I’ve been consenting patients for four years in residency training now: consent to transfuse blood products, consent to operate, consent to place an invasive monitoring line. In addition to the purported benefits, I am required to discuss the known risks and alternatives — but honestly, I wouldn’t be trying to obtain their consent if I didn’t also believe the benefit outweighed the risk of the intended procedure. And in general, patients agree.

This year, I had to learn a new type of consent. I needed to consent a patient for permission to conduct research. The same information is still given: what's going to happen, what are the possible risks and benefits, what are the alternatives. But one stark difference is that the benefit, depending on the research, may be of no value to the specific patient. I was assisting a colleague who was studying workflow in the OR. My responsibilities were wholly limited to observing and taking notes on events; I didn’t have input or involvement in patient care. I was a mere fly on the wall.

From my perspective, my presence in the OR created minimal to no risk for the patient. The only potential benefit was that we hoped we'd learn something to improve OR workflow for surgical patients in the future. From the patient's perspective, however, I can see how the risk might seem more than minimal. No, no part of the study was intended or expected to cause harm. No, none of the information recorded would include identifiers linking the patient to the study. But still. There would be an extra person in the room — someone who was not a member of the care team, but who would still be able to see the patient in a vulnerable state, asleep under general anesthesia. Even with legal documents and verbiage confirming the absence of my clinical involvement as an observer, and restrictions on documenting identifiers, at the end of the day, I was still asking for a significant amount of trust. I was asking a patient to trust that I would follow through on everything promised and not post pictures on social media, or sell names/dates of birth/medical record numbers, or influence what the actual care team was doing.

For some patient populations, asking for trust is a big deal because that trust has already been broken. Even after the Nuremberg trials and the development of the 1947 Nuremberg Code on ethical principles guiding human experimentation, famous examples of unethical human experimentation still occurred. As recently as the 1990s, U.S. physicians were conducting antiretroviral drug trials in Zimbabwe with inadequate consent, leading to nearly 1,000 newborn babies contracting HIV/AIDS.

So, I worried a great deal about how to assuage fear, how to anticipate questions from the patient — even how I should introduce myself. And in this cloud of anxiety, while I was consenting my very first research patient, I ended up talking very fast, stumbling over phrasing while I flipped through the pages of the consent document. I could tell the patient was viewing me with suspicion. He turned me down.

Coincidentally, I had an appointment the next week to meet the investigator of a different study, not as a researcher but as a research subject! The stakes were different. I had already learned a great deal about the study, answered screening questions, and had chosen to attend the formal consent process to participate. I also had my own medical knowledge to protect me, so to speak. The investigator set herself up for success, too. She was friendly, spoke clearly, walked me through each paragraph of the consent form, and thoroughly answered all of my questions. Although her study asked for a great deal of commitment from me as a subject, I was happy to sign on.

I took my own experience as a research subject to heart. When it came time to consent patients for my own study on implementing a screening questionnaire, I emulated what I had learned. I took the time to establish a relationship first and foremost, sat down with the patient instead of standing, gave time to read, and time to ask questions. Even though the consent process took far longer than the actual research, I knew I would be compromising tenuous physician-patient relationships if I took any shortcuts. My research offered no direct benefit to patients and instead relied on their goodwill, so it was necessary that I demonstrate my own goodwill first. I have not had any patients turn me down since.

Ultimately, consenting for a lifesaving procedure and consenting for participation in clinical research boil down to the same conclusion. There must be a trusting relationship between consenter and consentee, with full transparency of the process, risks, benefits (if any), and alternatives. I think as doctors in the context of clinical care, we are often given a measure of implicit trust from patients. But for researchers, in a context wherein the patient is getting no benefit and is taking some personal risk, setting the stage for mutual trust and goodwill becomes vital.

What do you think are the cornerstones for trust-building in the doctor-patient relationship? Share your thoughts in the comments.

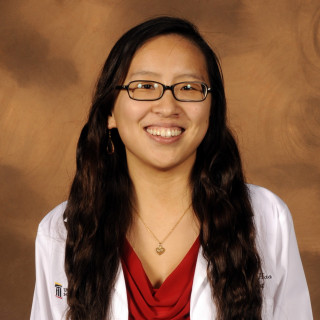

Scarlett Hao is a PGY-4 resident in general surgery at East Carolina University / Vidant Medical Center. She graduated from University of Maryland School of Medicine. She is pursuing a career in academic medicine and surgical oncology. Scarlett is a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust