Don’t cry over spilled milk was an idiom I’d hardly considered in my life before breastfeeding. After breastfeeding I did indeed cry over spilled milk — several times. Returning to work at six weeks postpartum, I had my younger sister “hook me up” to an apparatus that I had only seen from afar as a pediatrician and now: a breast milk pump. Between the microwavable bags, the buckets she had marked “clean” and “dirty,” the reusable labels we had purchased to date milk bottles, the flange sizes, and considerations about purchasing a deep freezer large enough to store an adult-sized human body, the preparation and ritual around what I’d witnessed other mammals do effortlessly was crushing. I remember thinking that I had not seen so much mysticism since my sixth grade dalliances with a Ouija board nor so many convoluted logistics since I had filed taxes for the first time.

Anesthesia medications, antibiotics, alcohol, antidepressants, marijuana, immunizations, and COVID-19 antivirals are just among some contentious items for breastfeeding people. But the bottom line is that for a healthy, term infant, the minimal expression of these substances within breast milk is often not a contraindication to breastfeeding. But that is not the bottom line breastfeeding people are receiving. Instead, they are met with ubiquitous and sometimes contradictory information that makes breastfeeding physically and emotionally more difficult.

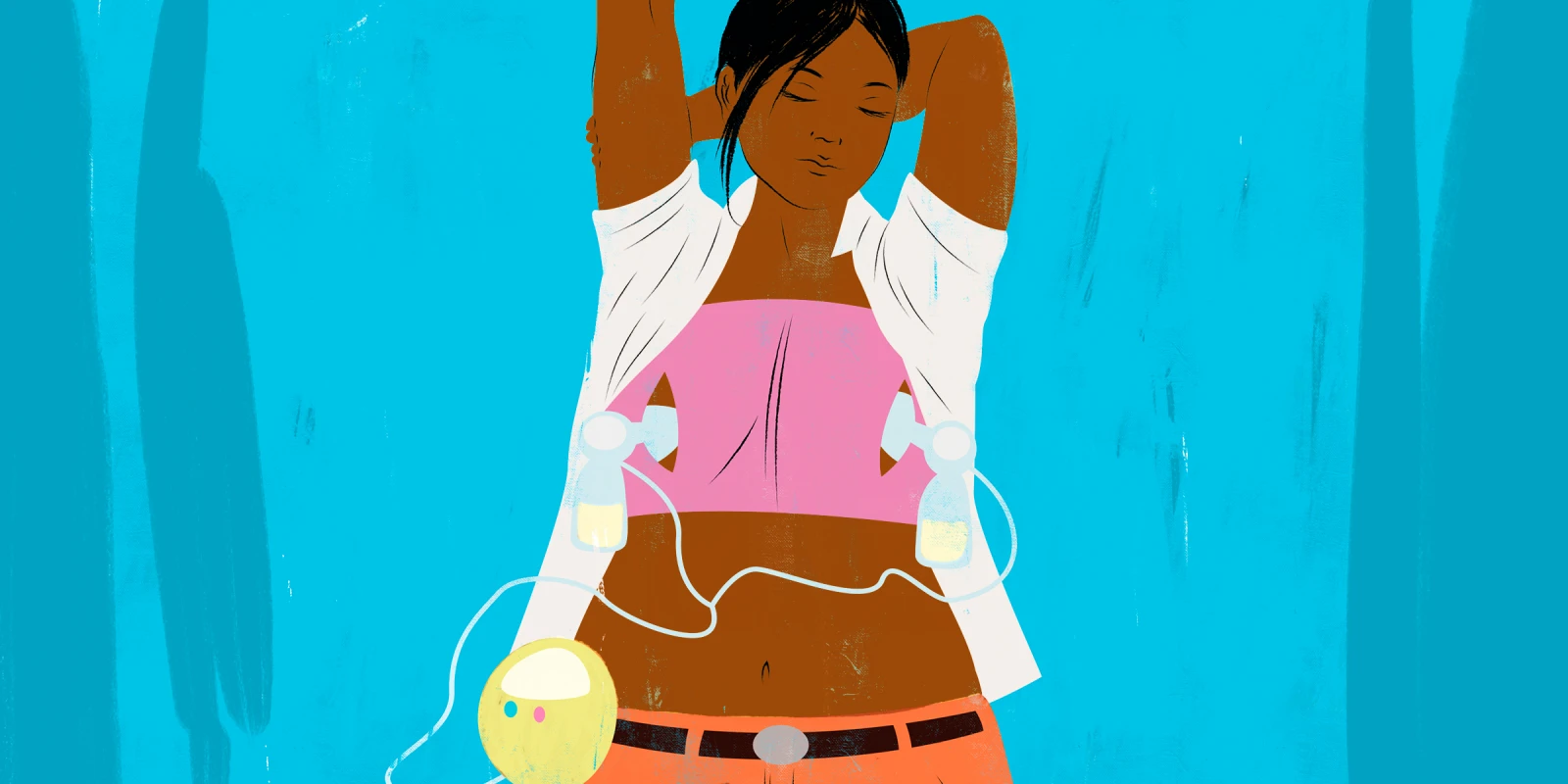

Residency had hardly prepared me for my own breastfeeding journey. While I had counseled many new parents with the confidence of someone who had never held anything in a football hold — including a football — the sheer terror of my daughter having anything less than an ideal latch was stultifying. Breast milk signified an almost theistic purity. With a perfect storm of postpartum anxiety, societal pressure, and maternal guilt, I decided I could not let anything impure touch her lips. In parking lots between patients or under the table during telehealth visits, breastfeeding demanded not only feeding my child, but constant sterilization of pump parts, freezing/thawing of milk, and changing of tubing. I was fully committed, though, no matter the toll on my time, sanity, or nipples.

When I needed my wisdom teeth extracted at three months postpartum, I nodded when the nurse asked if I was breastfeeding. “Well, maybe pump and dump for the next 24 hours.”

“Why?” I asked, immediately triggered by the notion of me pouring hours of work literally down the drain. As it turned out, the answer reflected the pervasive puritanical mythology of conception to birth which quite literally spills over into breastfeeding and controls not only women’s bodies, but everything those bodies produce.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) was compelled to release an addendum on its 2012 statement that “street drugs such as … cannabis can be detected in human milk, and their use by breastfeeding mothers is of concern, particularly regarding the infant’s long-term neurobehavioral development and thus are contraindicated” which was interpreted to mean THC use is a contraindication to breastfeeding. The statement was clarified to encourage breastfeeding even among those using marijuana, though it encouraged abstention.

A year later, the AAP released a broader statement that many lactating people are inappropriately advised to discontinue breastfeeding and/or discard breast milk despite the safety of most medications for infants. They now recommend referring to LactMed to confirm safety, but short of chemotherapy, the majority of medications, all immunizations, antidepressants, moderate alcohol, and even marijuana were not contraindications to breastfeeding.

The complete segregation of maternal health from infant health in the paranoia about breast milk is likely more damaging to both than trace amounts of medications.

Even when a person chooses to be a life-sustaining vending machine, they are smacked with a breastfeeding text that lends itself more to narrative history than literal truths. During the course of my own breastfeeding journey, I adhered to the mantra of “never pump warm milk into cold milk,” a dictate that effectively demanded sterilizing triple the number of bottles — only to have the recommendation quietly retracted by the AAP seven months later.

As it turns out, things can be simplified. Breastfeeding people are counseled to stop antidepressants, forgo a drink that represents some normalcy, and dump milk that takes hours to pump. In short, they are operating at the behest of advice that does not consider maternal well-being or even common sense — especially in the context of formula shortages which pressure people to breastfeed.

There are only two absolute contraindications to breastfeeding: an infant with classic galactosemia (an enzyme deficiency which prevents the processing of a milk-based sugar) or maternal infection with HIV. Unless you have a premature baby or one with an immunodeficiency, nipples and bottles only need to be sterilized once before first use and then hot, soapy water or the dishwasher is sufficient.

Emphasizing to breastfeeding people that they are more likely to do things correctly than not would be a huge boon to support both mothers and infants. The U.S. is one of the only countries in the world where paid maternity leave is absent. The Senate rejected the PUMP act to secure protections for breastfeeding mothers who were salaried (including teachers and nurses) during a formula shortage. We continue to perpetuate a culture where women are pressured to breastfeed despite logistical, political, emotional, and physical barriers. We need to at least move toward a culture in medicine which acknowledges how difficult breastfeeding is and at least simplify the evidence so that it seems attainable.

And for anyone who has made it through a full year of motherhood with themselves, their partner, and their baby intact, you’ve earned yourself a drink: no pumping and dumping required.

Megana Dwarakanath is a third year adolescent medicine fellow in Pittsburgh where she lives with her husband, Rahul, their young daughter, Meera, and their dog, Milo. When she is not spending time with friends and family, she likes to run, swim, and bike as well as read for as long as she can in one go. Dr. Dwarakanath is a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Image by Ken Tackett / Shutterstock