"I really want to come see you – but I just can't take the time off work." This is the typical refrain I hear from patients. I'm a Psychiatrist specializing in Women's Mental Health in Washington, DC. My patients are well-educated, well-resourced, and VERY busy. When depression and anxiety hit, it's not so convenient to stop by your local psychiatrist's office every week. I get it. But, what usually brings women back to my office is when their suffering starts to affect those around them – their children, their partner, their co-workers.

I recently returned from a trip to India where I presented my research studying women with depression at the Marcé International Perinatal Mental Health Conference. As some of you may know, I am a 1st generation South Asian American and spent a good part of my childhood in India. South Asian Hindu culture is largely based on traditional gender roles and these dynamics loomed large in my upbringing. My undergraduate and graduate education were done in urban research institutions where I was exposed to views questioning traditional gender roles. I chose to formally study gender as a Women's Studies Major and dual majored in the Biological Basis of Behavior at the University of Pennsylvania, before going on to obtain my medical degree from Jefferson Medical College. My desire to integrate my South Asian heritage and to resolve the dichotomy between traditional gender roles is the lens through which I approach both my professional and personal lives. Back in Washington, as I reflect on this particular trip to India, I've noticed patterns between these two worlds.

A few years ago I conducted a small ethnographic research study working with rural Indian woman who lived on the outskirts of Bengaluru. I completed the field-work for this project when I was a psychiatry resident at the George Washington University, through their Global Mental Health Program. These women were all mothers seeking treatment for depression or anxiety at a community clinic through the National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences in Bengaluru. Interestingly, the majority of women had daughters, and their average level of education was 4th grade. Our project was qualitative, meaning that we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews and a focus group with the women. We were not so interested in their diagnosis, symptoms or medications. Instead, my attention was on uncovering a nuanced understanding of the experiences of women living with depression and anxiety in a country where there is tremendous discrimination against mental health and against women. We wanted to understand how they made sense of their depression: what was the problem and what did they believe caused it? What had them finally decide to get help?

The women spoke almost exclusively about their interpersonal lives. They attributed their illnesses to problems with their husbands (philandering and drinking away household income) or their mothers-in-law (overworking and belittling them). And, lest you jump to the conclusion that this was all in their heads – the evidence backs it up: Gender disadvantage factors like sexual violence, low autonomy in decision making, and decreased family support are independently associated with an increased risk for developing depression and anxiety in South Asian women. We know that depression lives and breathes within the walls of family life for South Asian women.

What surprised me was these women from rural Indian villages had similar motivating factors for getting help as my patients back in Washington. They conceptualized their illness within the structure of motherhood, and their treatment seeking within the framework of being a good mother. Children, and taking good care of them, appeared to be a socially sanctioned means for women to assert agency in the face of a patriarchal family structure. In other words, it was difficult for women to be open about getting help. It could be dangerous and bring shame onto the family. But if they made the choice for the sake of their kids, then treatment for mental illness became valuable, even a priority. One interpretation of this phenomenon is that it is a protective defense mechanism. These were the resilient women – the courageous few who traveled hours, sometimes secretly, to get treatment.

You see, I hear this type of thinking over and over again from my patients. It's hard to ask for help and speak up unless you feel you're doing it on behalf of someone else. It seems impossible to justify spending time and money on your own mental health. It might even be self-indulgent! What is it about being a woman that makes it hard to admit to yourself and to others that you are suffering? Why is making that admission easier when it also unburdens someone else? I'm not a mother, but through my own work in therapy, I've come to understand that it's no coincidence I landed in a career which has me healing the emotional wounds of others. Most days, it is a joy and a privilege to bear witness to my patients' internal worlds. But to keep it that way, to keep myself feeling generous, it requires a great deal of work on my part. As women in medicine, I think we bear an even heavier load of this compulsion to self-sacrifice.

I should be clear and state that I'm not equating the suffering of rural women in low and middle-income countries with that of upper-middle-class women in the West. What I am pointing to is when I look underneath, I find a kernel of truth that exists in both worlds. It might be radical to draw a clinical comparison between women's' seemingly endless ability to self-sacrifice and the patriarchy. Yet, we know that across the board, women are penalized for showing too many feelings, for being too assertive, for asking for too much.

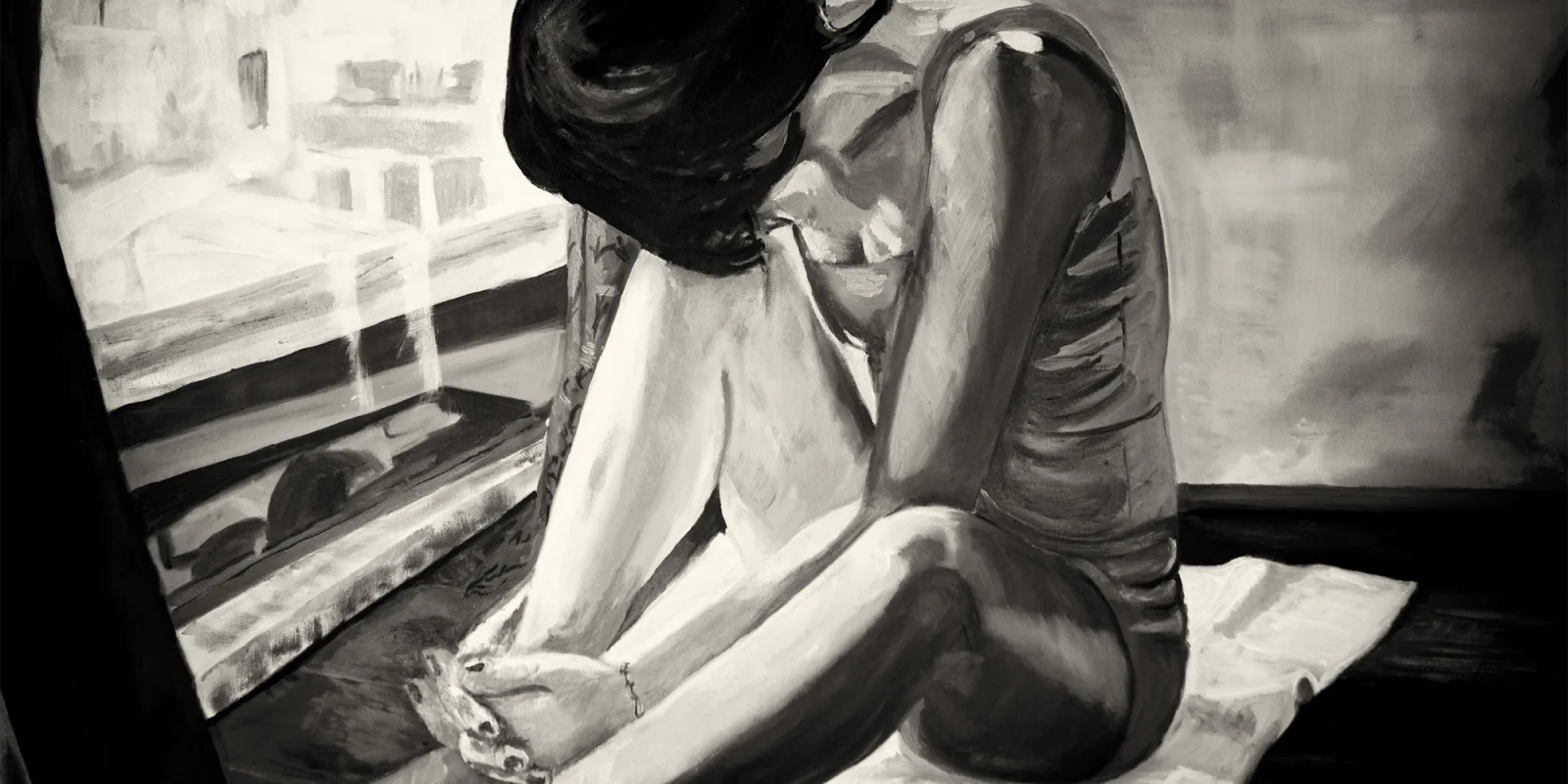

Oppression and misogyny make you feel small on the inside – no matter what continent you live on. It feels like you don't matter. Like there is no space for you. Like being you is a burden to others. That it would be easier if you did not exist. Certainly, many of these feelings could be symptoms of clinical depression. But, they also describe what it's like to be a stigmatized group who has learned to survive by catering to the powers that uphold the system.

Pooja Lakshmin MD is a board-certified psychiatrist and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at the George Washington University School of Medicine. She is passionate about women's mental health. You can find her on twitter @PoojaLakshmin. She is a 2018-2019 Doximity Author.