Teaching within the ED often feels as spontaneous and inspired as the patients themselves. The roomed patients’ chief concerns populate the triage list and an attending will pull up their “Interesting Patients” tab to discuss the can’t-miss diagnoses associated with the presenting symptoms just prior to a trainee’s initial examination. As a medical student, I received one of these classic teaching sessions when a 50-year-old woman with bloating appeared on the ED track board late Sunday night. My attending glanced over at my screen, and hurriedly pulled up a radiology report.

“I’ll never forget this one case I saw during my training. The ovarian mass was missed the first time on ultrasound in the ED. The patient came back three months later with the same unrelenting symptoms of bloating and increased abdominal girth, and was diagnosed with a high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.”

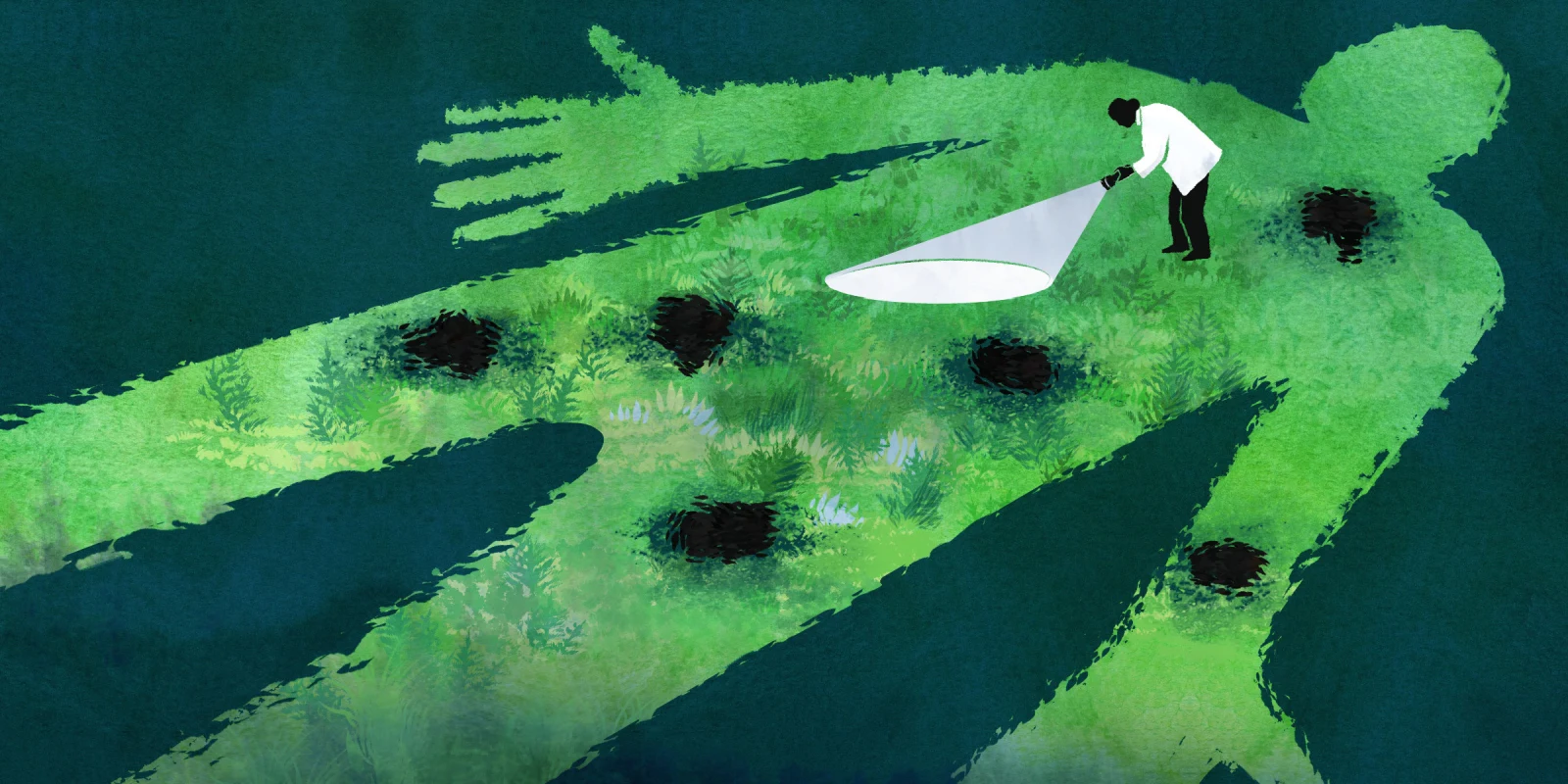

Undoubtedly, such horror stories span across all medical disciplines and levels of training. These stories are oftentimes mentioned during the pathophysiology lectures for medical students in the hopes that a future generation of physicians will prevent a similar miss, and a direct experience with such an error may be the motivation behind an attending triple-checking their fellow’s work. And, there’s good reason for this. Diagnostic errors compose the largest fraction of U.S. medical malpractice claims, cause the most severe patient harm, and result in the highest total of penalty payouts. At the level of the clinical encounter, experiencing a diagnostic error may perpetuate mistrust toward the medical system and frankly, may alter a patient’s entire life course.

The alarming nature of diagnostic errors is complicated by the concepts of disease evolution and defensive medicine. The natural evolution of a disease may be easily misinterpreted by a patient as diagnostic error if not explained clearly. Moreover, although defensive medicine may indeed prevent diagnostic error, its practice may result in serious harm. Navigating this complex interplay truly challenges the clinician at hand, and being able to work through all three with a patient is oftentimes the mark of what separates a good physician from a great one. In fact, this is what we are taught at the forefront of our medical training: the most important mitigator of malpractice is strong patient-physician communication.

During a busy winter morning in the urgent care sector of our ED, the track board triaged patients with rhinorrhea, medication refill requests, and bruised limbs after sledding accidents. As I scanned the list to identify my next patient, my eyes landed on the boomerang symbol, indicating that my next patient was re-presenting for care within 72 hours. I walked into Room 50, where three rambunctious toddlers swarmed a tired mother. I recounted my understanding of the child's previous visit, learned more about his disease course since being discharged home, and performed a quick physical examination, identifying the source of his current symptoms immediately.

“I’m really frustrated. This is the second time we’ve been here this week, the first time for a bacterial pharyngitis, and now you’re telling me he has a peritonsillar abscess? Why didn’t we catch this the first time?”

I had become intimately familiar with the concept of disease evolution during my first year of pediatrics residency. In the ED, I sat by the bedside of many parents who expressed similar sentiments. Albeit rare, one of the sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis may include a peritonsillar abscess. While the pathophysiology of this may be rattled off by even an inexperienced trainee, at the level of a patient with limited medical knowledge, such sequelae may appear to be a diagnostic error. It is the responsibility of the physician to walk through potential disease courses and provide appropriate return-to-care precautions. While I discussed the suspected evolution of this patient’s streptococcal pharyngitis and applauded her for bringing her son back to the ED, I understood her frustration and recognized our shortcomings in preparing her for this sequelae.

On a late March afternoon, I went to meet a new patient, a 12-year-old boy with anxiety who had been transferred from an outside hospital due to epigastric abdominal pain and reflux. He had been experiencing the symptoms for three days and had been prescribed a trial four-week course of omeprazole by his primary gastroenterologist, and was presenting for pain management and potential work-up. Although initial labs demonstrated a negative fecal calprotectin and a normal albumin, his parents were very concerned that the patient might have IBD and requested both a GI consult and a colonoscopy. As I watched our pediatric gastroenterologists navigate this conversation, I was struck by one of the questions they posed to his parents: “There are always more imaging and procedures that we can do, but we need to ask ourselves: Is this testing treating the patient, or is it just treating us?”

Diagnostic errors must also be balanced with alleviating the practice of defensive medicine, which is composed of unnecessary testing ordered to protect physicians from the possibility of a lawsuit for missing a diagnosis. While diagnostic errors may be prevented through this process, one must not neglect to consider the harm incurred with additional medical testing. I have found that this is especially relevant in pediatrics, when one must consider the impact of each blood draw in a neonate or the effects of radiation in a toddler. Taking the time to walk families through our decision-making and thought processes really builds significant trust, as I witnessed with our consultants and this worried family.

Unfortunately, sometimes diagnostic errors cannot be explained away as a patient’s misunderstanding of disease evolution or a clinician’s attempt to decrease the number of invasive tests. Despite our best efforts, sometimes, we just make mistakes. These mistakes may occur for a multitude of reasons, including imperfect medical technology or human oversight fueled by the many demands of our health care system. Regardless of the cause, these errors are the most difficult to talk to our patients about. These conversations are painful, humbling, and serve as reminders that our actions affect lives — not just of our patients', but our own as well.

The attending clicked out of the patient’s chart and turned to me. “So, when you see this 50-year-old, if there’s any concern that she has some sort of malignancy, we’re going to get an ultrasound. And I’ll go through the ultrasound too, to make sure that we don’t miss anything. I don’t want to make that mistake again.”

Share a time you have navigated the web of disease evolution, defensive medicine, and diagnostic errors.

Dr. Sahr Yazdani is a pediatric resident physician in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She enjoys reading, listening to Pakistani music, and trying out new Thai restaurants with her friends and family! Dr. Yazdani was a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow. All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust