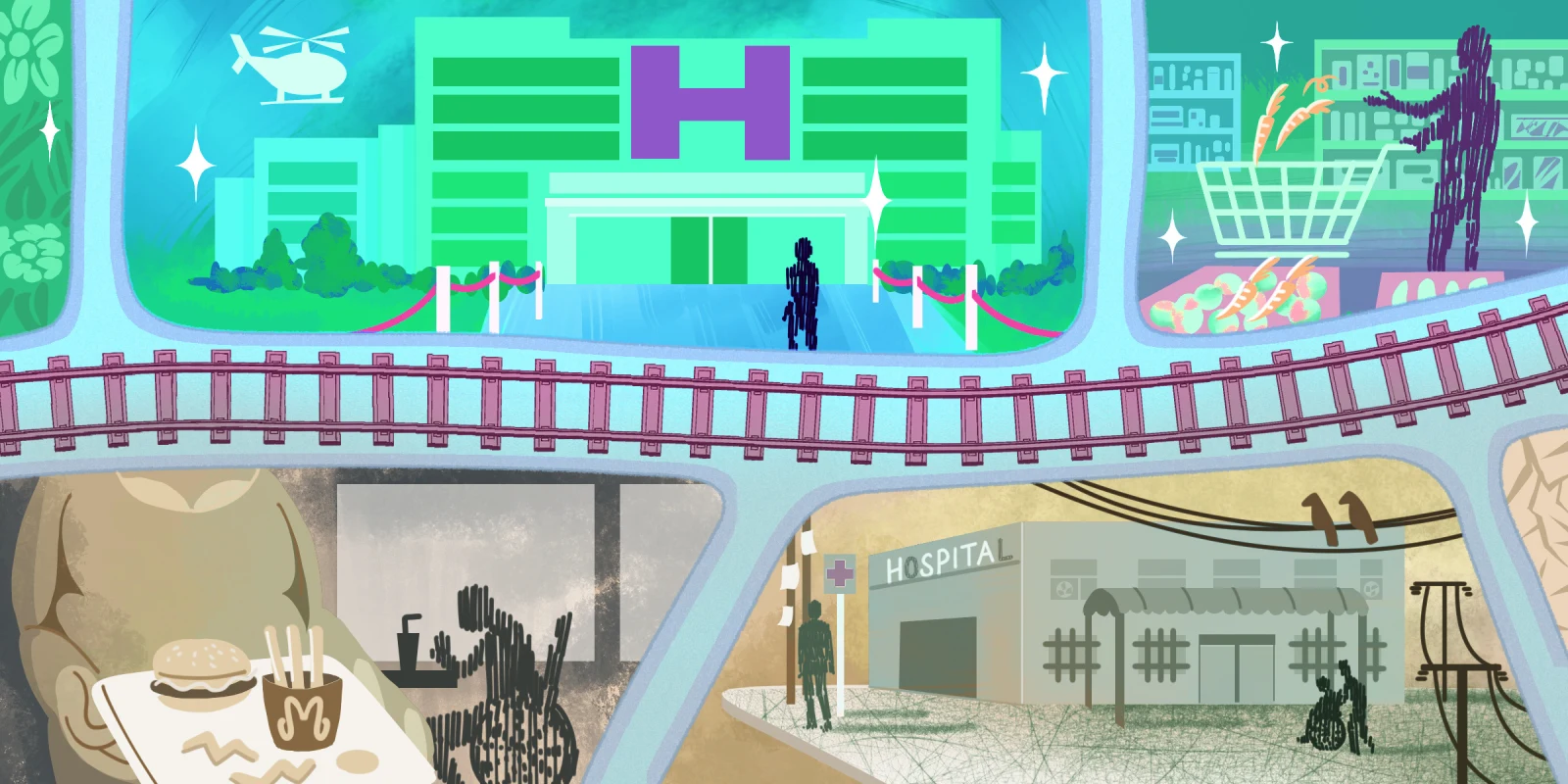

New York City is often hailed as one of the most diverse urban landscapes in the world. That diversity, while celebrated, comes with stark contrasts. As a medical student rotating through two major academic hospitals — one in Brooklyn and the other in Manhattan — I encountered firsthand the profound disparities between two patient populations that were geographically close but, in terms of their care experiences, worlds apart. Though separated by just a river, these hospitals educated me far beyond medical textbooks. They taught me that health care is not just about medicine; it is deeply intertwined with a patient's socioeconomic background, language proficiency, health literacy, and the resources and infrastructure of the hospital they access.

One rotation was at a hospital serving a largely immigrant population, many of whom spoke little to no English. The community was predominantly lower-income, with limited access to education and a high prevalence of patients without health insurance. For many of these patients, navigating the health care system was like entering a maze without a map. Their limited health literacy meant that they often had a poor understanding of their diagnoses, treatments, or the importance of follow-up care.

I recall an elderly man who spoke only Haitian Creole came to the hospital with poorly controlled diabetes and a severely ulcerating wound on his foot. The wound had not healed in months and was progressively getting worse. Despite the help of a translator, he struggled to understand the urgency of making lifestyle changes and managing his blood sugar. The language barrier slowed the encounter, doubling the time it took to explain to him the basics of his condition and the necessary treatments as I went back and forth with the translator repeating all my sentences. His situation was a troubling indication of a fractured care system.

This patient had tried to see his primary care doctor, but couldn’t get an appointment for four months. In the meantime, his foot wound worsened due to poor circulation and uncontrolled diabetes. His care was further complicated by an issue with his insurance at the pharmacy, which prevented him from accessing his prescribed medications. When he attempted to resolve the issue over the phone, the language barrier made it nearly impossible for him to communicate with his doctor and pharmacy team. As a result, from the time of his last hospitalization to his return to the ER weeks later, he had not taken any of his medications or received any wound care. Lost in the system, he returned repeatedly to the ER, using it as his default source of primary care — not by choice, but by necessity. This situation wasn't only about language barriers; it was a combination of education, access, and a health care system that lacked the infrastructure to support him adequately.

At this hospital, patients placed immense trust in us, their clinicians. However, this trust often stemmed from vulnerability and lack of an available alternative, rather than informed decision-making. These patients had little choice but to defer to us because of the vulnerable position the system forced them into. There was a heavy reliance on the health care team, and in many cases, the limited resources of both the patients and the hospital made it difficult to deliver the ideal standard of care. The hospital care team can only keep patients' heads above water. But when they have a lot of patients, little time, and when they're forced to also be primary care, people start to drown.

Across the river, in Manhattan, my rotation at an academic hospital presented an entirely different reality. The patients were mostly affluent, well-educated, and health-literate. Many came from diverse backgrounds, with private health insurance, access to specialists, and the financial means to pursue comprehensive care. Their engagement extended beyond receiving treatment — they were active participants in decision-making for their care.

I remember a businessman who came in with a pulmonary embolism. From the beginning, it was evident that he had an exceptional understanding of his condition and treatment options. He initiated a detailed conversation with the attending physician, weighing the risks and benefits of treatments like an inferior vena cava filter. He was highly engaged, asking questions about the imaging and scans he received and discussing his long-term care plan. Unlike the patients I had seen on my other rotations, this patient — and many like him — had the knowledge, resources, and agency to be fully involved in his health care decisions. There was no question of whether he would follow up with his primary care physician, pick up his medications, or adhere to his prescribed treatment plan.

What stood out most was the difference in the level of self-efficacy these patients had. Their access to resources enabled them to manage their care proactively, creating a dynamic of collaboration with the health care team. The difference wasn't just in financial resources or education but also in the hospital’s ability to coordinate care, provide seamless follow-up, and address potential complications before they escalated. The system worked for them, offering a level of support that allowed for meaningful engagement in their health.

These two rotations illuminated how a patient's socioeconomic status affects their ability to engage with their health care team and ultimately their health outcomes. The differences in resources at the hospital level — the ability to coordinate care, provide timely follow-up, and address patient needs — were equally critical. In Brooklyn, the lack of hospital resources coupled with low health literacy in their patient population created an environment where patients struggled to advocate for themselves. Conversely, in Manhattan, the hospital's infrastructure supported patients already equipped with the knowledge and resources to manage their care. This contrast taught me that health care equity is far more complex than simply addressing financial or access disparities. It's about ensuring patients have the resources, education, and system-level support to navigate their care.

As future clinicians, we must understand that addressing disparities in health care requires more than just improving access. It demands a nuanced approach that accounts for not only the socioeconomic status of patients but also the infrastructure and resources available at the hospitals where they seek care, a role that extends beyond the job of a physician. A one-size-fits-all approach to health care is insufficient, even within the same city. We need tailored policies, resources, and interventions that address each pocket of patients' unique needs per community. Hospital administrators must recognize that improving patient outcomes extends beyond patient-physician interactions. There needs to be an essential adaptation of health care delivery models to fit the specific needs of each site, meaning that certain patient populations require additional support that may look like multilingual communication options in all patient-facing departments, increased availability of late night and weekend appointments, and increased transportation and care coordination support.

True health care equity requires a deeper understanding of both patients and the systems that serve them. Only by addressing these disparities at both the patient and hospital level can we hope to provide the kind of care that everyone deserves, regardless of where they come from or which hospital they visit.

Have there been any eye-opening moments in patient care during your rotations? Share in the comments!

Shreya Jain is a medical student at SUNY Downstate College of Medicine in NYC and an associate at Quintuple Aim Solutions, a value-based care advisory firm. She's a native New Yorker, amateur skier, and eternal optimist. She writes about medicine, business, tech, and education on X at @ShreyaJainNYC. Shreya Jain is a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust