At the recent 60th Annual Scientific Meeting for the American Headache Society, it was truly an honor to receive the Seymour Solomon Award, in honor of a beloved colleague: Dr. Solomon, now in his nineties, continues to teach residents and fellows at the Montefiore Headache Center and is a true inspiration and leader in our field.

My talk, “Under Pressure,” focused primarily on the diagnosis of spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) or “low pressure headache.” SIH nearly always rises from a defect in the spinal dura, which creates a spinal fluid leak. The condition is relatively easy to diagnose when a patient has typical symptoms and brain MRI findings, but about 25% of people with SIH have a normal brain MRI. There is also a wide variety of symptoms other than headache that patients may experience. Hence, the diagnosis is often elusive and patients may be misdiagnosed for years or decades, while being treated for conditions they don’t have with medications that don’t work.

At its worst, people are completely bedridden from SIH. Throughout the years, I realized that SIH is much more common than we realize and that every provider treating headache probably has patients with SIH in their practice that have not yet been identified. (Including me!)

Therefore, it is up to all of us to be detectives because the diagnosis is suspected almost entirely on the patient’s history.

The headache of SIH is typically absent or milder in the morning and develops or worsens as the day progresses. The other common scenario is improvement (sometimes resolution) when lying flat and worsening in the upright posture. It is not enough to ask the patient whether their headache is better in the morning because it sometimes starts immediately after arising from bed; we need to know how they feel upon awakening before they get out of bed.

Further, the pain can be located anywhere in the head and may also involve the face, teeth and neck. It can be constant or intermittent, unilateral or bilateral. Many patients have typical migraine-associated symptoms: sensitivity to light (sometimes very severe), noise and odors, nausea and vomiting. SIH should always be considered in patients with New Daily Persistent Headache (it started one day and never resolved), initial “thunderclap” (sudden, severe) onset, or in patients who have headaches are refractory to “everything.” The pain often awakens people from sleep and worsens with physical activity and Valsalva maneuvers (which includes coughing, sneezing, straining, laughing, lifting, bending and sexual activity). Caffeine sometimes helps and the symptoms may improve at high altitude.

Other common symptoms that accompany the SIH headache are tinnitus, hearing loss, shoulder pain, pain between the shoulder blades and in the upper back (“coat hanger” headache), imbalance, dizziness, and cognitive dysfunction. Less frequently, movement disorders (hypokinetic or hyperkinetic), altered taste sensation, blurred vision, diplopia and galactorrhea occur. Patients may come to the hospital in coma with subdural fluid collections or intracranial hemorrhage. Many of these symptoms overlap with primary headache disorders but others are unusual, and not typically ones that we ask about in a headache practice.

Although it is called “spontaneous” intracranial hypotension, people can often identify a precipitating event. However, it can be very trivial trauma which was not even realized as causative by the patient. I ask my patients about any preceding injury (car accident, fall); an illness associated with protracted coughing or vomiting; heavy lifting (moving, starting a new exercise program, weight lifting); riding a roller coaster or similar amusement park ride; chiropractic manipulation; and vigorous athletic activities such as those which involve twisting (golf, tennis, canoeing, kayaking, yoga).

Sometimes the leaks are iatrogenic from a previous lumbar puncture, myelogram, spinal anesthesia, epidural anesthesia or blocks (which inadvertently punctured the dura) or previous spine surgery. Herniated or calcified disks can tear the dura and bariatric surgery may be a risk factor.

One of the best-known risk factors for developing SIH is a joint hypermobility syndrome, such as Ehlers Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome. However, many patients with joint hypermobility have never been diagnosed with a particular disorder. Asking patients if they are “double jointed” or “super flexible” is important, even dating back to childhood (most of us become less flexible as we age!). Patients who participated in gymnastics, ballet, tumbling or cheerleading are prime candidates. People with joint hypermobility are usually very good at yoga. It is theorized that joint hypermobility is associated with more fragile dura that is prone to tear with activities that would generally not affect the average person. Ask about a family history of joint hypermobility, arterial dissection, retinal detachment at a young age and non-rheumatic valvular heart disease. There are validated scales to diagnosed joint hypermobility to assess it in the office. Patients may be slim with long fingers and slender necks but SIH can affect people with any type of body habitus.

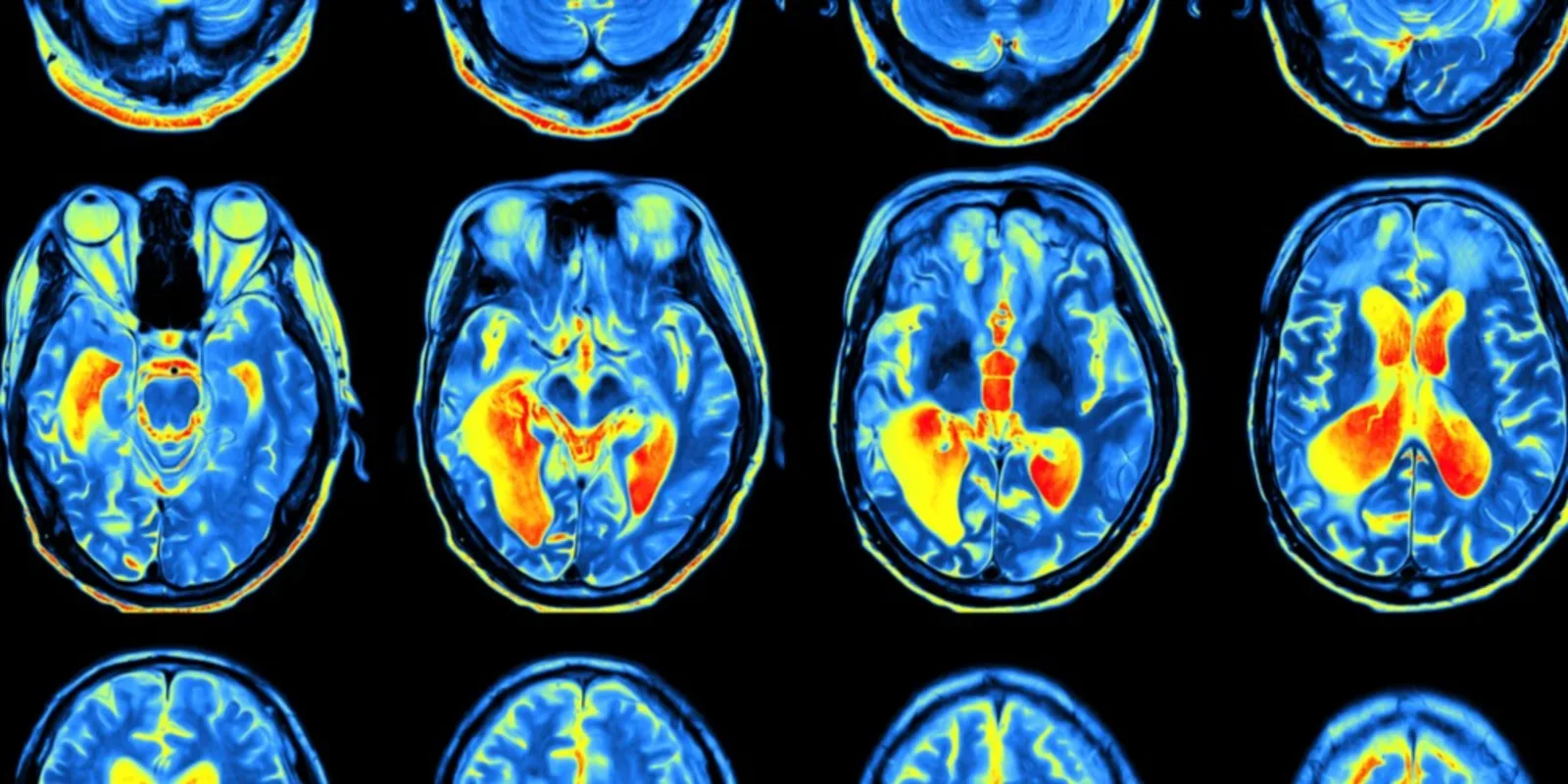

The diagnosis is supported by an abnormal MRI with contrast showing brain sag and meningeal enhancement. The treatment is a team approach and requires neuroradiologists and neurosurgeons who have expertise in SIH. There is no agreed-upon management strategy. Non-invasive treatments include bedrest, caffeine or other xanthines, an abdominal binder, elevating the foot of the bed, hydration, a course of steroids and greater occipital nerve blocks.

The longer the duration of symptoms, however, the less likely that these methods will be effective. CT myelography, MR myelography and digital subtraction myelography may be used to try to identify to site of the leak, which ultimately cannot be found in about 50% of patients. These studies may show other changes in the spine that give clues about where the leak is arising, such as peri-neural root sleeve cysts. If a leak or potential leak is found, targeted blood patches using fibrin sealant (performed with CT guidance) are employed. Others prefer to forego myelography initially and try high-volume lumbar epidural blood patches which have about a 33% success rate. Surgical repair is sometimes needed.

As challenging as the diagnosis is, the treatment can be equally tricky, requiring multiple procedures with suboptimal or temporary improvement. On the other end of the spectrum, some patients develop increased intracranial pressure after the spinal leak is sealed. And to further complicate the issue, patients with intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri or idiopathic intracranial hypertension) can self-compress through a spinal leak so they end up trying to balance their spinal fluid pressure having both conditions!

I hope that these strategies are useful and encourage my colleagues to put on their detective hats because these patients are in our practices and need our help!

Dr. Deborah Friedman is a board-certified neurologist and specialist in a Neuro-Ophthalmology and Headache Medicine. She is the founding director of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Headache and Facial Pain Program, as well as a professor of Neurology & Neurotherapeutics and Ophthalmology at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

She was a past president and board chair of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society and currently is a board member of the American Headache Society.