I was unloading boxes moving in prior to starting residency when my mother, being the good Midwesterner that she is, walked over to my new next door neighbor to chat. The first thing she offered was that her daughter (me) was a doctor. As in, “Hello! Nice to meet you. My daughter is a doctor!” My dad did the same with the people across the street. I have also been introduced as a doctor to the church choir, most supermarket cashiers, gate agents at the airport, retirees on a river boat cruise, retirees on an ocean cruise, etc. My loving and supportive parents do it because they’re proud of me, but every time they do, it makes me cringe a little. Not because I am in any way shameful of my profession — it is the great privilege of my life to have a career as a physician — but because I know that all those strangers immediately have an assumed view of who I am.

Being a physician is certainly rarefied air. We are revered as intellectual and moral authorities in society, even with the concurrent distrust cultivated by years of unethical treatments and suspect financial relationships held by the few bad apples. We are the heroes of many a TV show and compensated generously. Legions of hopefuls study organic chemistry in hopes of earning entry into our ranks, only to be taken down at the knees by reactions I very much do not remember and certainly never use in my practice. Our position in health care is a kind of social currency manifested in small perks here and there. Late for an appointment? All is forgiven if you say surgery ran late. Flight home oversold? If you’re flying back to save lives there’s a pretty good chance you’ll retain your seat. On a smaller scale, I personally have been gifted a bottle of wine at hotel check-in and a complementary rental car upgrade when it came to light I was a doctor. (Note: these instances do not qualify as conflicts of interest, as I was sweaty and tired from leisure travel and also have no power to influence hospital purchasing behavior).

But these gifts are not free. They come with expectations about the kind of people we are, the values we have, the decisions we make. That mantle does not come off when you leave the hospital. You are always a physician, day or night, at work or home, active or retired. You are always a source of free advice to anyone you meet. I have been asked for advice on the workup of thyroid nodules in the middle of a visit in which I was the patient. (Short answer: Start with ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration based on TI-RADS grading, then refer or re-image based on the findings). On vacation, a Portuguese rock star/food tour leader asked me for professional voice advice and was not super happy with me when I said he should stop smoking. I have become insufferable when watching any kind of medically related entertainment, as I cannot stop myself from live fact-checking any “science-y” thing characters say. Being a doctor shapes the way I think, act, plan, behave.

So lately, I’ve been conducting a kind of a social experiment to see what it’s like to be “normal.” I don’t offer up my profession to people I’m meeting. If asked in passing, I’ll say I work in health care, a pretty vague answer that still is laden with meaning in the COVID-19 era, for better or worse. I go to my gym amid the sea of heavily tattooed patrons and say absolutely nothing when I hear talk of the healing powers of crystals and essential oils. I muddle my way through conversation about heavy machinery with a tow-truck driver and learn about the different braking mechanisms of a tow truck. I keep my home largely devoid of medically related decor in favor of souvenirs and far too many plants. I feel like I’m a spy on a secret mission, my true identity unknown to those around me.

Here’s what I’ve learned from my foray into extremely low stakes espionage. There are all kinds of interesting people and perspectives outside of medicine: people who are content or searching for more, happier or sadder, wildly successful or grinding away. They are motivated by love of family, fear of mistakes, hedony, altruism, the sting of a broken heart. Taking a walk on the wild side of being a “9-to-5-er” is, in some ways, thrilling. The evenings are your oyster, free to fill with pottery class, fitness journeys, dog training.

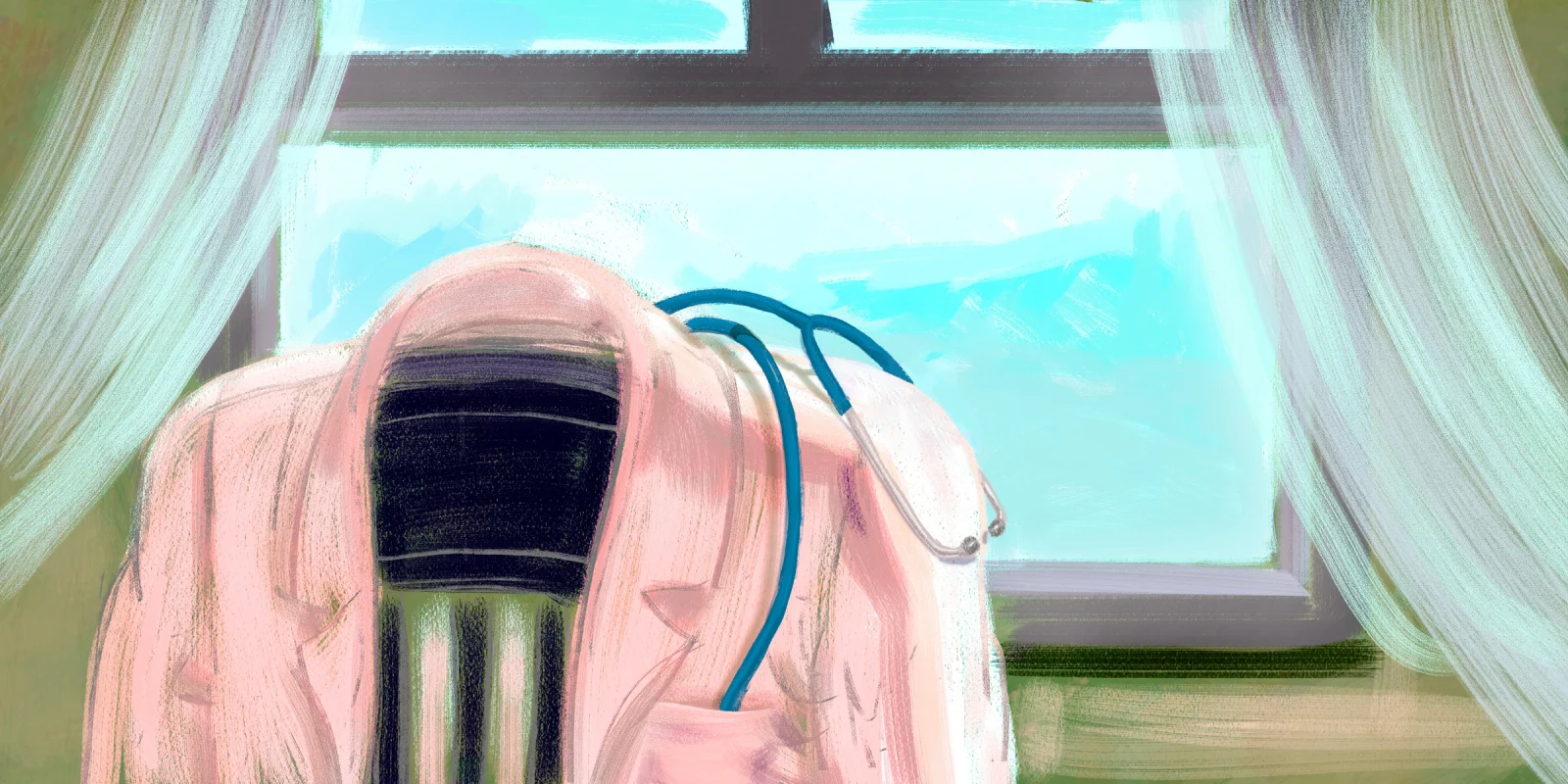

But at least for me, that life can sometimes lack a defined purpose. The practice of medicine provides that focus. Having some time in the world of normal has made me even more appreciative of the amazingly abnormal nature of my role as a physician. Spending time with my friends in medicine is a time to indulge in the insider view we are all privy to, and operating on patients a chance to slip into the zen of tissue planes. The double-edged sword is sharp on both sides though; career disappointments after years of devotion, or poor outcomes in patients for whom you’ve tried everything, deal a crushing blow that is difficult to translate. I have a lot to learn, about being a doctor and being a person and how to reconcile those two identities. A white coat is neither a superhero’s cape nor battle armor or royal regalia. It’s just a coat and I’m just a person wearing it. Hopefully, all the future retirees I come across on boats can see that.

What impact has your identity as a physician had on your personal life? Share your experiences in the comment section.

Heather is a chief otolaryngology – head & neck surgery resident at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Her clinical interests include patient communication, medical education, and facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Heather is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz