Every plague engenders a clash of stories. This comes as no surprise to anyone who has been seriously ill; everything that hurts and changes us intimately cracks open a wellspring of narratives. We tell ourselves stories to understand what happens. We seek explanations and sometimes blame. We want to understand, but we also want to be understood. It is the most human of desires.

Every plague engenders a clash of stories. This comes as no surprise to anyone who has been seriously ill; everything that hurts and changes us intimately cracks open a wellspring of narratives. We tell ourselves stories to understand what happens. We seek explanations and sometimes blame. We want to understand, but we also want to be understood. It is the most human of desires.

When I was 7 years old, I had pneumonia. I don’t remember being sick, but I do remember my mother’s frustration with getting me diagnosed, which took weeks. My mother’s story went like this: “Nothing slows this kid down — ever — and she is never sick. She can’t stop coughing, and she doesn’t want to talk.” The nurses’ and doctors’ version was that I had a bad cold and a lingering, but harmless, cough. The competing explanations ended with a chest X-ray that settled the matter — antibiotics and a long recovery out of school. But when the whole world is sick, no one has all the answers.

In his “Journal of the Plague Year,” Daniel Defoe writes of the almost indescribable terror of London in 1665, when nearly a quarter of the population sickened and died in misery. Lifting their eyes from streets literally strewn with death, ordinary citizens searched the sky for signs. They saw comets - flaming swords in the hands of angels. They blamed sailors, Italy, Cyprus, the Levant, sin, misalignment of the stars, and cats. Meanwhile, the bacillus Yersinia pestis traveled on, neutral, through the bite of fleas.

In the early 1980s, although infectious diseases were better understood, media reporting on AIDS seized on gay men and Haitians - as though they were somehow different from regular people. But the virus didn’t care where it went, popping up in the blood supply, in lifesaving medications for hemophilia, in newborn babies. As a nursing student, I hovered by the bed of my favorite patient, a man whose nose had been eaten away by AIDS-related lymphoma. A bandage that didn't match his face covered the hole; it fluttered as he breathed, sleeping. His friends had brought stacks of books, all vampire stories. He was dreaming, I imagined, of new blood.

Microbes don’t have stories, or if they do, they are all the same: We will survive; we will do whatever it takes. Viruses replicate and invade, bacteria multiply; but the stories we tell are about us, not about them. The coronavirus has no nationality, no loyalty. It is neither racist nor patriotic. It doesn’t care about the economy, or haircuts, or illegal immigration or whether your child learns to read this year or how much you love your fragile grandmother. It doesn’t understand mercy or the politics of the World Health Organization. The virus isn’t because of China. It’s not even a living thing, a proper enemy. Yet it is killing us - not all of us, and some more than others. Black and brown people, old people, the poor, the servers and carers and cleaners, and yes, doctors and nurses, especially, are dying. The shocking, asymmetrical, unfair death toll is part of the human story, and if we are lucky, it’s not the end, but the middle. The virus is neutral. The enemy is our inability to reckon with it humanely: to look at ourselves and do better.

Recently, medRxiv published research showing a relative risk of death from COVID-19 of 3.5 in black Americans, and 2 in Latinos. While this research has not been peer-reviewed yet and is based on limited data — since most states don’t collect racial data on the virus — it fits with our current understanding of health inequities. We have heard this story before. We know that life expectancy varies wildly by nation, by occupation and income, by skin color, even by zip code. We also know that these social determinants of health play a bigger role than anything a provider can say in a 30-minute visit. We want to say it isn't up to us. We’re fighting a pandemic, keeping people alive; we’re trying to survive ourselves — of course we are! But we are the ones who see the outcomes. We are down in the streets with the dead and dying, but the eyes of the world are on us. We can sink in our despair, or we can wave the flaming sword across the sky.

Jennifer Hanlon Wilde, NP is a nurse practitioner, writer, teacher and student in rural Oregon.

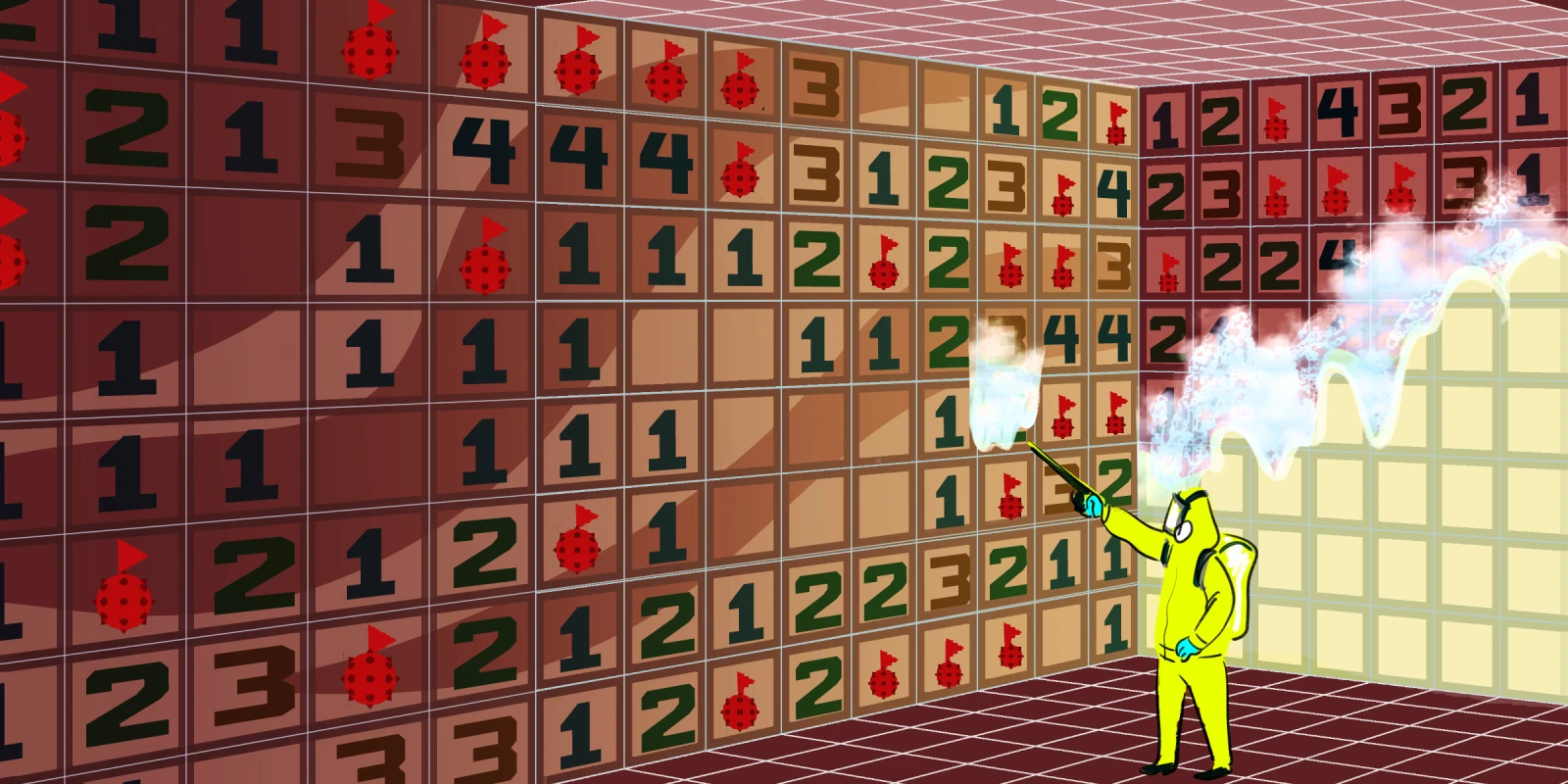

Illustration by April Brust

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.