In a seat between a physician-podcaster and a doctor who used to be on staff at The Boston Globe, I rack my brain for a pitch. It’s week two of my medical media elective, and as we go around the room, hearing pitches for op-eds, podcasts, and short films, I think to myself: Who cares what a first-year medical student thinks?

When I said I didn’t have a pitch, the physician who taught the elective advised me to find my angle first: What did I, uniquely, have license to talk about? I realized that because I was in my first semester of medical school, I was newest to the field of medicine. I could give a unique voice to how medical experiences felt when everything was a first.

Later that semester, I went home for Thanksgiving break. There, I told my friends about the rapid pace of learning at school, the parade of professors we had, and the classmates I had met, who ranged from former NASA scientists, to parents, to Fulbright scholars. Then, I brought up the anatomy lab, and their curiosity felt insatiable.

What’s the coolest thing you’ve seen? How do you dissect a body? Do you feel like a doctor now?

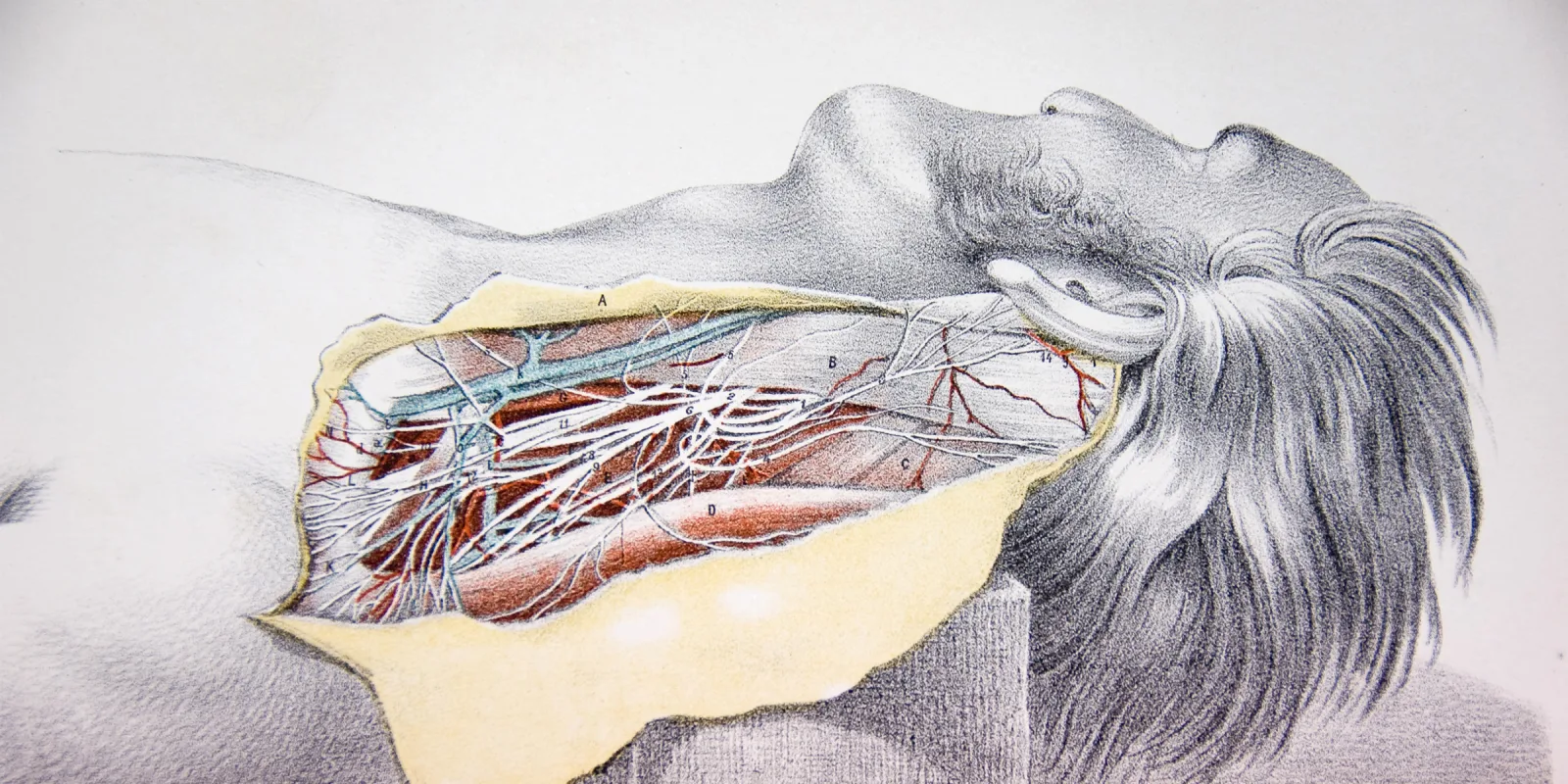

At the time, I could tell my friends that the coolest thing I had seen was a human heart, which was exactly as I had seen it in textbooks. I could say that enclosed in our dissection toolkits were scalpels, scissors, forceps, even a bone saw. But even if I had cracked ribs and held a brain, I couldn’t say that I felt any closer to being a doctor, yet my friends made it clear that my experiences already had set me apart.

Anatomy lab had become a regular part of my schedule. It was densely packed with discoveries, challenging experiences to process, and unexpected connections with my own humanity. Rightfully so, my friends had many questions about it. They helped me realize that, as someone so curious and sensitive to everything new about the experience, I could be a bridge, in my storytelling, between folks not in medicine and clinicians with long careers.

Sometimes, a professor or seasoned expert in anatomy may not be in tune with what students — most of whom have never seen a cadaver — feel. Before our first lab, each group was connected with a pair of students in the class above us, and those second-year students were our bridge to the experience instead. One older student had told my lab group that anatomy was what made her “feel like she was in medical school.” Another reminded us to treat the donor’s body with respect and dignity: no unnecessary uncovering of the body, no gallows humor, no pictures. They reminded me that at the end of the day, this was a human-to-human experience between a donor and a group of students.

I told my friends that I had seen the donor’s face and hands. From the first day, my dissection group wanted to recognize the person’s humanity, so we unwrapped the parts that felt most human to us until there, on the dissection table, was the body of a person we would never fully meet.

A month after that initial encounter, I would see a strikingly similar face, walking out of a cafe, with a coffee in their hand. I felt I had seen a ghost. Unnerved, I thought about emailing my professor, explaining that I didn’t feel I was in the right state of mind to go to the anatomy lab the next day. But I would soon realize that maybe this experience was a reminder that donors, too, walked this earth, and held coffee, and met the awkward stares of tired medical students. In just a few weeks, I had lost touch with the humanity of the donor. So the next day, I returned to the lab with a bit more gratitude, given that a complete stranger donated their body so that they would be able to teach medical students. It was as if they believed in me more than I believed in myself.

It was interesting to participate in an experience that felt like part of a long initiation process in becoming a doctor. Some future doctors will never use a scalpel again or peer into the viscera of the human body outside of medical school, yet anatomy lab is still required at most institutions. For doctors, it’s a nearly universal experience, but each person engages with dissection differently. For one of my peers, the demographics of the donor kept reminding her of a loved one she had lost. For another, the emotional distress of cutting into someone who had passed made it difficult to focus fully on the dissection. Although their experiences were theirs alone, I felt a strange kinship with them when I heard their honesty: I felt comforted that they, too, had struggled.

First-time experiences, like cutting into the human body, become touchstones to engage with later. Maybe it was the awe inspired by watching a patient improve after a risky surgery, or the adrenaline of responding to a code, or the excitement of unraveling a patient’s puzzling history that drove us toward our careers. Memories of firsts are like photos we keep in our wallets. Every now and then, we pull them out to remind ourselves of why we started to pursue medicine in the first place, and reflect on how far we’ve come from our first days of medical school.

As I collected these experiences, I was intent on reflecting on the emotions they provoked, and I felt that trainees were especially close to those emotions and their novelty. So I kept sharing stories to shed light on this human side of medical training that would be relatable to a broad audience. I spoke with students who grieved the first loss of a patient; my mother, who delivered her first child as a pathology resident in NYC; and a family medicine doctor, who, with her heart pounding, responded to her first emergency on an airplane. I wrote so often about future doctors because I felt that the novelty of their experience of medicine felt so attentive to emotion, and so intimately human.

A bridge between medicine and the public, students have a fascinating, humanizing perspective on medicine. Their stories are worth telling.

Amador (“Tino”) Delamerced is a medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. He is the producer of Firsts, a podcast series about first-time experiences during medical training. Tino is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Image by mstroz / GettyImages