Recently, several prominent dictionaries released their “word of the year.” For 2022, Merriam-Webster’s selection was “gaslighting,” while Collins English Dictionary chose “permacrisis.” If I were asked instead to choose a word of the year within health care, there would be no ambiguity. The word of the past 12 months would have to be burnout.

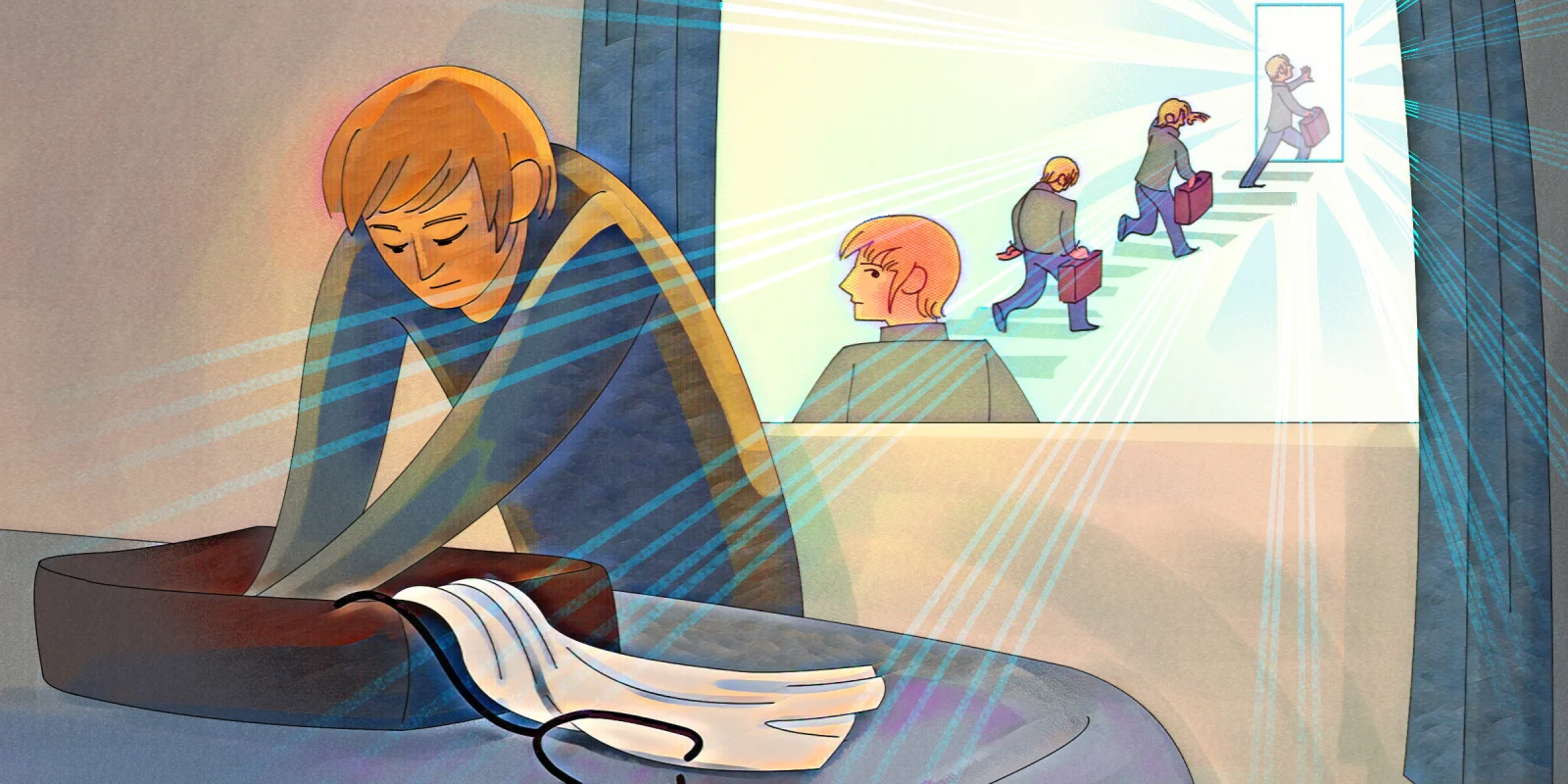

Much has been written about the causes and potential cures of burnout among health care professionals, but nothing fully encompasses the stories I hear in my office. In fact, many are struggling most with an identity crisis. They describe their dismay as they watch their energy, enthusiasm, and compassion decline with each passing year. After chasing any number of opportunities in search of happiness, including academic titles, publications, and increased salaries, they enter my office feeling lost, untethered, burned out.

Dr. Parker Palmer describes in his book, “Let Your Life Speak,” how taking the path he thought he should pursue, guided by altruism, led to burnout and painful self-exploration. He learns, “We can learn as much about our nature by running into our limits as by experiencing our potentials.”

Of course, this is true. Looking back over my life, periods when I headed off confidently in the wrong direction comprise a significant portion of my winding career path. But in the culture of medical training, we are socialized to hide our indecision, promote our strengths, and perpetually chase that gold star until we’ve “made it.” In other words, we need to make sure that everyone views us as truly special.

Arthur Brooks, a Harvard social scientist and regular contributor to The Atlantic with his “How to Build a Life” column, in “From Strength to Strength,” writes, “I’m going to ask you not to deny your weaknesses but rather to embrace them defenselessly. To let go of some things in your life that you worked hard for — but that are now holding you back. To adopt parts of life that will make you happy, even if they don’t make you special.”

At the start of my own career, I believed I would be happiest in an academic environment, filling my CV with invited lectures. Eventually, though, this path lost its luster. I didn’t feel as proud of myself or my work as I expected, and my parents, to their credit, didn’t treat me any differently with new titles next to my name. They just hoped I would take time off to visit so they could hug their grandchildren.

Finally, I left full-time academia and the many remarkable people there. It felt less like a triumph than a self-reckoning.

Then one of my dearest friends, John, a brilliant psychiatrist, husband, and father of a beautiful daughter, died of brain cancer.

As I prepared to memorialize him in Los Angeles, the pandemic hit, and the gathering was postponed into an unknown future. I tried to focus on shifting my practice and navigating unexpected home schooling, while I grieved this momentous loss, but staying busy just didn’t help anymore.

I was forced to reconsider everything, and it was one of the most difficult periods of my life.

I knew what I had to do with the blessing of the life I had been given, unlike my dear friend. I needed to find a way to help more people, to represent his voice and his strong belief in the importance of dignity for each patient seeking my help.

What I’ve learned in the years since has provided valuable lessons I share with each physician in my practice.

First, the need to always feel special, important, or see ourselves as someone held apart from others due to the title of physician, keeps us trapped in a never-ending cycle of striving and fearfully avoiding failure.

Second, we need to relinquish the idea of what a “real doctor” would do in any particular situation. The training we’ve received, and the awareness of the human condition it provides, could be utilized in novel ways that would be better aligned with our gifts. At the same time, we are allowed to limit, without guilt, roles and environments that we find harmful to our health and well-being.

The writer and theologian Frederick Buechner defines vocation as “the place where your deep gladness meets the world’s deep need.” There are so many ways that we as trained physicians can change the lives of the people in our orbit and far beyond. The way you choose to meet the world’s needs may be something unexpected.

“Our strongest gifts are usually those we are barely aware of possessing,” Dr. Palmer writes. For me, I could see, when I actually allowed myself to look, that some of the most engaging and meaningful times in my life involved creative outlets with other committed individuals, especially performing as an actor and singer. Instead of ignoring the longing I felt to travel back in time to those exciting moments, I started planning ways to bring more creativity into the present.

This has led me to begin writing as well as creating my podcast, which started as a way to connect with individuals throughout the world who are committed to making positive change. I am able to perform again, but in a way that aligns with my goals and training.

Our time and investment in becoming physicians do not need to trap us in an endless cycle of burnout and dissatisfaction. Yes, it takes courage to shift energy from what was expected toward what is desired. However, meaningful change is best created by individuals pursuing work they enjoy, aligned with their skills and interests, to the very best of their ability. See what happens when you allow yourself to explore the possibilities.

What changes do you look forward to making in your life and career? Share in the comments.

Dr. Jennifer Reid, M.D. is a board-certified psychiatrist, specializing in anxiety, insomnia, and interpersonal psychotherapy. She is also an educator in her role as Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She practices in Philadelphia, PA, and writes and podcasts at www.thereflectivedoc.com.

Illustration by April Brust