Cardiology has historically been a male-dominated medical specialty, despite some recent improvements in representation of women. In 2020, 15% of cardiologists and only 4% of interventional cardiologists were women. This limits the amount of women cardiologists who rise to leadership positions. Consequently, only 10% of clinical trial leaders in cardiology are women.

Gender equity not only is important to improve the morale of women in cardiology and close the gender pay gap, but also contributes to better patient outcomes. A higher proportion of female general cardiologists improved readmission rates for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery bypass surgery, according to a 2022 study published in JACC.

“It can often feel like there’s not too many seats at the leadership table for women. It’s a proverbial boys' club. It is changing but pretty slowly,” said Rosy Thachil, MD, a cardiologist in New York City. “We know that there are many disparities in professional development. Women physicians are less likely to be promoted, paid equitably, less likely to hold leadership positions, and less likely to be part of an editorial board. These setbacks in professional development can accumulate throughout a career.”

Research from the American Heart Association (AHA) reinforces Dr. Thachil’s observations on setbacks. Gender diversity drops significantly at key points in the training process — starting at cardiology fellowship, falling further at subspecialty fellowship, and falling again at appointment of leadership positions. Cardiology has historically been seen as an unfriendly specialty for women, with many citing gender-based discrimination, inflexible working hours, poor work-life balance, and a lack of female role models.

All of these factors contribute to a lack of women in cardiology leadership for junior women cardiologists to look up to or be mentored by. “It can be challenging when you don’t see someone in leadership that looks like you, and it’s hard to find yourself in that position,” Dr. Thachil said. “Impostor syndrome is very real early in your career.” Improving gender diversity in leadership has not only been useful in improving morale, but also has been shown to boost the success of organizations.

While she advocates for an increase in mentoring, Dr. Thachil believes that early careerists should specifically look for strong sponsors: “A sponsor is someone who actively creates opportunities for you and puts your name in the ring. We know from research that women are over-mentored but under sponsored. You need to find someone that is willing to create those opportunities for you and be that sounding board.”

Mentorship may include verbal guidance and individualized feedback but sponsorship goes farther by providing letters of recommendation, sharing job opportunities, and carving out space for people to thrive. Cardiologists can find sponsors at various points during clinical training, including conferences, internships, rotations, and at medical universities. Dr. Thachil recommends the American College of Cardiology (ACC) as a great place to start networking, since it has programming for all levels. Notably, these sponsors don’t need to be women. Men can and should also engage in improving gender representation by sponsoring woman cardiologists and helping them achieve their goals.

Women who are interested in leadership positions may also face discrimination or bullying in their careers. “Cardiology has often carried a reputation of not being women-friendly,” Dr. Thachil said. “There needs to be a no-tolerance policy towards bullying at the institutional and larger professional level.”

In a survey of workplace bullying and hostility, 79% of 5,931 cardiologists reported a hostile working environment, with women and Black cardiologists being most likely to report harassment or bullying. Improving working environments through zero-tolerance policies and fostering a more positive working culture can benefit cardiologists of all genders.

The ACC and AHA have released policy statements both in 2020 and 2022 to update their code of ethics and provide guidance on creating a culture of “respect, civility, and inclusion” in the cardiology field. Local universities and medical institutions can further this work by instituting their own zero-tolerance policies and creating clear pipelines for physicians to report bullying and harassment. The ACC and AHA have tried to address this at their annual meetings by creating “safe space” lounges specifically for women to network with each other or have a space to come to if they need to report inappropriate behavior.

Dr. Thachil calls for more scholarships and mentorship programs geared toward recruiting medical students and young women to improve future leadership diversity: “At the institutional and local level we need to make sure that gender equity is our priority. Women need to be supported with regards to their career growth and [we need to] create tracks for women to get into leadership locally.” A clearly defined path could help lead young women toward leadership positions in cardiology, such as formal mentoring programs that could allow woman cardiologists to connect with leadership and generate opportunities for growth.

Some improvements have been made in recent years to advance gender diversity in cardiology through recruiting and conferences. Duke’s Cardiovascular Disease Fellowship Program increased applications by women by 31% over two years through a new recruiting approach. The program made changes to their fellowship recruitment committee, applicant screening process, interview day, and applicant-matching process to prioritize gender diversity. On the conference side, the ACC annual meeting has seen the percentage of women who present triple to 40% in recent years by prioritizing gender representation. While the percentage of women presenters outweighs the proportion of women general cardiologists in the field, visibility of women cardiologists can boost future representation.

Gender representation and equity in the field can be improved through continued efforts to recruit and uplift women in cardiology with proper policies put in place to protect them. "The good news is that there are greater numbers of women pursuing cardiovascular training than in previous years.” Dr. Thachil said. “This hopefully means a more diverse cardiologist workforce for the future. And this has positive implications for our patients, our healthcare systems, and our profession as a whole."

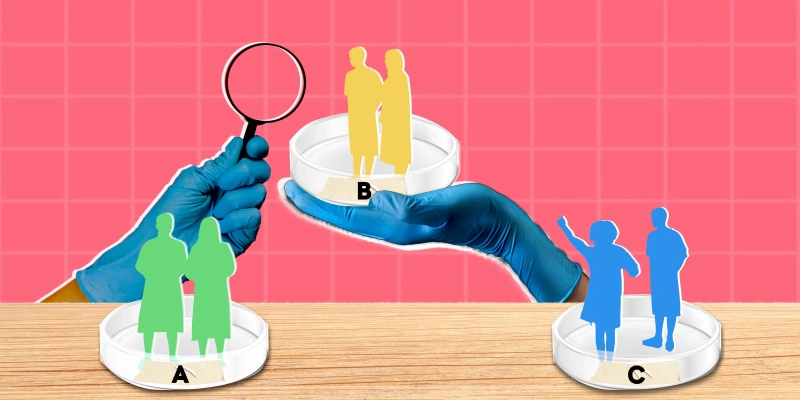

Illustration by April Brust