“A chance to create a logo for our new STEM program — kindergarten through eighth grade; all submissions welcome!” That was the email from the principal that I saw one night as I caught up on school announcements. The description beckoned to me.

The next morning at breakfast I share the news about the contest with my six-year-old. “I heard about the school logo contest — you love computers and technology! You can design a logo for the new STEM program!”

“What’s STEM, Mama?” he asks. I explain each word of the acronym. “Um, OK, Mama, I’ll do it.” My son smiles.

“Let’s talk about what you want to put in your logo tonight.” My face mirrors his own, though with amplified emotion. My son has expressed interest and wants to participate — OK, it’s contained interest, but hey, it’s still interest! I feel a surge of pride about my parenting skills: Here I am, succeeding in teaching my son about the importance of finding a passion and sticking with it to completion. Nevertheless, that day, I think about my interaction with my son. Ambivalence, and the path to resolve, has always fascinated me.

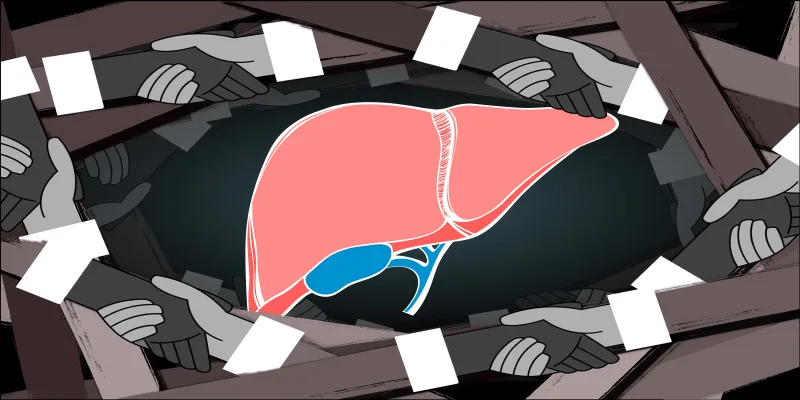

I was in residency when I first learned about motivational interviewing, an approach to patient care that involves gauging an individual’s stage of change about their substance use; listening, asking, and reflecting selectively and empathically; and resolving ambivalence to facilitate self-directed choice. It was an empowering and humbling lesson for me. The idea of reaffirming a patient’s strengths and clarifying conviction by asking, rather than telling, greatly appealed to me.

Motivational interviewing gave me hope for the moral distress I would experience about the conflicts that I observed in clinical care between the ethical principles of autonomy and beneficence. I could help my patients, on their terms, and reinforce compassion and collaboration. I sought to expand my use of motivational interviewing outside of caring for my patients with substance use disorders, applying it in working with patients with psychiatric disorders and chronic medical conditions such as diabetes or IBD. Outside of clinical care, in my work on identifying system-based solutions to address burnout, asking, rather than telling, has been central to my approach. Did I need to apply those skills to parenting? Hmmm. For now, I hang onto the thought without acting on it.

That night at home, my son and I discuss his design ideas. He wants to draw a computer and write the name of his school on the screen of the computer. He is also considering adding some illustrations of what STEM means to him: LEGO police car, an equation, a beaker with bubbles above it. “This submission is definitely a winner!” I think to myself. But the next morning, I see a tattered rendition of the design on the floor of my son’s playroom.

“Waffles bit a piece of it,” he tells me sheepishly, casting blame on our golden retriever. I glance at her. Waffles certainly looks guilty, but somehow I sense she’s not the one who is accountable. “It’s fine, we’ve still got 10 days to go on the deadline,” I comfort myself.

I remind my son about the contest a few days later. He is playing with his LEGOs and points to version 2.0. I pick it up. “I don’t understand, what happened to your idea? This is just a police car, and there’s water on this paper.”

“Yeah, that’s not my fault. Some water got spilled on it.”

Over the next week, the cycle continues. I nudge, my son mobilizes. But versions 3.0–5.0 don’t improve much more. It prompts me to reflect on my son’s behavior, but also my own, and ponder the parallels to how I practice medicine. I consider that while I have called myself a disciple of motivational interviewing for many years now, after more than a decade in clinical practice after residency, the old impulse to advise, instruct, and push does intermittently rear its head. In better moments, I have honed my self-awareness about the presence of that impulse and ability to overcome it. In other moments, I have been fortunate to receive feedback. I realize that in the reality of clinical practice in our existing health care system, one’s locus of control for helping patients can easily move to being situated squarely outside oneself, triggering all the behaviors that only achieve the illusion of restoring that locus internally. I toggle back to my conundrum at home. With each year that I field fresh parenting territory, I find myself facing the same internal struggle: How do I accept what I cannot control?

The final submission date for the logo contest arrives. That morning, my son shakes me awake. “Mama, Mama, come look, come look!” It is the kick-off to the morning scramble before a busy clinic day, but his excitement stirs my own anticipation. I follow him to his room. On the floor is the abandoned logo contest submission in no shape to be submitted.

“I don’t understand, what are you showing me?” I’m quizzical.

“Look! Look!” my son points. I follow his gaze. It is his LEGO excavator: nearly 3,000 pieces, all meticulously assembled to perfection, after three months of labor.

“I’m so proud of you!” The tears in my eyes are pride. An abandoned logo contest, now eclipsed by a LEGO triumph. His glory, not mine. But I want closure on the past week of what was clearly his ambivalence. It has been a long time coming, but I finally put the basics of motivational interviewing to use: “Can you say more about what happened with the logo contest?”

“I guess it wasn’t what I really wanted to do.” My son’s tone indicates that he regrets disappointing me. But I am the one who is remorseful, recognizing that when you seek to help someone, you must separate what you want for the person in front of you from what they want for themselves. In this way, medicine and parenting are similar: The best of your intentions are tested by the realization that choice achieves far greater impact than instruction. And with this insight, I am once again humbled, this time by my son, who reminds me of the power of asking and listening, rather than telling.

Ashwini Nadkarni, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Interim Vice Chair of Faculty Affairs in the Department of Psychiatry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Her professional passions are caring for patients and improving quality of care by addressing health care worker burnout and health care equity. You can connect with her at https://www.linkedin.com/in/ashnadkarni/.

Image by Jorm Sangsorn / Getty Images