This is part of the Medical Humanities Series on Op-Med, which showcases creative work by our members. Do you have a poem, short story, creative nonfiction or visual art piece related to medicine that you’d like to share with the community? Send it to us here.

When the Algorithm Comes Alive

“Are you ready? This one is all yours.”

I nod. I want it to be. It’s my last day.

Remember:

Protect the perineum.

Hands on the head, push down. Shoulder. Pull up. Grab hips. Baby on the stomach. I chant. It’s a melody. It’s a prayer. It’s almost 6 a.m. It’s the 12th hour.

“No hand over hand. You got this. You’re scrubbed; I’m just here to watch.”

“Respire y puja. Uno, dos…” Baby out already. Cord is tangled around his neck. Unwrapped; baby on stomach. “Feliz cumpleaños Mateo.” I’m smiling. Mama is crying. Mateo is crying. Dad is beaming.

Clamp. Cord blood. Cord segment. Placenta out.

Woah, that’s a third degree.

It’s my fault. My forehead is damp. Uterine massage. Pit bolus.

“Estimated blood loss?”

I look down. “500, it’s still coming.”

I look up. She’s nauseous. She’s heaving. It’s my fault.

“Do we have the cart? Someone find me Methergine.”

I find my voice. “No. She’s preeclamptic.”

“Okay, restart Miso. Where is the rest of the team?”

“Shift change,” someone in the room replies.

“Damn it. Estimated blood loss?”

“EBL 950.” It’s my fault. She’s turning a sickly green. Her family is standing off to the side, anxious looks on their faces. It’s my fault.

“Prep the balloon. I am going to need your help with this.”

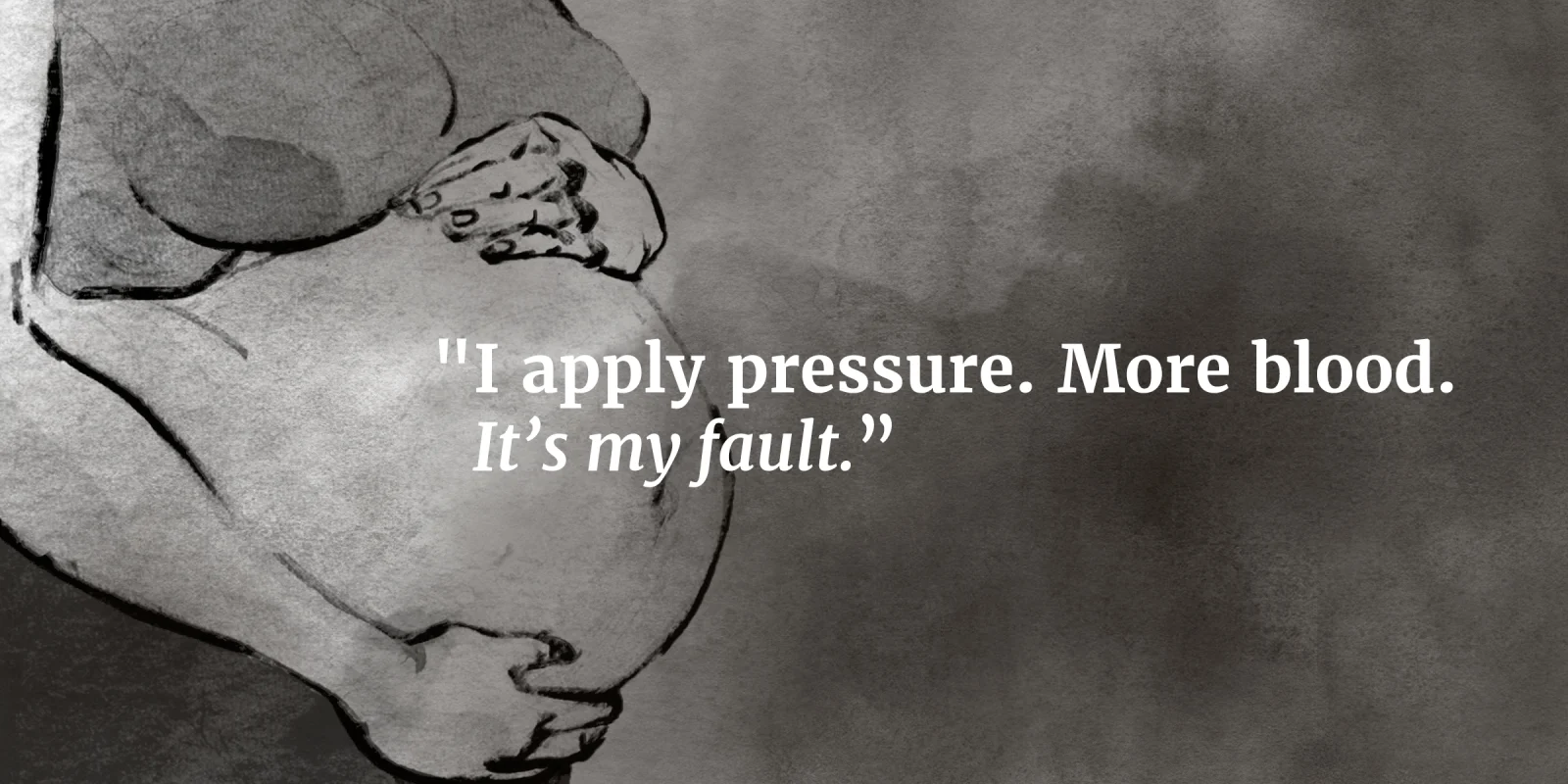

I nod. I’ve never done this before. My hands feel less nimble than usual. I apply pressure. More blood. It’s my fault.

“EBL?” someone in the room asks.

“1010, balloon in.” More pressure, nothing comes out. I breathe.

We explain.

We’re walking back.

“None of that was your fault. Atony happens. You did good. Go home.”

I nod. It’s my responsibility. I’m overwhelmed with guilt.

I'm in the car and the flood of tears finally kicks in. It’s not your fault.

I'm home. So drained, I crash. I dream of her.

A beeping wakes me. I check my phone — 4 p.m. An email notification.

“Our patient is stable, she and the baby are doing great. Atony, like suspected. Thanks for all your help. Get some rest.”

I close my eyes and I’m crying again. She’s okay. It’s not your fault.

I am lulled back asleep. I dream of her.

An Interview with the Author

What inspired you to write this piece?

My inspiration for this piece came from the wards of my third-year rotations and my medical humanities program. We were required to keep a bimonthly journal of reflections, which aided in helping me process moments such as the one discussed in this piece. Situations like these feel too large and emotionally charged to dissect in the moment, but are important to cross-examine and learn from for continued growth as a future clinician.

How long have you been writing? What got you started?

I have been writing both poetry and prose as a hobby since I was in middle school. However, during my college years, I began to use writing as an outlet for understanding the world around me. As such, reading and writing, both prose and poetry, are essential parts of my identity.

Why did you choose prose poetry? What interests you about it?

I find comfort in the anonymity and descriptive vagueness afforded by poetry. Although I enjoy writing prose and short stories, I find myself most honest and vulnerable when utilizing poetry as the vehicle for connection.

How does this piece relate to your medical practice?

I believe in writing as a form of processing and healing. I am most vulnerable in poetry and prose, and writing gives me the tools and courage to express and understand the emotionally taxing job and responsibility of being a physician. As someone going into a surgical subspecialty, I find that the conversation of narrative as a form of healing often excludes surgeons; I find that this actually stunts the growth of a clinician and can even lead to detachment and loss of empathy for our patients. I would not only like to continue my practice of narrative medicine, but also, encourage my future peers to do the same.

May Ameri is a medical student at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. She is pursuing a medical humanities concentration and is passionate about narrative medicine as a vehicle for connecting with patients and preventing burnout. She is passionate about bridging the gap between medicine, policy, and advocacy. As an immigrant and previous Albert Schweitzer Fellow and Graduate Archer Fellow, Ameri encountered the complex health disparities that affect minorities. Her goal is to work toward reducing health disparities faced by her local immigrant and refugee community. She hopes to become a policy advisor on issues of health care disparities and serve as a strong advocate for marginalized patients.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz