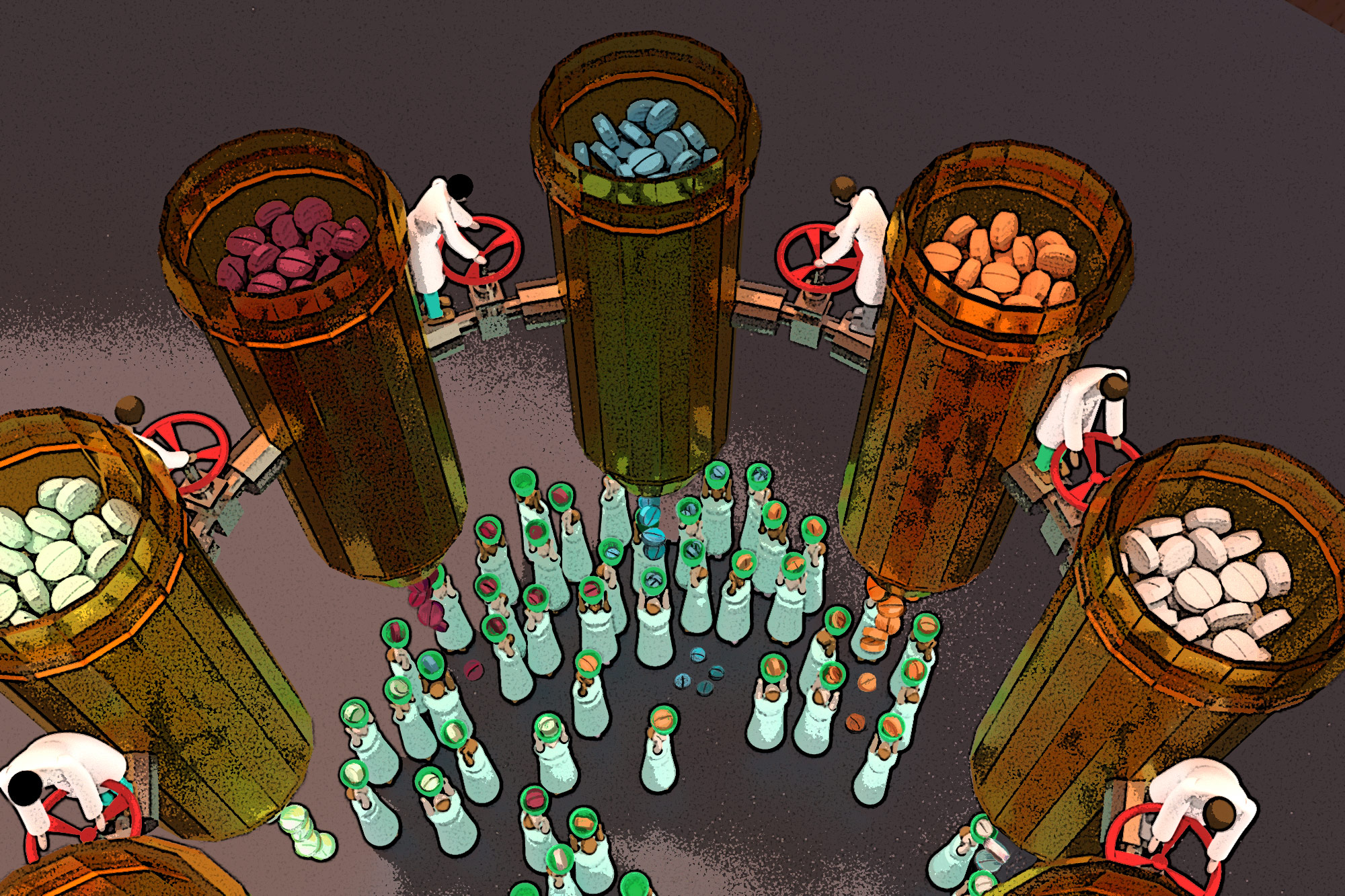

Unlike other drug crises, 80% of opioid addiction starts with a pill prescribed by a physician or dentist. I was trained in the late 1990s, which was the perfect storm for opioids: humanitarian good will, the desire to correct pain treatment inequities (that persist), the rise of the HMO and “patient as customer,” and a giant push from pharma overtly and covertly teaching that “opioids aren’t addictive if you’re really in pain.”

Unlike other drug crises, 80% of opioid addiction starts with a pill prescribed by a physician or dentist. I was trained in the late 1990s, which was the perfect storm for opioids: humanitarian good will, the desire to correct pain treatment inequities (that persist), the rise of the HMO and “patient as customer,” and a giant push from pharma overtly and covertly teaching that “opioids aren’t addictive if you’re really in pain.”

We know more now. We know 10-15% of people are susceptible to addictive highs beyond pain relief due to genetic metabolism speed. We know 5% of people prescribed routine opioids are addicted within a year, tenfold the number who aren’t. Most importantly, we know that for most outpatient injuries and surgeries, opioids are inferior to over-the-counter (OTC) options. Considering risk, efficacy, and why we prescribe, it is time to wean off writing for opioids for acute minor outpatient pain.

What We Know About Risk

First, do no harm. As an extremely homogeneous procedure, oral surgery is a great model for pain relief research. A compelling argument that any exposure increases the risk of addiction comes from Schroeder et al., who recently reported that 5.8% of youth prescribed opioids for this procedure were diagnosed with Opioid Use Disorder within one year and of age-matched subjects without an opioid prescription, only 0.4%. The risk factor most associated with opioid addiction was that someone prescribed them opioids. As opioids are prescribed 37 times more in the U.S. than England for the same procedures, this risk seems unnecessary.

Even routine post-surgical home opioids carry risk. Addiction was 5.1 times higher after knee replacement, 3.6 times higher after open gallbladder surgery, and 1.28 times higher after a C-section. Typically, more opioids are prescribed for knee replacements than gallbladders and C-sections. If addiction were a moral failing, the temporal correlation is odd. Instead, it's a simple linear relationship — the more opioids prescribed, the greater the chance of addiction.

Duration of Opioid Prescription and Addiction

Image from the CDC

In addition to inherent tolerance, a complex genetic array of drug metabolism can make opioids ineffective, or hyper-intense. While I was grateful for codeine and fentanyl after various fracture-associated misadventures, home pills left me foggy and nauseated. In contrast, “Percocet made me feel great!” said a friend in addiction recovery. “The drugs made me feel energized, happy, and totally unselfconscious. As they hit, they made me feel cool.”

Ultra-rapid metabolizers get a rush; ultra-slow metabolizers get nauseated, or don’t even get pain relief. Without insight to our patients' genetics, we’re introducing some to a craving they would have never had.

What We Now Know About Efficacy

Potentially, because of metabolic variation, many studies don’t show a benefit for home opioids. For wisdom teeth extractions, multiple studies showed ibuprofen superior to Tylenol with codeine.

For pediatric fractures, ibuprofen was at least as good as opioids for pain relief. For carpal tunnel release, hand surgeries, and general surgeries from cholecystectomy to robotic prostatectomy, over-the-counter pain medication was sufficient or superior. The only differences were opioid side effects.

With the exception of the pediatric fracture studies, most of this research was published in the last two years. Few family practitioners, emergency doctors, or surgeons would have reason to know this new data. Now that we know, what do we do?

Why Do We Write For Opioids Anyway?

In one of the earliest examples of big data, Porter and Jick (1980) published a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine evaluating addiction to in-hospital opioids. The article, “Addiction Rare In Patients Treated With Narcotics,” claimed that their data showed addiction at discharge was fractional. That’s important: AT DISCHARGE. There was no follow-up. This “landmark study” was cited to assuage addiction fears when Purdue pharma launched OxyContin. It was a part of the PowerPoint slides we absorbed with our lasagna lunches post-call.

In the early 2000s, scripts for outpatient opioids soared. Writing for oxycodone showed you cared and believed patients hurt. Soon, patients demanded “the good stuff,” and the regulatory hassle of writing refill prescriptions pushed toward bigger numbers of pills. Even when unused, excess just-in-case pills ended up in medicine cabinets. Over 80% of opioids used recreationally were shared by friends or family or directly prescribed and saved.

How Do We Stop?

While there are some surveys of prescribing practices and use, the actual opioid need for various acute maladies is undetermined. As opioid-sparing research proliferates, a few models are emerging. Hallway et al. found that the most important part of opioid reduction came from coaching. Priming patients that staggered OTC medication was usually sufficient, worked. Most patients used either all or none of a 5-tabled “rescue” prescription. (To avoid the implied efficacy of rescue, perhaps a “Three to Try or Throw” or “Four to Fill or Flush” would be better. And yes, the FDA advocates flushing.)

Understanding the expected intensity and duration of pain and how to plan in advance, gives patients control. An Opioid-Free Pain Plan includes advocating for long acting lidocaine, priming with anti-inflammatory magnesium, and planning for distraction, social interaction, and pleasant surprises before surgery. After surgery or injury, optimizing OTC medication, using ice and specific inhibitory frequencies of mechanical massage, and supporting sleep is critical. Above all, planning for pain emphasizes that pain is expected yet manageable.

Image from VibraCool

Going cold turkey on the prescription habit will be hard. In Japan, they don’t give home opioids for knee surgery – but they don’t have 23-hour discharge pressure. A dose or two of opioids could help some patients sleep past their kidney stone, hip, or arthroscopy once discharged, or keep the 18% who AREN’T satisfied with opioid-free after orthopedic procedures mollified while a new norm settles in. Some patients can’t take ibuprofen. Sometimes there’s no time to coach, plan, or discuss the virtues of proven alternative therapies. Sometimes your patient is the board chairman’s relative.

In the scrum of assigning blame, many fault physicians. The valid defenses of a decade ago are no longer true. We do know. We must do no harm. The time for acute outpatient opioid prescribing – for fractures, for dental work, for hand, gallbladder, and so many more surgeries and injuries – is over.

Dr. Amy Baxter practiced Pediatric Emergency Medicine from 2000 – 2016. She researches and writes on pain management, invented the external neuromodulatory devices BuzzyHelps and VibraCool, is the CEO of Pain Care Labs and Clinical Associate Professor (affiliate) at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz