Article last updated August 15, 2022

Since the first monkeypox case was reported to the WHO on May 13, the virus has spread rapidly in the U.S. As of August 10, there are 9,492 cases in this country, more so than in any other.

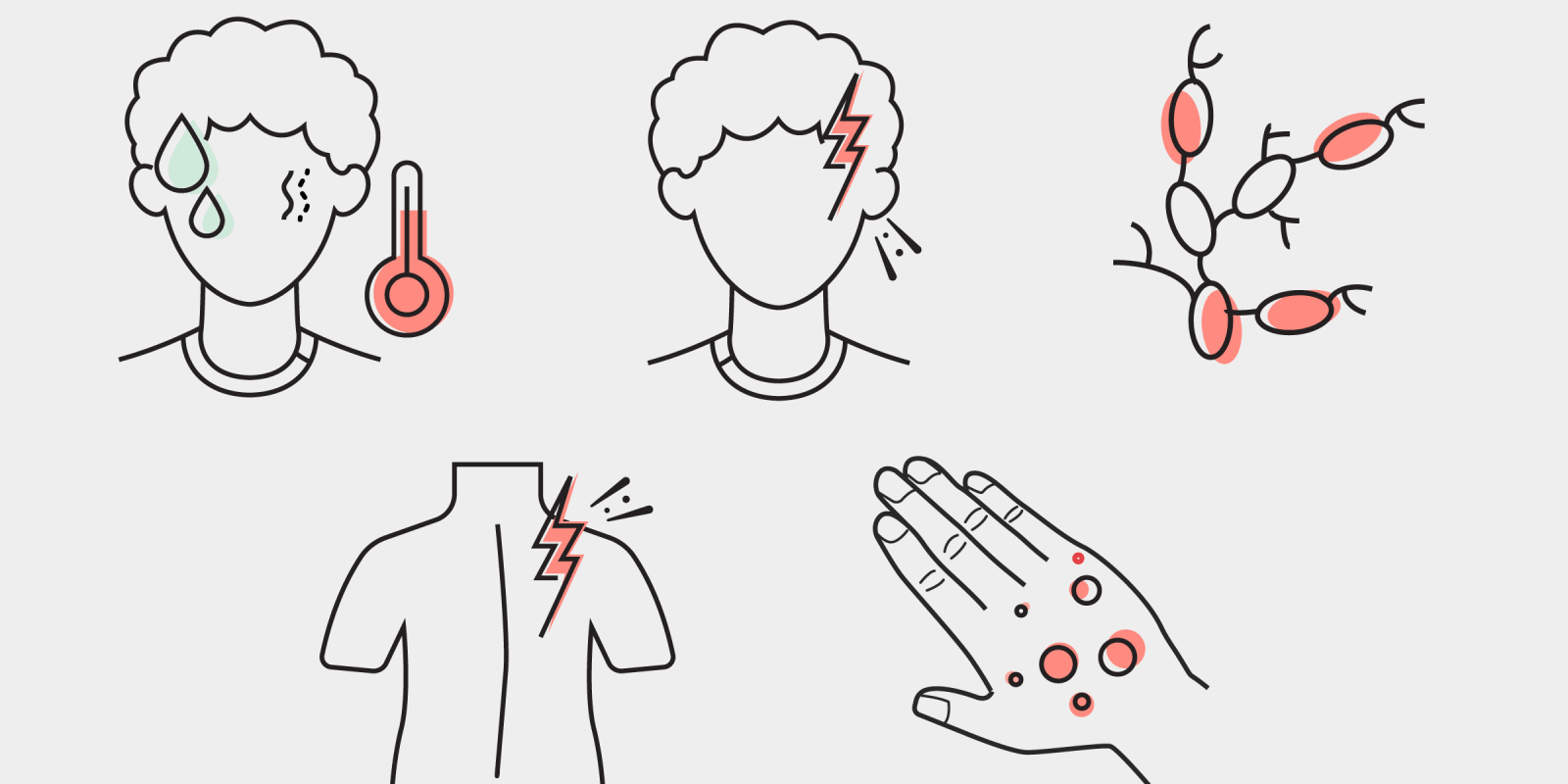

Monkeypox is transmitted through close skin-to-skin contact, respiratory secretions, fomites and possibly other bodily fluids (e.g., semen, saliva). Other symptoms in addition to the characteristic monkeypox lesions include fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, exhaustion, muscle aches, headache, and respiratory issues. Anyone can get monkeypox if exposed. At this time, the virus is primarily spreading in men who have sex with men (MSM). Men comprise 98% of cases and 38% of total cases are in HIV-positive individuals (as of July 22).

Vaccines

The CDC has authorized access to two orthopoxvirus vaccines, JYNNEOS and ACAM2000. The JYNNEOS vaccine has been allocated to known contacts of monkeypox cases as well as high risk individuals such as men who have multiple male sex partners (guidelines will likely change over time as more vaccine is available). On August 9, the CDC authorized the distribution of smaller doses (one-fifth of the regular dose) of the JYNNEOS vaccine in order to stretch the amount of doses available. The smaller dose of vaccine would be administered intradermally, as opposed to subcutaneously. This is a known principle in vaccinology, to try to spare doses by administering them intradermally.

Testing

HHS has expanded testing capabilities for monkeypox to include both the U.S. Laboratory Response Network as well as commercial laboratory testing. Testing requires a visible lesion to be swabbed, and it is recommended that testers collect two to three lesion specimens.

Medication

Tecovirimat (TPOXX) is an antiviral medication developed for smallpox from the Strategic National Stockpile and has been proven effective in studies of non-human primates infected with monkeypox. The CDC holds an EA-IND to use TPOXX for emergency use in humans with monkeypox. Patient visits for TPOXX can be done in person or via telemedicine, and forms for the EA-IND must be returned to the CDC after treatment begins.

Commentary

In an interview with Doximity, two UCSF infectious disease experts, Dr. Monica Gandhi and Dr. Seth Blumberg, commented on the current status of the monkeypox outbreak in the U.S. and treatment guidelines for clinicians.

Doximity: Many cities have run out of monkeypox vaccines. What is the plan for a roll out of more vaccines in the U.S.?

Blumberg: In July, HHS announced it has purchased enough of the JYNNEOS vaccine for two million people. It will take the manufacturer some time to deliver the vaccines. Thus, key components of vaccine distribution include 1) identifying the highest-risk individuals; 2) distributing available vaccines to the highest-risk individuals in an equitable manner; 3) making treatment available to those who contract monkeypox before getting vaccinated; 4) deciding if it would ever make sense to distribute the less-safe, but more available ACAM2000 vaccine.

Dox: Do you think there are people who have monkeypox that aren’t being tested?

Gandhi: Yes, there likely are more cases than those which have been tested, although I suspect a lot of the cases are actually getting diagnosed because the infection 1) presents with lesions that can be painful so seeking care for symptom relief may be more common; 2) the media coverage on monkeypox has raised awareness among MSM, the population most at risk who has been alerted to get testing; 3) testing capacity has increased.

Dox: Do you think there’s misinformation spreading about this virus?

Gandhi: Yes, I think the misinformation on monkeypox seems to be generating more fear, but this misinformation is around denial that the virus is being spread by close skin-to-skin or respiratory contact, but is being spread by casual respiratory contact. There is no evidence of this and the cases would be much much higher by now if monkeypox spread in the same manner as COVID-19. The other piece of misinformation is denial that the group most affected is MSM, but it is important to acknowledge this reality to get more resources (vaccines and treatment) to this population.

Dox: What can clinicians do to prevent the spread of monkeypox in the health care setting?

Blumberg: As with any infectious disease, there can be a small risk of health care providers acquiring a disease during an inadvertent exposure with an infected patient when no precautions are taken. However, by maintaining diligent adherence to infection prevention guidelines, this risk of interacting with monkeypox patients is minimal.

Dox: What can clinicians do to help prevent the spread of monkeypox in their communities and among their patient populations?

Gandhi: Advise patients to not have sex if they have active lesions or were exposed to someone with monkeypox for a few days to ensure they didn’t get infected. Advise on condom use since the virus is found in semen so may be passed partially via this route. Getting vaccines when available will help prevent spread.

Dox: What communities are considered high risk for monkeypox?

Gandhi: MSM with multiple sexual partners are the highest risk followed by all MSM with a lower number of partners.

Dox: How can physicians identify high-risk patients?

Blumberg: The highest-risk patients are those that have a risky exposure and classic symptoms. Risky exposures include intimate contact with someone known to have monkeypox, or attendance at an event involving a lot of physical contact where there are known to have been many monkeypox cases.

Dox: How can clinicians reduce stigma around monkeypox?

Gandhi: Just be calm in your delivery of care. I do not think it is stigmatizing to point out a certain population is most at risk of an infection. In fact, identifying the population most at risk of a disease is empowering so that resources can be directed toward that population.

Blumberg: I think clinicians need to be transparent about what we know, while also advocating for the sub-populations that are at highest risk. In addition, no one should be blamed for getting monkeypox — just like a hiker in the northeast should not be blamed if they happen to acquire Lyme disease.

Dox: Are there any new treatments being developed or innovative treatment methods that clinicians are using?

Gandhi: The evidence is still being gathered on tecovirimat or TPOXX in terms of effectiveness. In terms of what we know so far, there have only been non-randomized, unblinded investigations of the efficacy of tecovirimat against monkeypox infections in humans and that data is encouraging. The U.S. CDC currently recommends tecovirimat be used under an EA-IND for 14 days for patients with severe monkeypox infection or those who are at risk for severe monkeypox infection and there is an IV formulation available for inpatient use.

Dox: What can high-risk patients do as post-exposure prophylaxis if they are unable to receive the vaccine in their area?

Blumberg: Currently vaccination is the best post-exposure prophylaxis that is available. If a high-risk patient cannot get a vaccination, I would encourage them to be aware of clinics that can provide rapid diagnosis and treatment if they happen to develop signs and symptoms of monkeypox.

Dox: Should patients ever go to the ER for monkeypox?

Blumberg: There are several indications for when patients with known or suspected monkeypox should go to the emergency room. These include inability to swallow, shortness of breath, chest pain, and worsening vision. These all suggest that monkeypox may be affecting an important organ. Another reason to go to an urgent care or emergency room is if a monkeypox blister suddenly becomes much more swollen or starts draining pus, as this may be indicative of a secondary infection.

Dox: Do you think confirming monkeypox as an STD would help or hinder efforts to limit spread of the virus?

Blumberg: If monkeypox is confirmed to be an STD (meaning that it can transmit via semen or vaginal fluids) this could both both help and hinder efforts to limit the spread of the virus. On the positive side, this might mean other routes of transmission (e.g., droplet or fomite spread) are less consequential. On the negative side, it would imply that sexual partners could transmit disease via barrier-free insertive sex even when there are no skin lesions.

Resources

Additional Resources for Clinicians:

- CDC COCA Webinar from July 26, 2022 focusing on the monkeypox outbreak

- CDC Information for Healthcare Providers on Obtaining and Using TPOXX (Tecovirimat) for Treatment of Monkeypox

- CDC: Monitoring People Who Have Been Exposed

- CDC: Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines during the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak

- CDC: Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for Preexposure Vaccination of Persons at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses

Interview conducted by Melina Tessier

Image by DesignPrax / shutterstock