On a rainy morning, I was driving to work on I-75 in Detroit, slightly irritated that my weather app hadn’t predicted it. The irony is that I actually like winter, snow, and the quiet they bring. What I don’t like is uncertainty, even though as an epileptologist I’m trained to accept it and eventually embrace it.

Uncertainty is at the core of epilepsy; it is one of the few diseases in medicine where the risk of recurrence is part of the definition itself. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management are fundamentally probabilistic. We start medications, maintain them, or stop them based on estimated seizure risk. We recommend patients stop driving, avoid certain activities, or accept lifestyle restrictions based on a balance of risk and benefit.

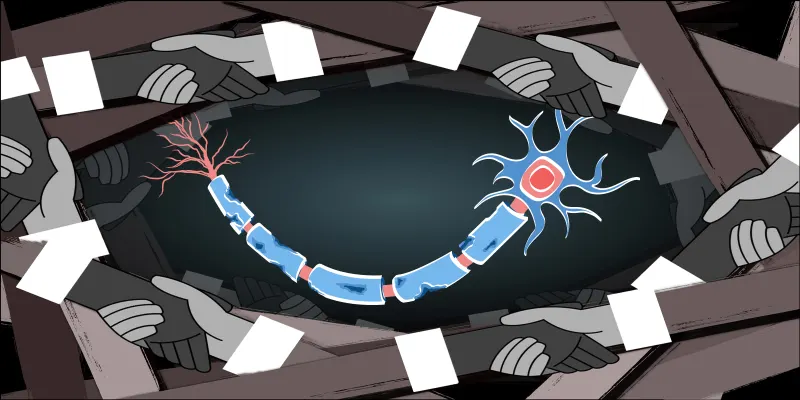

Epilepsy shares with cardiology a powerful investigative tool: electrophysiology. With electroencephalography (EEG), we can monitor brain activity with millisecond resolution. The goal is simple: capture brief moments when the brain misfires and hope the EEG detects them. When it does, a trained reviewer declares the EEG abnormal, signaling an increased risk of seizures in the appropriate clinical context.

This paradigm has naturally fueled interest in long-term EEG monitoring, not only for epilepsy diagnosis and seizure detection, but for short-horizon seizure forecasting (hours and days rather than months and years). Over time, enthusiasm has waxed and waned as technical hurdles have repeatedly surfaced: battery life, portability, signal degradation, and limited brain coverage. Systems have ranged from deeply invasive intracranial electrodes with multiyear recordings to subcutaneous devices to more recent ultra-portable scalp systems. Technological progress has steadily shrunk device size and footprint.

Technological progress opened the door to startups with well-intended engineers and entrepreneurs aiming to solve the “epilepsy” problem. Too often, these efforts proceed with minimal input from clinical epileptologists who understand where such devices fit in real patient care. The result is a mismatch between technological ambition and clinical reality.

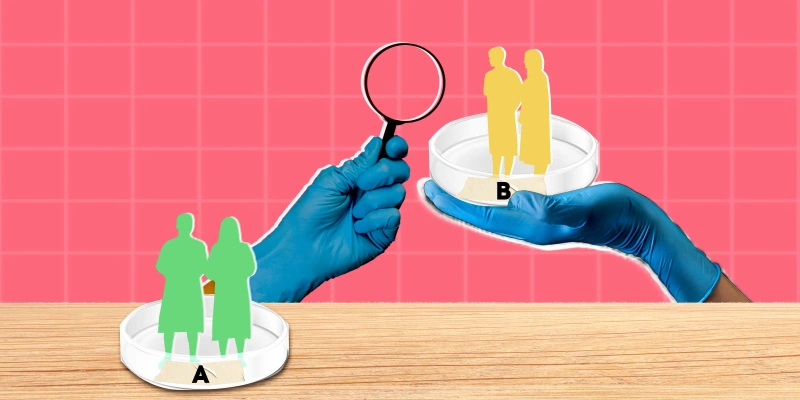

A major problem lies in the data used to train seizure forecasting algorithms. Much of it comes from epilepsy monitoring units (EMUs), specialized inpatient units where patients are admitted specifically to capture seizures. Antiseizure medication withdrawal is an essential step in most cases for a successful EMU stay. This creates a classic case of confounding.

Antiseizure medications are known to alter EEG signals. When medications are withdrawn, EEG patterns change. Algorithms trained on EMU data may mistakenly learn medication withdrawal effects as “pre-seizure” signals. In other words, the model is not detecting an impending seizure; it is detecting a pharmacologic state that does not exist in everyday life.

This is likely to affect many forecasting models trained on EMU data.

To support this concern, consider the responsive neurostimulation (RNS) system. It has been on the market for years, with many publications discussing seizure detection and forecasting. Yet despite prolonged real-world use and large datasets, there is no widely adopted or reliably successful short-horizon seizure forecasting system in clinical practice today.

Even weather forecasting remains imperfect despite centuries of scientific progress, dense sensor networks, and powerful computational models.

We do not have that level of understanding — or access — when it comes to the brain.

Seizure initiation arises from an interaction between complex neurobiology, human behavior, sleep, stress, medication adherence, and countless unmeasured variables. Our access to the brain is sparse, indirect, and often artificial. Expecting precise seizure forecasting under these constraints is a very optimistic but difficult-to-achieve goal.

Given current constraints and our incomplete understanding of seizure initiation, short-horizon forecasting will likely remain unreliable for many patients. Resources would be better invested in innovative epilepsy treatment options, refining long-term risk stratification, and developing decision-support tools that help patients and clinicians navigate uncertainty.

Waleed Abood, MD, is an epileptologist, assistant professor of neurology, and Epilepsy Fellowship Director at Wayne State University. He focuses on epilepsy, EEG, and how probability and uncertainty shape clinical decisions.

This article is part of the Medical Insights vertical on Op-Med, which features study breakdowns, resources, and insights from Doximity members on popular topics in medicine. Want to submit to Medical Insights? See our submission guidelines here; note that we are especially interested in articles covering oncology, dermatology, or rheumatology.

Image by Anton Vierietin / Shutterstock