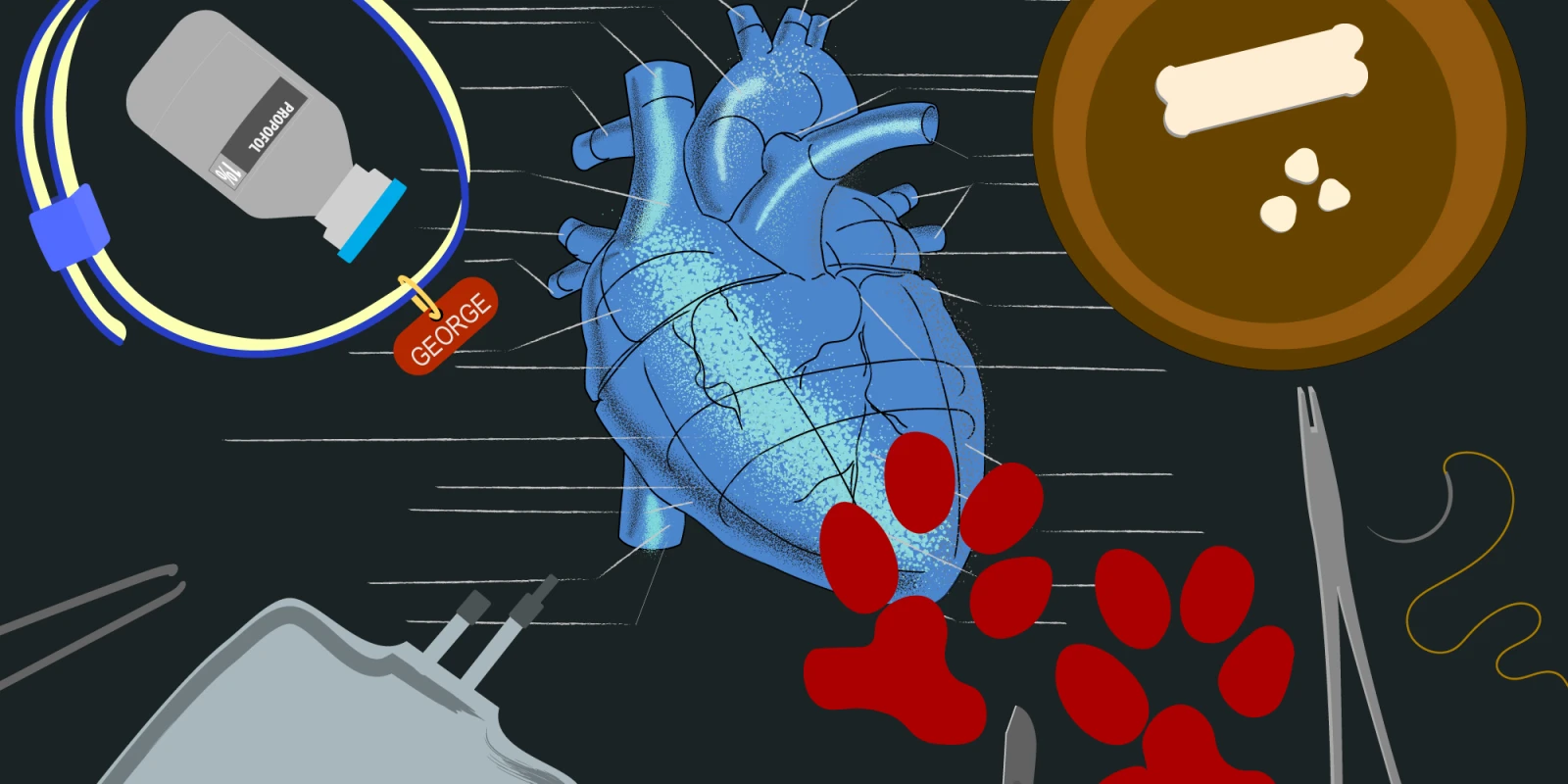

“When he wakes, come to my office and we’ll debrief your case.” Dr. Lust must have read the confusion on my face because he continued as he walked away. “You put him to sleep didn’t you? That means you stay until he wakes up. Come find me then.” I slid down the wall of the kennel to sit next to George with nothing but my own thoughts and the slow soft sounds of his breaths to keep me company. The relief of being off my feet was diminished by an overwhelming sense of disappointment. Dr. Lust was right. I was the one who pushed the Propofol, intubated, and anesthetized George. I was also the one whose surgical inexperience had kept him under for nine hours in an operation that should have taken only three. Now, all I could do was wait to see if he would survive. Over the years, I had eagerly anticipated my first time as the surgeon in the operating room. But I never imagined the intense anticipation of waiting for my first patient to waken from the anesthesia. What had I gotten myself into?

The sounds of voices approaching down the hall shook me from my reverie and I briskly swiped the corners of my eyes in hopes that I wouldn’t be caught in a moment of vulnerability. It was Anita, one of the many staff members in the Department of Comparative Medicine who were sacrificing their evenings and weekends to help me complete this daunting project. She smiled kindly as she handed me a heating blanket to add to the throne I had created for George in our makeshift PACU. Her expression was one of understanding. “How many students has she seen experience this?” I wondered.

I have always considered animal research one of the “necessary evils” required for the advancement of medicine. For generations, medical students and residents have taken advantage of these research opportunities to advance their procedural skills; maximizing our experiences to ensure that these precious creatures do not give their lives in vain. I tried to remind myself of this, but as I looked over at George, my heart ached for him. In the weeks leading up to their surgeries, I would visit with them; peanut butter treats in hand. Earning their trust so that it would be easier to work with them for ultrasound measurements in the days following the surgery. I named George and his two kennel companions, Ginny and Fred, after the Weasley family from the Harry Potter series. I had truly connected with each of my patients and now I was second-guessing my decision to take their lives in my hands.

Not too long ago, I was an eager first year medical student standing in the office of my favorite physiology professor, Dr. Lust, asking about research opportunities. It was his lectures that first sparked my interest in cardiovascular science and he was always excited to work with students. After speaking for a while he suggested a project he had been hoping to start for a few years, but he had been waiting for the right student. I accepted immediately. I had no idea how life-changing this experience would turn out to be. Soon I began my summer research project, hopeful that I may get to practice suturing and tying knots. One short month later, I was standing across from Dr. Lust at the operating table, scalpel in hand, waiting to time out. To this day, I am still unsure whether it was the weight of my borrowed loops or the responsibility as lead surgeon that rested so heavily on my shoulders. The saphenous vein dissection had gone smoothly as tissue planes that had eluded me so frustratingly in Gross Anatomy now revealed themselves at the slightest spread of my Metzenbaum scissors. Despite practicing relentlessly in the preceding weeks on synthetic grafts, I was still unprepared for the incredibly tedious end-to-side anastomoses. The 8-0 Prolene felt as delicate as a spider’s web in my hands and Dr. Lust frequently reminded me to use my loops for assistance. Suddenly, a muffled cough brought me out of my head and back to reality. George lifted his head to look at me. The wait was over and I suddenly felt as if I could breathe again.

Over the next ten days the operations became easier. The instruments began to feel more natural in my hands; my actions became more confident and deliberate. As my operating times improved, the time my patients spent in the PACU decreased. Despite my growing confidence in the OR, I still felt the enormous weight of responsibility in the PACU every evening. By the last day, I had successfully completed twelve bilateral canine carotid artery bypass operations, one emergent graft revision, twelve graft harvests, and countless ultrasound assessments. This research project was a wonderful surgical opportunity, but I will never forget the intense connections made with my patients before and after their procedures. As I continue to interview for residency positions in Anesthesiology, I am always thrilled to share this deeply personal and powerful experience. It has shaped who I am both personally and professionally and I am so grateful to have had this incredible opportunity.

Katherine Barefoot is currently a first year anesthesiology resident at the University of Virginia. On her days off she enjoys cooking, knitting, and watching movies with her fiancé and their dog Lucy. For her, being a physician is a privilege and she is honored to care for her patients no matter the shape or species.