There has been a recent push toward institutionalizing protections for breastfeeding in the workplace, in part due to strong support for such policies from major national and international health organizations, including the AAP, ACOG, the CDC, and the WHO. While the environment is more conducive to breastfeeding than previously, it is still by no means a permissive one; this includes corporate America as well as the healthcare workplace. No standard agreement exists on what constitutes "appropriate" accommodations for breastfeeding needs, and there are potential career ramifications across the board for moms who choose to work while breastfeeding.

Physicians in particular face a unique set of challenges to breastfeeding, especially with the relative inflexibility of clinical medicine. In a JAMA Internal Medicine study this year, less than one third of physicians surveyed met their goals for duration of breastfeeding, with barriers including inadequate time, insufficient space, and a lack of adequate maternity leave. Of course, some of these barriers are more conducive to change than others, but a little bit of creativity can go a long way. For example, more than half of those surveyed said they would have breastfed longer if they had a private space to pump.

When I was a medical student, my institution had a policy that protected breastfeeding employees, in addition to dedicated pumping rooms with locked doors, hospital-grade breast pumps, sinks, and refrigerators. This is a progressive setup, and it is important that we are starting to identify and address the barriers to breastfeeding in our workplace. It is equally important, however, that we consciously work to extend this culture change to all levels of the profession, including medical students, if we want to institutionalize it.

I successfully breastfed my first child through my first year of medical school with relatively few roadblocks; my lecture schedule was relatively flexible and my professors were accommodating. There were a few more challenges when I was breastfeeding my second child during my clinical years. I still worked out schedule accommodations with my attendings and supervising residents, but there was less flexibility to do so. I lugged my pump with me to rotations at outside sites, where I often found myself pumping in a storage room or closet, sometimes without a lock on the door. I got comfortable pumping in a variety of environments, including in public places with my equipment hidden under my shirt or beneath my coat if necessary.

On one of my rotations, I was not permitted to miss morning lecture, and it was right during the time I needed to pump. There were required meetings before and after this lecture, so despite trying to find a good time in my schedule, there just wasn't one. I settled on sitting in the back corner of the lecture hall with my pump under my shirt for the first 15 minutes of lecture so that I could fulfill my responsibilities and then go on with the rest of my day. After about two weeks, I was called into my attending's office to field a complaint from a resident--a resident--who thought pumping around other people was inappropriate. It wasn't that the pump was distracting (most of the residents didn't even realize I was using it) or that I was being "immodest" (fully covered! back corner of the room!). This complaint centered around the idea that pumping was happening in the presence of other people.

I was shocked. And then I was annoyed. And then I went to discuss it with our dean, because really, folks, if we can't handle this in our own space, then we had better not be counseling our patients that they can find a way to do it. I also wanted to find out how my institution's policies applied to situations like these.

What I discovered was this: the employee breastfeeding policy did not cover students because we were not technically employees. The Virginia state law that permits breastfeeding in public places also did not apply because "the public" could not technically walk into our lecture hall in the hospital.

I wasn't comfortable with that.

It's incredibly important to have tangible protections in situations like these for medical students, who are on the wrong end of a rather large power dynamic. It's hard to ask an attending who will be writing a performance review for your residency applications for 15-20 minutes "off" every four hours. It's not unreasonable to think that some attendings might view this as a lack of commitment--regardless of the validity of that view--and it's something I worried about every time I had to make the request. I had the benefit of working out some of the kinks of self-advocacy in my prior career, but not all students would be comfortable advocating for these needs. Some might instead just choose to stop breastfeeding, which is not ideal for mom, baby, or our overall progress toward supporting breastfeeding as a medical community and a society.

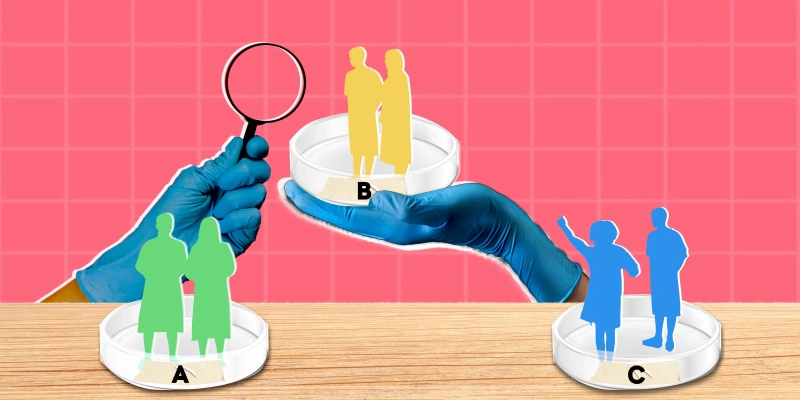

One of the ways to mitigate this power dynamic is to create a policy that clearly defines the standards and expectations for both sides so that students have top-cover for their requests and supervisors are not struggling to come up with accommodations. We set out to create such a policy with input from other students, administrators, and local breastfeeding advocates. The result is neither perfect nor comprehensive, but it's a good start. It clearly demonstrates that the organization is aware of and values the needs of breastfeeding students; it sets a good precedent for behaviors that we recommend to our own patients; and it sends a message that family and career can co-exist from the ground up.

I would strongly encourage other medical organizations to evaluate their own breastfeeding policies. Make sure you are covering your students and trainees, and show them how to lead by example.

We can, and should, do better for our profession and our patients, starting from the beginning.

Amy Blake is an internal medicine resident and a 2018-2019 Doximity Author. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization with which she is or has been affiliated.