In July 2021, we at Doximity asked our community members to tell us about a creative activity that helps them “blow off steam.” The winning submission came from Steven Immerman, MD, FACS, a general surgeon and kiln-formed glass artist.

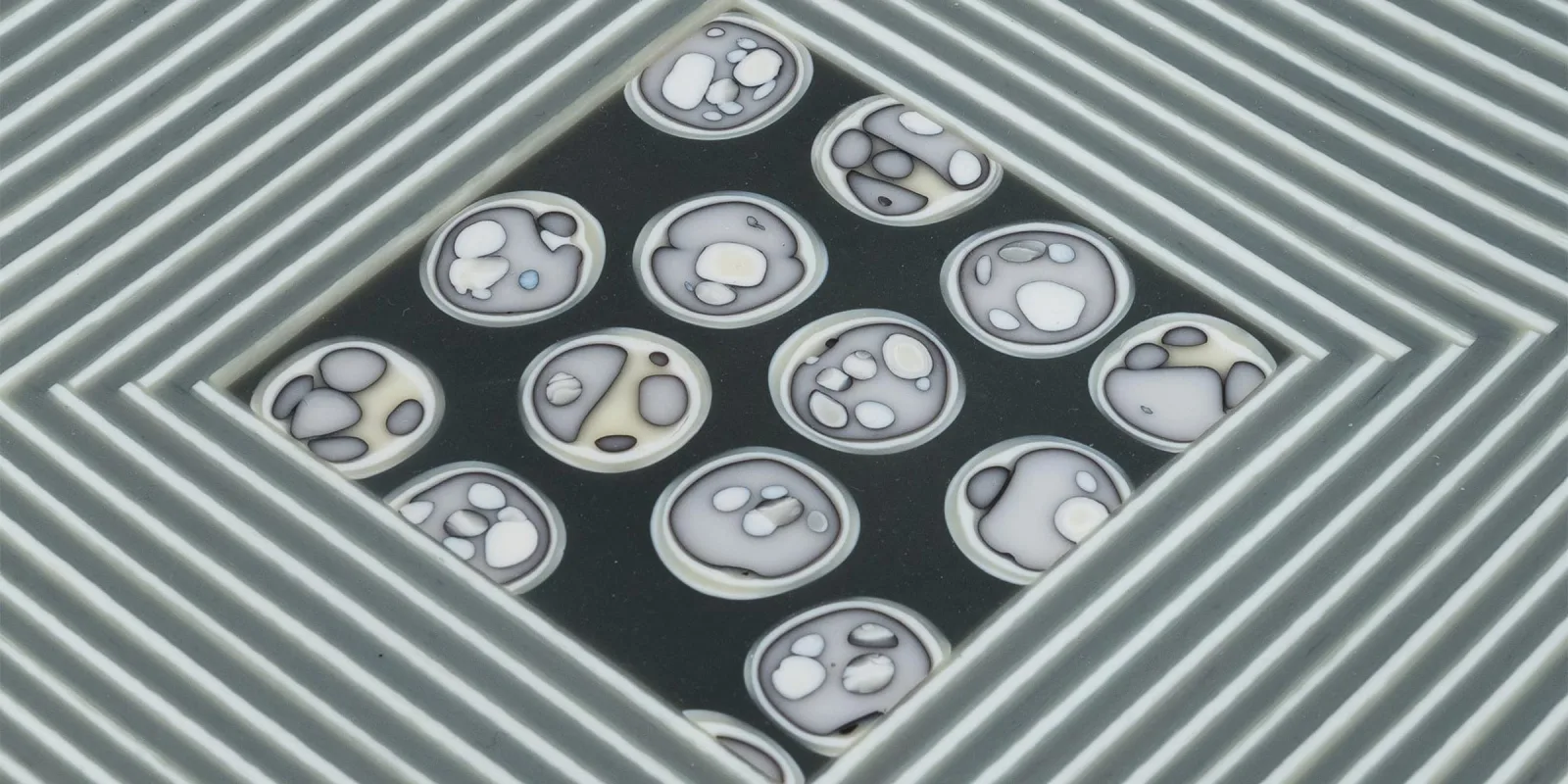

At an art and design workshop in Portland, Oregon, Dr. Steven Immerman eyed a pile of glass, contemplating his next project. He presented his plan to the teacher: a block of colored glass with a window through which viewers could observe the contents inside.

“The teacher comes over and tells me, ‘Well, of course. You're a surgeon. You make little openings in people and you look inside,’” Dr. Immerman told Doximity.

He then looked to his right at the design of his colleague, a retired architect, and saw a tiered structure that resembled a skyscraper. To his left, a retired engraver was grinding away at pieces of glass using a Dremel tool, much like his prior work as an engraver. Since that workshop long ago, Dr. Immerman has observed similar parallels between people’s choice of work and their extracurricular activities.

“You may not see it in yourself, but we all have certain patterns to the ways that we think. We do that in our work, but we also enjoy doing that in our free time, because that's who we are,” he said.

As far back as he can remember, Dr. Immerman has enjoyed creating and working with his hands. In that regard, his pursuit of surgery has been nothing short of ideal. He currently specializes in an advanced procedure for pilonidal disease, for which young people from all over the world travel to his Midwestern city of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, to receive treatment.

Kiln-formed glassmaking came to Dr. Immerman early on in his career, when he was jumpstarting a solo practice and had three children at home. “Though I was extremely busy, I knew I needed a creative outlet,” he said. “I found I really missed having a hobby in which I could use my hands. I was a surgeon at work, but even at play, I needed to work with my hands.”

He had previous experience with stained glass and was interested in glass blowing, but glass blowing demanded longer stretches of focused time than he could offer as the owner of a busy general surgical practice. While browsing an online forum on glasswork in the early ‘90s, however, he stumbled upon a relatively new style of art called kiln-formed glass. This new artform would allow him to work intermittently in a small home studio and, whenever his pager went off, step away from the art. The process relied on fusible glass from a Portland-based manufacturer that enabled glassmakers to fuse together sheets of varying sizes and colors.

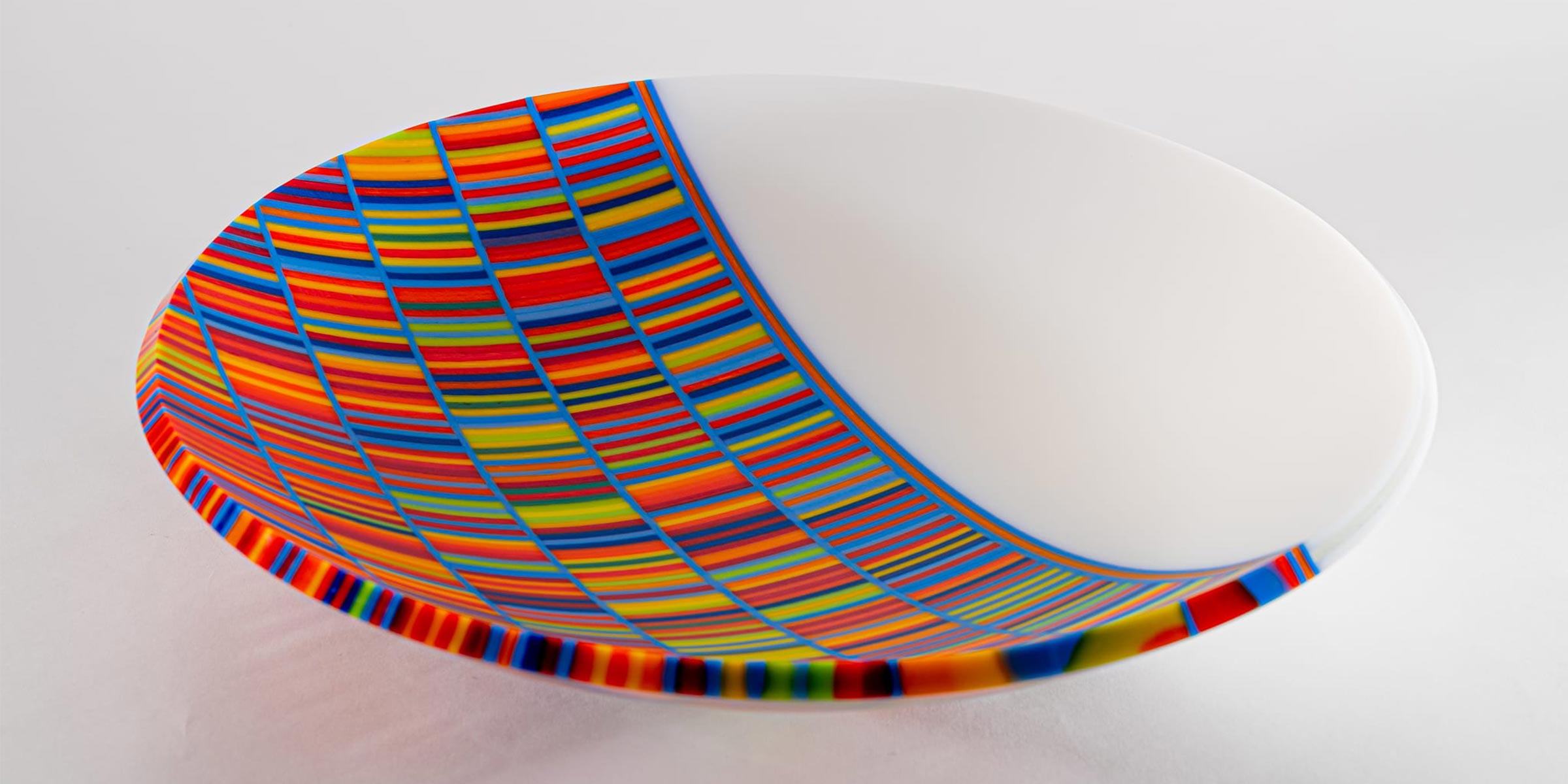

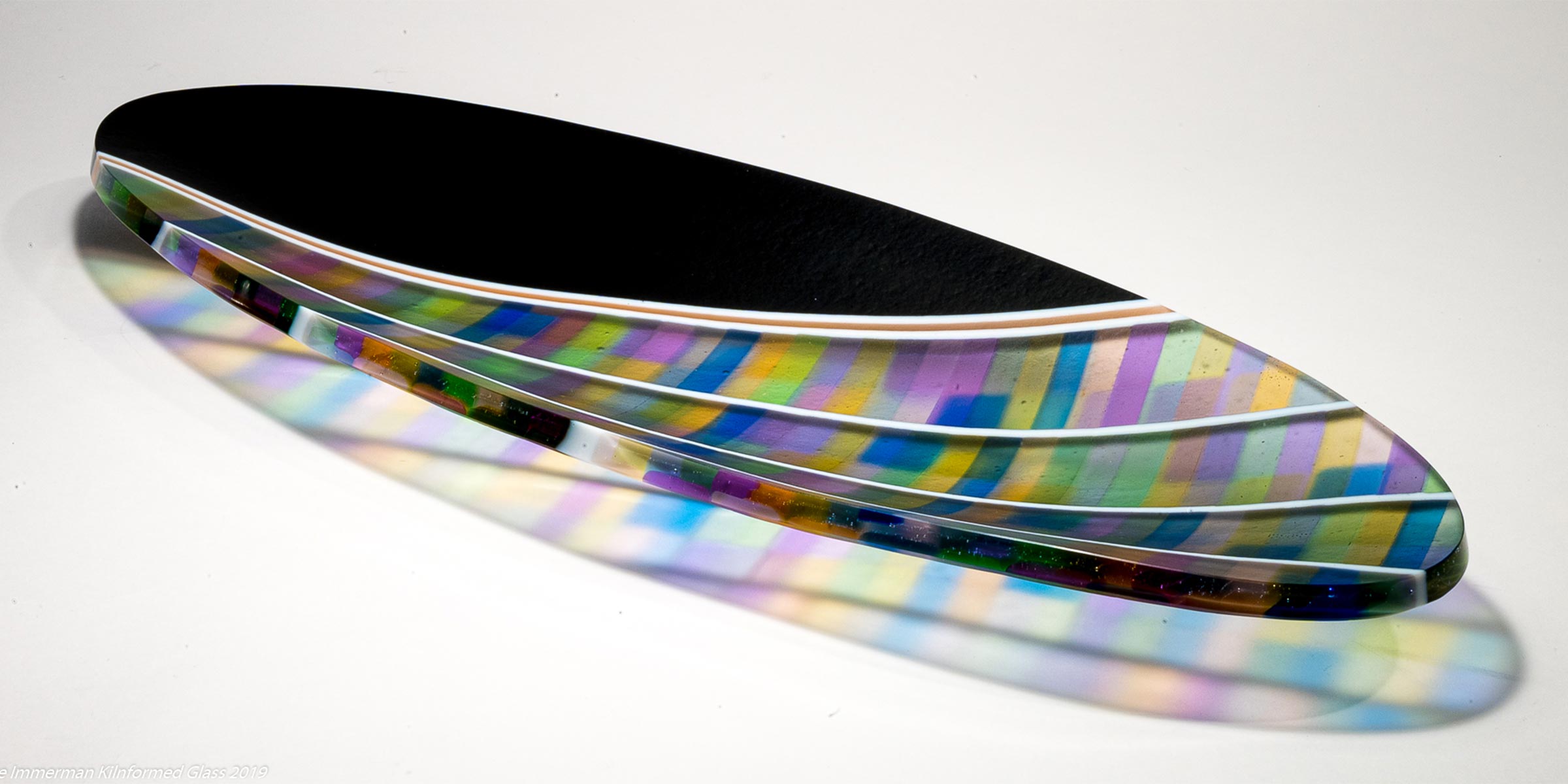

For Dr. Immerman, who most commonly works on small vessels and sculptures, the standard process entails cutting and assembling pieces of glass into a certain shape, setting them in a kiln, and then heating the glass at a fusion temperature of roughly 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit to fuse all the pieces together. Some projects require additional steps like polishing, grinding, or sandblasting for reshaping; and still others involve a process called “slumping,” or setting the glass in a mold before reheating it at a lower temperature. According to Dr. Immerman, the parallels to surgery abound: both require meticulous planning and preparation, both rely on an understanding of science and artistic ability, and both are fraught with high risk for failure.

The most profound parallel has been that the uncertainty that characterizes the waiting period after he performs an operation is also present after he sets glass in the kiln. “They both have a period of time when the process is seemingly out of my control,” he said. “For surgery, it is the patient's healing process; for kiln-formed glass, it is the time it is in the kiln. Then, hopefully, there is the joy of seeing the finished product in both endeavors.”

Beyond its similarity to surgery, kiln-formed glassmaking has given Dr. Immerman a creative outlet that quenches his thirst for artistic expression.

“I view the creation of my artwork and the enjoyment of the process to be the end in itself,” he said. “I’m not trying to make a message with my artwork. I’m just trying to create beauty.”

What’s more, he believes his passion for the art form brings him relief from the rigors of clinical work and makes him a better person. In conversation, he encouraged other clinicians to explore hobbies or activities to help reduce stress, be they restoring cars, collecting stamps, or writing a book. He further emphasized the value of trying something that is enjoyable and less stressful than work.

“Other physicians will say to me, ‘You’re so lucky you have this hobby,’” he said. “But there’s no reason they can’t have one also. You just don’t want to turn it into a second stressful career, because it's very easy to turn it into an additional stress, especially if you're type A and you're really good at something.”

Over the past few decades, Dr. Immerman’s artwork has been featured in galleries and auctions across the U.S., occasionally sitting alongside the works of world famous glass artists, including David Bennett and Dale Chihuly. Yet one of his most treasured experiences is an interaction he had with a client many years ago.

“There was a client who bought a piece from me, and she gave it to her daughter, who was a helicopter pilot in the Marines,” he said. “When she was away on active duty, it was stolen from her apartment. I took that as quite a compliment, and gladly made her another one.”

What would you like to read about? Share your suggestions on this form.

All photos courtesy of Dr. Steven Immerman. View his entire portfolio online.