He was a 50-year-old man, developmentally disabled, who had spent most of his adult life in a group home. After suffering a series of falls, he arrived at the hospital with a bleed in his head that required a critical, lifesaving procedure. What happened next left me deeply unsettled — not because of the medical complexity, but because of what his case revealed about our system.

For two full days, this patient was in the hospital, receiving IVs, undergoing CT scans, and being treated with medications. Every step of his care required consent, yet no one had asked the most basic question: Who is legally authorized to make medical decisions for him?

It wasn’t until we needed formal consent for a procedure called a middle meningeal artery embolization that anyone realized the caregiver from his group home, the person who had been signing off on his care, had no legal authority to do so. In fact, there was no one formally assigned to make decisions on his behalf. No next of kin was on record, no medical power of attorney was in place, and no one had stepped in to fill this critical role.

What struck me even more was the realization that, had this patient been assigned to a different anesthesiologist, this issue might never have been discovered. It’s entirely possible the hospital would have continued on its course — conducting procedures, administering treatments, and obtaining consent from a caregiver who had no legal right to provide it.

But as chair of the medical ethics committee at my hospital, I have a particular focus, passion, and responsibility for these kinds of issues. My role has always driven me to ask questions others might not, to ensure that consent is being obtained from the proper person and that patients’ rights and needs are fully protected. This case caught my attention because of that passion — because I couldn’t look past the glaring gaps in advocacy and protocol. And that’s part of what’s so troubling. It shouldn’t take someone in my position, with my particular interest in these matters, to catch these oversights. The system itself should be designed to catch them.

What struck me most wasn’t just the gap in protocol. It was how easy it was for this to happen. This man had spent two days in the hospital, undergoing multiple procedures, without anyone verifying who was truly responsible for his care. It wasn’t malice or neglect; it was the sheer routine of assuming that someone else — anyone else — had already figured it out.

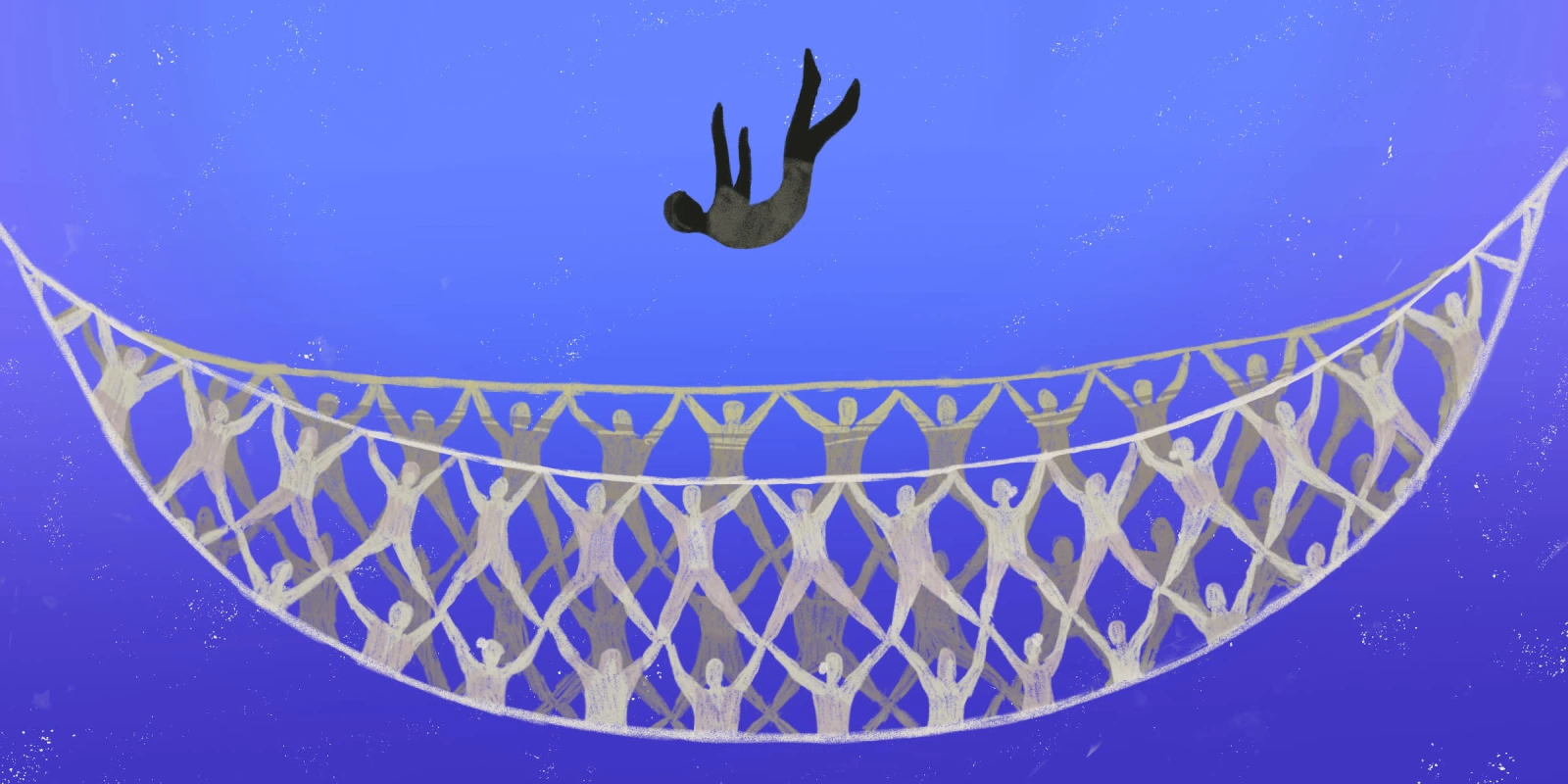

In a world where hospitals are equipped with cutting-edge technology, staffed by skilled professionals, and backed by countless resources, how is it possible that we still let people like this patient fall through the cracks? For individuals who are developmentally disabled, elderly, or otherwise vulnerable, these cracks aren’t small — they’re gaping voids. And when no one is there to advocate for them, it’s far too easy for their needs and rights to be overlooked.

What’s even harder to accept is that this failure doesn’t begin in the hospital. It begins long before. How is it that a 50-year-old man, with documented disabilities and a lifetime in the care of a group home, ended up with no one formally responsible for his medical decisions?

This isn’t just a health care issue — it’s a societal issue. It reflects how we, as a society, often fail to prioritize the most vulnerable among us. We place them in systems that are meant to provide care, but we don’t ensure they have the advocates they need when it matters most.

For this patient, we were able to track down an estranged brother to provide consent for his procedure. But what about the next patient? The one with no family, no one to call, and no system in place to protect them?

Why This Should Matter to All of Us

This experience left me with more questions than answers. Who speaks for those who cannot speak for themselves? Who ensures that their care is guided by someone who truly has their best interests at heart? And why are we, as a society, so quick to overlook their needs?

It’s easy to think that these are rare cases, exceptions to the rule. But they’re not. Vulnerable patients arrive at hospitals every day, often with no advocates, no plans, and no safety nets. And in the absence of clear protocols or systems to protect them, they rely on the assumption that someone — anyone — will do the right thing.

The truth is, we all have a stake in this. How we care for the most vulnerable among us reflects the values of our entire society. And right now, we’re failing them.

This experience taught me that we must do more to protect and advocate for vulnerable patients. Hospitals, in particular, are responsible for taking a more active role in ensuring that every patient has a clear, legal decision-maker from the moment they arrive. Here’s how we can start:

1) Early Identification and Verification: Intake protocols should include a mandatory step to verify the existence of a valid medical power of attorney, or MPOA. If none exists, a social worker or case manager should be immediately involved in identifying or appointing one.

2) Empowering Staff with Training: All health care staff must be trained to recognize red flags, such as when a caregiver or friend signs consent forms without legal authority. This training should emphasize escalating concerns and advocating for the patient’s rights.

3) Proactive Advocacy Teams: Hospitals should establish advocacy teams dedicated to supporting patients without clear representation. These teams can work in real-time to confirm decision-makers or initiate legal processes when necessary.

4) Policy and Accountability: Clear hospital policies should mandate thorough verification of all consent forms, ensuring proper documentation and accountability. Any gaps should automatically trigger internal reviews.

We can address the procedural gaps that allowed this situation to happen by implementing these steps. But more than that, we need a cultural shift — a commitment to truly seeing and advocating for every patient, no matter how complex their circumstances may be. Because, at its core, this isn’t about forms or policies. It’s about dignity. It’s about ensuring that every patient who walks through our doors is cared for — not just medically, but holistically, with their best interests at heart.

For me, this case was a stark reminder of the role we play in shaping a better health care system. It’s not just about treating symptoms or performing procedures — it’s about protecting the humanity of every person we encounter. And that starts with asking the right questions and refusing to let anyone slip through the cracks.

Dr. Ettinger is a board-certified anesthesiologist based in Dallas. He serves as the vice chief of anesthesia and the chair of the Medical Ethics Committee at a major Level 2 trauma hospital. Additionally, he is a commercial pilot and certified flight instructor, holding a degree in aerospace engineering. Dr. Ettinger founded Genmar Ventures, which owns and operates multiple Montessori schools in the DFW area. He has a keen interest in the intersection of technology and medical ethics, applying these concepts within the field of medicine. Currently, he is participating in the Entrepreneur Development Accelerator Program at MIT Sloan School of Management.

Illustration by Diana Connolly