“What’s the difference between the military and medicine? Only one has required yearly wellness checks to ensure they can do their job.” The correct answer may surprise you — it's not medicine. Retired Lieutenant General Mark Hertling said this during his breakout session at the annual Women in Medicine Summit in Chicago IL. In his session titled “My AAR: What I’ve Learned in My 2nd Profession”, Lt Gen. Hertling provided his outsider’s view of those in medicine. He spent 35-plus years as a military leader and became the senior vice president for an Orlando, FL based hospital organization after retiring. His insights were informed by spending the last decade training health care workers on how to be leaders. While much of the session walked through similarities between medicine and the military, one observation stood out to me.

Every year, all active-duty service members must complete an annual health assessment. This typically includes blood pressure and lipid screenings, but also dental exams, optometry and audiology checks, and colorectal/cervical screenings for cancer prevention. On the flip side, all practicing physicians must update their licensure every approximately 10 years to ensure they’re maintaining the clinical knowledge necessary to effectively treat patients. However, despite physicians being just as susceptible to cancer, vision problems, and cardiovascular disease as anyone else, there are no requirements for physicians to receive regular health screenings. Hertling revealed in fact that one of his physician colleagues had never undergone a colonoscopy.

Research studies also support this sentiment. Cancer was the leading cause of death in medical specialties (compared to heart disease being number one for the general population). The majority of physicians likely self-diagnose and self-medicate for both chronic and acute ailments, rather than schedule a health visit.

However, the belief that the military is better at taking care of its personnel is misguided; it’s focusing on the trees so much so that you miss the forest being on fire. While both professions differ in their approach to physical health, they share a similar deficiency when it comes to mental health and wellness.

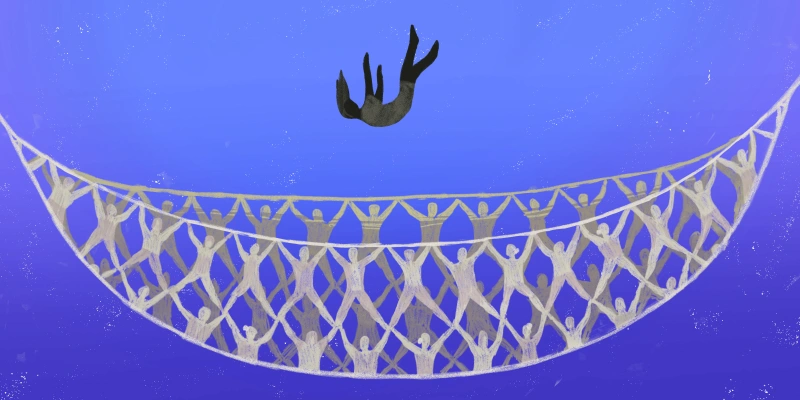

Nearly 16 veterans die by suicide every day. One in 10 physicians considered or attempted suicide in 2021; these suicide rates are more than double the rate found in the general population. Both professions are physically demanding – personnel are required to be on call for long hours, are deployed at a minute’s notice, make personal sacrifices, and withstand society's unwavering expectation of expertise and infallibility. However, beneath these professional requirements lies an underlying issue that contributes to their poor mental health: the reluctance to acknowledge when they are struggling. Active-duty members and physicians alike admit that fear of embarrassment or professional repercussions often prevents them from seeking psychological help.

How do we encourage those trained to "protect the United States" and those trained to "treat the people in the United States" to take care of themselves? Discussions about self-care and burnout have gained momentum in recent years. As a medical student, I am often told by my advisors and mentors to treat medicine "like a job," "make sure you have hobbies," and "prioritize work-life balance" While these recommendations hold true, they are a Band-aid fix. It’s appreciated to receive complimentary cookies for wellness, but that gets overshadowed by the fact that it was the only thing I’d eaten beyond mini pretzels that day. They overlook the institutional barriers that hinder genuine well-being.

For example, we attend mandatory wellness seminars and after-hours lectures, allowing organizations to check off a box, while simultaneously penalizing us for taking time off for mental health, disabilities, and chronic illnesses. At a senior level, employers claim to prioritize physicians' well-being, yet they shorten appointments to increase patient volume, heighten the burden of technological documentation, and rely on a revolving door of travel nurses and visiting doctors due to their inability to retain a stable staff.

The same holds true for those of us still in training. The ACGME mandated we may only work an average of 80 hours per week, but this has only increased the intensity of work that needs to be done in fewer hours.

“You feel like you do EVERYTHING for every single patient,” a pediatric first-year resident said, summarizing the sentiment well. “It’s like carrying the entire patient load the entire day (like a typical call night – but for the daytime calls too!), and you never sat down. Never.” Some studies have even found residents violate their duty hours to properly treat patients.

Our current efforts to create safe and healthy working environments look like leaps on paper; but in reality, they are miles away from ensuring physicians are not burnt out, and are instead mentally healthy and satisfied.

Wellness can take on many forms. I have been fortunate to see some of these initiatives through personal experience and anecdotes from other institutions. Some residency programs give residents periodic wellness afternoons during which they have a built-in half-day to attend doctor’s appointments, spend time with their family, or merely relax. I spent time during my first year of medical school learning about the mistakes and setbacks my faculty had experienced; they made it more acceptable to speak about our mental health without judgment. It requires a culture shift in tandem with structural changes if we want to see real improvement.

I’d like to offer a revision to Hertling’s initial statement. What’s the difference between the military and medicine? Both have discovered unique ways to shift the responsibility of wellness onto those affected, rather than holding institutions accountable for the systems they have created. And to that I say, advocate for institutional change and fill those executive positions so we can build medicine into the environment we deserve to work in.

Ifeoma Ikedionwu is a third-year medical school student at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. She has interests in mental, reproductive, and disability health, especially for minority groups.

Collage by Jennifer Bogartz / Shutterstock