The turbulence awakened me first.

I was flying home for the December holidays, and I had just settled into a nap when the airplane hit an air pocket and started shaking. Then came the call over the intercom.

“Is there a doctor on board?”

As a fourth-year medical student, I am months away from receiving my medical degree, but I still thought I could perhaps be of assistance. I turned in my seat, and about five rows behind me, I saw flight attendants lifting an unconscious man who looked to be in his mid 60s onto the floor of the galley.

I hurried over, and I rapidly assessed the situation. I felt the man for a pulse. He had none. His heart was not beating either. It appeared that he had gone into cardiac arrest.

“Let’s start CPR,” I told the flight attendants. I held a frazzled conference with the man’s son. Apparently, the man had slumped suddenly, without warning. He had diet-controlled diabetes but no other known medical conditions.

Sensing the commotion, two other passengers joined me, a gynecologist and a nurse practitioner. I told them what I had learned, and they agreed that cardiac arrest was the most likely cause of the man’s condition.

The three of us, along with flight attendants, rendered aid for the next 45 minutes. We checked the man’s blood glucose and administered epinephrine. We continued first aid as the airplane continued to whir and careen through the air.

With the gynecologist and NP in charge of the patient’s direct treatment, it became my primary responsibility to communicate with the flight attendants, the cockpit crew, as well as ground control about the situation. We collectively decided that an emergency landing would be futile based on the time needed to reach the nearest airport and land.

After 45 minutes, despite our best efforts, the patient’s heart had still not restarted.

“We should probably call it,” the gynecologist flatly stated, and everyone agreed. We held a brief moment of silence for the man, and then the flight crew moved him into a body bag.

Returning to my seat, I realized that the vast majority of passengers had no idea that a man had just died on board. I replayed the events in my head, wondering if anything could have been done differently.

When I told my family about what had transpired on board, they were encouraging and kind.

“I would much rather be helped by a medical student than someone without any medical knowledge,” my father consoled me. “You did your best.”

But with a sense of regret, I thought about how medical school did not fully prepare me to render aid to a passenger on an airplane. Instead, my assessment of the situation came from an app, which one of my teachers had suggested in my second year of medical school.

Called AirRx, the app covers several common in-flight medical emergencies and provides treatment algorithms for each emergency. I had read through the app a few times in the past couple of years, and I relied upon that knowledge during my December flight.

In medical school, we are superbly prepared to work with patients in the hospital or the clinic. Had the man on the airplane gone into cardiac arrest in a hospital, I would have known exactly what initial steps to take. Outside of a health care setting, however, I had little formal training in how to assist in a medical emergency.

Some may argue that medical emergencies on airplanes are rare, but they are more common than many may believe. A 2013 paper in The New England Journal of Medicine found that 1-in-600 flights will see a medical emergency on board. As a point of reference, the FAA states that it handles 45,000 flights every day. The data are clear, therefore, that we cannot reasonably expect all medical emergencies to occur near a hospital.

Yet my medical school has no required courses regarding medicine outside the hospital or clinic. In fact, as part of our standard medical training curriculum, my classmates and I were only instructed to complete Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) training this winter, a month after my experience on the airplane.

Health care providers are seen as experts in their field, not just in the hospital but outside it as well. We should be trained to provide health care regardless of the setting. Good Samaritan laws usually protect clinicians from litigation when providing care outside a hospital, and our training should reflect this responsibility and privilege. A course in “street” or “field” medicine should be required or integrated with existing courses in family or internal medicine.

Teaching should account for not only what to do in the hospital but also how to address medical emergencies when a hospital is far away. And ACLS training should be provided to all students early in their education.

I was disappointed that during the in-flight emergency that I experienced, I relied more on what I had learned from an app than from what I had learned in 3.5 years of medical school. What is the purpose of a medical school education if it does not enable us to instantly render aid during medical emergencies, regardless of location? After all, emergencies can occur anywhere. It is our duty as health care providers to be prepared.

If you've been part of a medical emergency outside of the hospital or clinic, share in the comments how you improvised care.

Sathvik Namburar, originally from Duluth, GA and a graduate of Johns Hopkins University, is currently a medical student at Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH. His writing has been published in USA Today, Boston Globe, and Baltimore Sun, among other publications. His interests include public health policy and health care equity, as well as global health. He is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

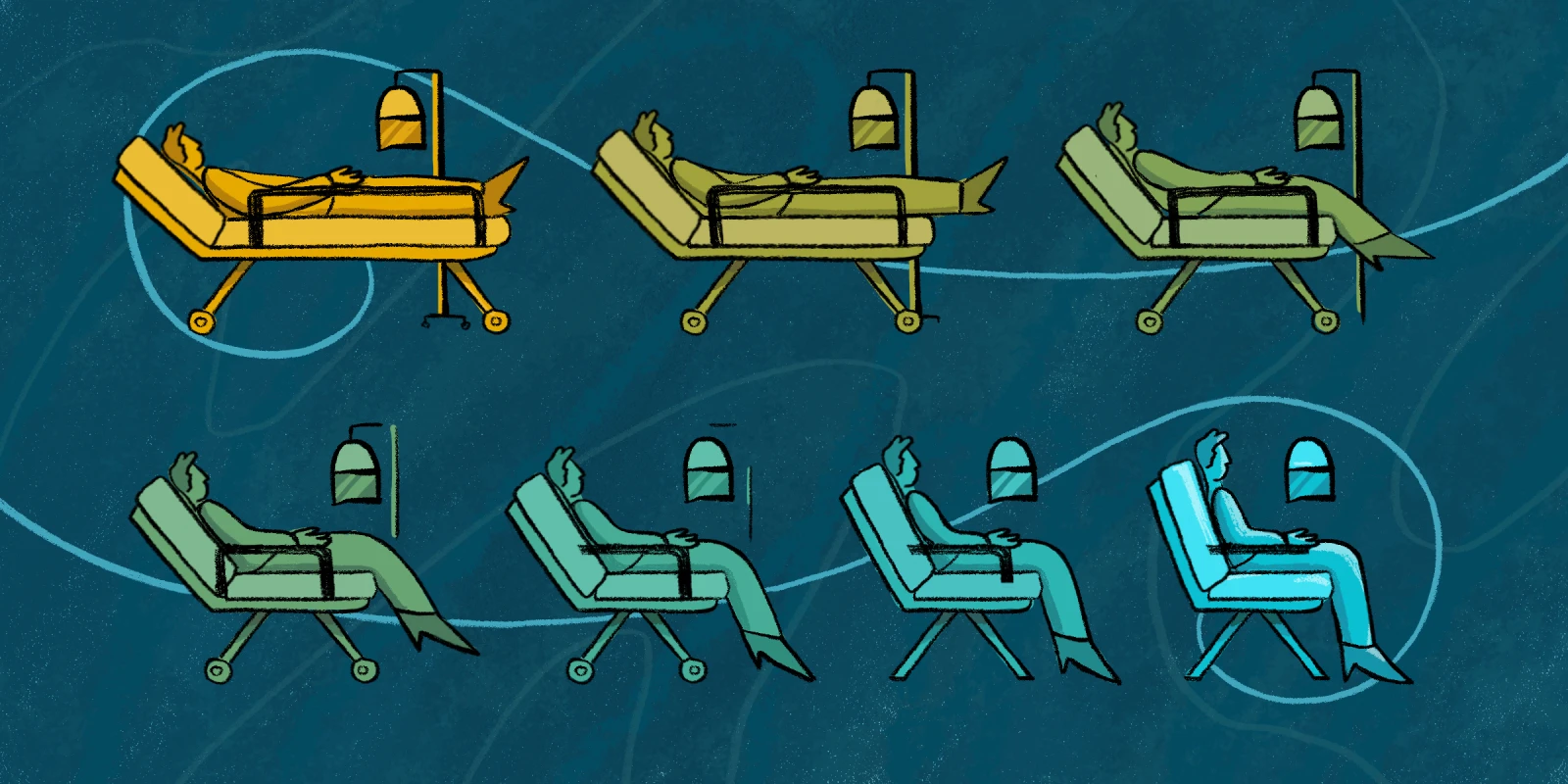

Illustration by Diana Connolly