I was approximately three months from our due date, January of this year. A baby was on the way. I was excited for so many things, and scared for so many things. My residency schedule had lined up perfectly: One of the senior residents was going to “bump” me out of the way so he could get some cases in before graduating. I was going to get our nursery ready and start on some things around the house that I had been “planning to do next weekend” for the last year.

Then the email came: So-and-so has to go get credentials for spinal oncology; it would be great if you could come back and cover the senior spinal resident position to see patients in clinic. While I was excited to get back to taking care of patients, something that I felt was somewhat taken away from me, I also felt a bit of remorse since I had lost all the dreams I had made for the months ahead. I started looking through all of my hospital’s policies, wondering how much leave I was “entitled” to as had been litigated by thousands of residents before me. The answer was unsatisfactory: two months paid, and a third available for extenuating circumstances.

My wife was navigating her own troubles in her job in education. She could get three months of unpaid leave if she applied through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act. It was great that she could get the time off, but patently unfair that her time serving the public school district would mean little when it came to leave.

This became increasingly difficult to stomach as we watched our friends and family working at big tech companies and unicorn startups taking up to a full year of paid leave. Not only that, the leave did not have to be taken continuously; it could be divided up and used over a whole year.

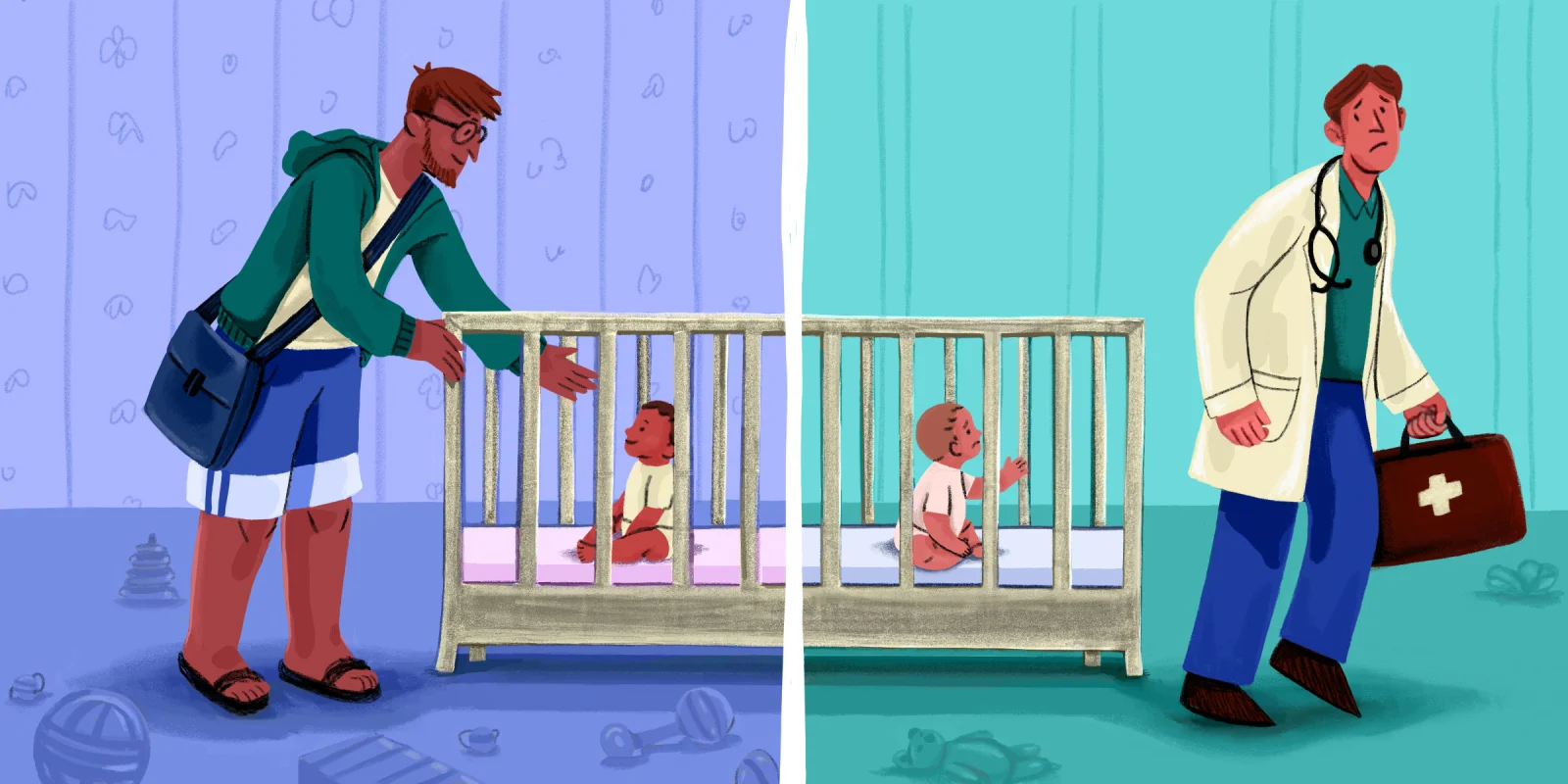

My wife and I have spent a major portion of our lives committed to service, myself through health care and her through education. Though it’s true that there are personal benefits to reap through the prestige associated with our professions in this country, it’s also true that we didn’t have the option to spend more than three months with our child. Our friends (whom a part of me felt like had “sold out”) were going to have the chance to see family and explore the world with their child. The developmental benefits for their children would be significant: a head start on social interactions, education, and physical skills.

When it came to comparisons with the tech industry, I was OK with not having a wellness room with a barista, ping pong tables, or cozy chairs to nap the afternoon away. I was OK sacrificing my potential earnings. I was OK with no stock options or ownership in the institutions I was supporting. I was immediately furious that my family was going to be taken from me.

There’s a joke in medicine, “Where do you hide a $100 bill from XYZ specialty?” Radiology on the patient, internal medicine under the bandage, EM in the chart. For neurosurgery, my specialty, the answer is "on their kid." I get the sentiment, but the system is set up so that that is the predetermined answer. It takes effort to see your kid, filling out forms, seeing doctors, validating your time away from caring for neurosurgical patients (still far too many to see with the current workforce). The baseline isn't, You’re going to take a year of time off over the next couple years to care for and develop your child, it's, Prove why your child needs you more than others.

This hurts, and I hope one day we live in a world where leave for childcare duties is a respected aspect of life. Perhaps it's selfish; however, I’d argue that prioritizing family affords a physician perspective to once again care unconditionally about life, and gives them the insight to translate this love to patient care. While the tech industry leverages this added perspective by prioritizing people, medical training demands that we run on empty as every ounce of productivity is used to treat an endless line of patients. What if this love for each other was pervasive among physicians — wouldn’t we all have a bit more empathy for everyone?

However, a rerouting of the system toward empathy and understanding will require breaking the current status quo of expecting physicians to pawn children off on others. The tech industry understands this and recruits on this benefit. In my pain as a physician parent, I have found a space doing that better and am humbled to learn from an industry which leverages supporting people into one of its greatest strengths. The cost is more expensive for everyone, but you never know who might really need it.

Are there aspects of the tech industry you wish health care would adopt? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Ryan Planchard, MD is a neurosurgery resident at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. He can be reached on Twitter @RPlanchardMD.

Illustration by Diana Connolly