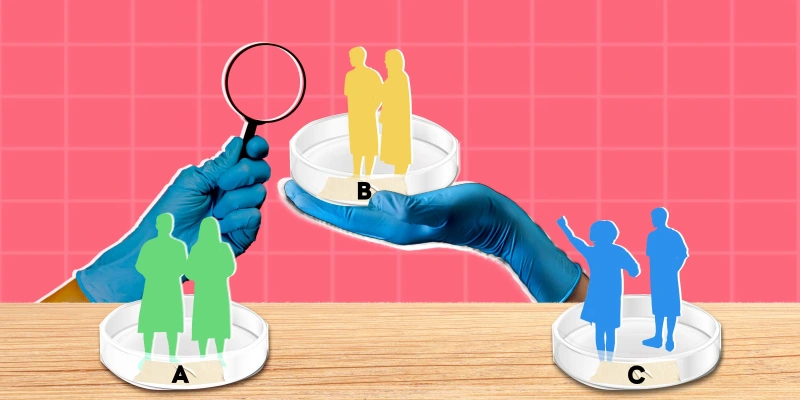

To gain further insight into the advantages and disadvantages of staying at the same medical school to undertake residency, I asked a few colleagues for their opinions. The advantages were perceived to be basic familiarity with the hospital layout and function, infrastructure (including EMR), and faculty, as well as nurses and essential support staff. Several physicians believed that preexisting knowledge of the surrounding area and city would quickly enable students to establish a work-life balance and good relationships with patients. The workload distribution between medical students, residents, and fellows would already be known, allowing residents to plan their time more usefully.

The major disadvantage was a perception that by not leaving their home institution, medical students would not broaden their clinical experience, and they would have less opportunity for growth and future practice opportunities. A gastroenterologist stated, “If you train at the same system for med school, residency, and fellowship, you only get to see one narrow approach to medical care.” An EM physician commented, “I've seen too many docs who went to residency and fellowship at the same program and they have no idea how the rest of the country practices.” However, the fact remains that regardless of where physicians train, more than half will practice in their state of residency training.

Transitioning from medical school to residency can be daunting because it means applying theory to practice. It means more responsibility. It means being under a microscope. Knowing what to expect can help ease the fear and allow students to better prepare for the next few years. This is as good a reason as any to consider one’s medical school as a place to train. In addition, if important groundwork has been laid in medical school, i.e., developing relationships with attending physicians, students are likely to succeed and even shine as residents at their alma maters.

Did you train at your medical school? What do you perceive to be the pros and cons? Share in the comments.

Arthur Lazarus, MD, MBA is a former Doximity Fellow, a member of the Physician Leadership Journal editorial board, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry in the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Image by Olga Strelnikova / GettyImages