It was a Thursday afternoon when I received the call that P was being discharged from the hospital. He was a patient at our clinic who had been hospitalized for five days after presenting with severe hypoxia from COVID-19. The discharging provider on the call informed us that she stopped all the patient's oral diabetes medications due to liver enzyme elevations, instructing us to draw repeat labs and see him for urgent follow-up care.

I was a mere third-year medical student, co-leading a student-run free clinic that had long been shut down at the caution of our school administration. We were now encountering an insurmountable battle that no level of medical education could prepare us for — designing a telemedicine intervention for our community of uninsured patients who were medically, socially, and psychologically devastated by the pandemic.

As a co-chair of a student-run free clinic, I worked with other students to serve an exclusively uninsured patient population. Working closely under the guidance of skilled attending health care providers, we offered free comprehensive social work, physical therapy, nursing, pharmacy, psychiatric, and medical care for a community that likely would not have received these services otherwise. As students, we were suddenly tasked with coordinating care for patients facing unprecedented levels of unemployment, coronavirus infection, mental health needs, and social insecurity.

As we coordinated follow-up care for P after discharge, we quickly found a partner site for repeat lab tests. He had poorly controlled diabetes and suffered from diabetic neuropathy following decades of elevated blood sugar levels, so he needed to restart his medications as soon as possible.

After we received the lab results, we compared P’s liver enzyme trends to those in his prior visits. We found his liver enzymes were chronically elevated due to alcoholic liver disease. P suffered from decades of alcohol addiction and severe depression, and COVID-19 only worsened his psychiatric needs. He followed up regularly for psychiatry services at our clinic, where he had previously received supportive psychotherapy. When COVID-19 shut down all our in-person mental health services, we worked closely with our colleagues to start up regular telepsychotherapy to get patients the care that they needed during an emotionally tumultuous time.

Beyond COVID-19, many patients like P continue to go without medical care for other chronic illnesses, especially diabetes. Another patient went a whole month without insulin after he ran out because he could not afford the cost of a single refill, which was priced at $200 to $300 per vial. Insulin is by far the biggest cost for our clinic, coming out to over $40,000 a year in pharmacy costs. Our patients can get their medications free of charge because of our clinic’s charitable donations and fundraising efforts. However, it is abominable that the average cost of this life-saving medication can exceed thousands of dollars per patient per year. This has led to the deadly practice of insulin rationing in many of our patients. Affordable insulin is the key to preventing lethal diabetic complications and hospital admissions for hyperglycemic episodes that commonly occur with poor diabetes control.

Preventive services, which are often the key to reducing health care costs and promoting health for marginalized patients, are largely inaccessible without insurance. Insurance in the U.S. is tied to employment, meaning that people who lose their jobs in the COVID-19 era can quickly find themselves without coverage.

P lost his job during the pandemic, complicating the many other medical, psychiatric, and social issues that he was facing. Many of our more fortunate clinic patients continued working throughout the pandemic out of necessity — in restaurants, grocery stores, delivery services, and other essential jobs that afforded the rest of society the privilege of quarantining. These patients put themselves at risk of coronavirus infection every day to keep our country running. Their low-wage positions, in addition to placing them at high risk for infection, did not offer the necessary health insurance benefits for clinical care.

Apart from issues with medical access, we saw how our patients who lost their jobs were some of the first to suffer the effects of food insecurity and exploitative housing markets. P’s unemployment made it difficult for him to pay rent and afford food and other necessities to get through quarantine. Most patients expressed social insecurity. Others were scared to lose their apartment due to the exploitative practices of the New York City housing market. Many had to share rooms with multiple family members, plagued by astronomical rent prices from gentrification. Thankfully, we were able to coordinate a social work telemedicine outreach program and refer our patients to social services, like food hubs and rent-relief programs.

As health care providers, we made a promise to speak up against these injustices. On our first day of medical school, donned in a crisp white coat, we recited the Hippocratic Oath to “enter to help the sick … abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, especially from abusing the bodies of man or woman, bond or free." At the time, we were blinded by our naivety to see the profit-driven health care system that would force us to break this oath every single day.

In order to live up to our promise as clinicians, we need to extend essential primary and preventive care to all patients, regardless of insurance status. We need to provide access to essential medicines like insulin to every human being and better manage chronic conditions, instead of waiting until it's too late. Expanding access to preventive care can ultimately reduce health care costs. Most importantly, it can save lives. Basic health care is a human right that transcends a passport or insurance card.

As physicians, we have an obligation to care for all our patients. Many of these patients are helping us through COVID-19, so it's time that we help them, too.

Lillian Zerihun is a fourth-year medical student at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, and co-chair of the free, student-run Columbia Student Medical Outreach clinic.

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.

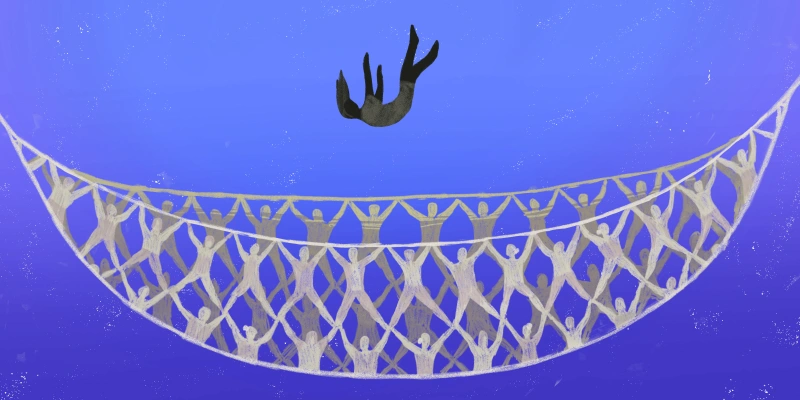

Illustration by April Brust