As a resident, though you are learning about everything, you inevitably create mental lists of your favorite and least favorite pathologies to treat. Neurosurgery residency gives us ample opportunity to work on differentiating ourselves toward tumor, spine, vascular, functional, pediatrics etc. But, whether we like it or not, our program in St. Louis prepares everyone well for how to manage neurosurgical trauma patients. When looking back on my experiences thus far, multiple sources of trauma stand out: car crashes, ATV accidents, and, perhaps — depressingly — most representative of the St. Louis area, gunshot wounds (GSWs).

It is the latter that has really impacted my time in residency. The sheer volume of daily MVAs still is surprising to me, though many drivers in St. Louis are known for having loose regard for traffic laws and stop lights. And growing up in Indiana, I knew people who rode ATVs. These vehicles have a propensity to flip, sure, but intuitively the risks make sense given their similarities to motorcycles, dirt bikes, jet skis, or similar things. Residency has shown me that while people should definitely be more careful when riding these — and please, please wear a helmet — they less commonly have the capacity to decimate families or entire communities.

GSWs, on the other hand, I was not personally familiar with. I was fortunate enough to grow up removed from gun violence until I entered medical school in St. Louis. There, I learned about the epidemiology of gun violence and the social impact that guns have in the areas in which many of our patients reside. St. Louis, as multiple studies have shown, has among the highest rates of gun violence in the U.S. And while I could learn in school the impact that gun violence has on patients, the real crash-course began when I entered residency.

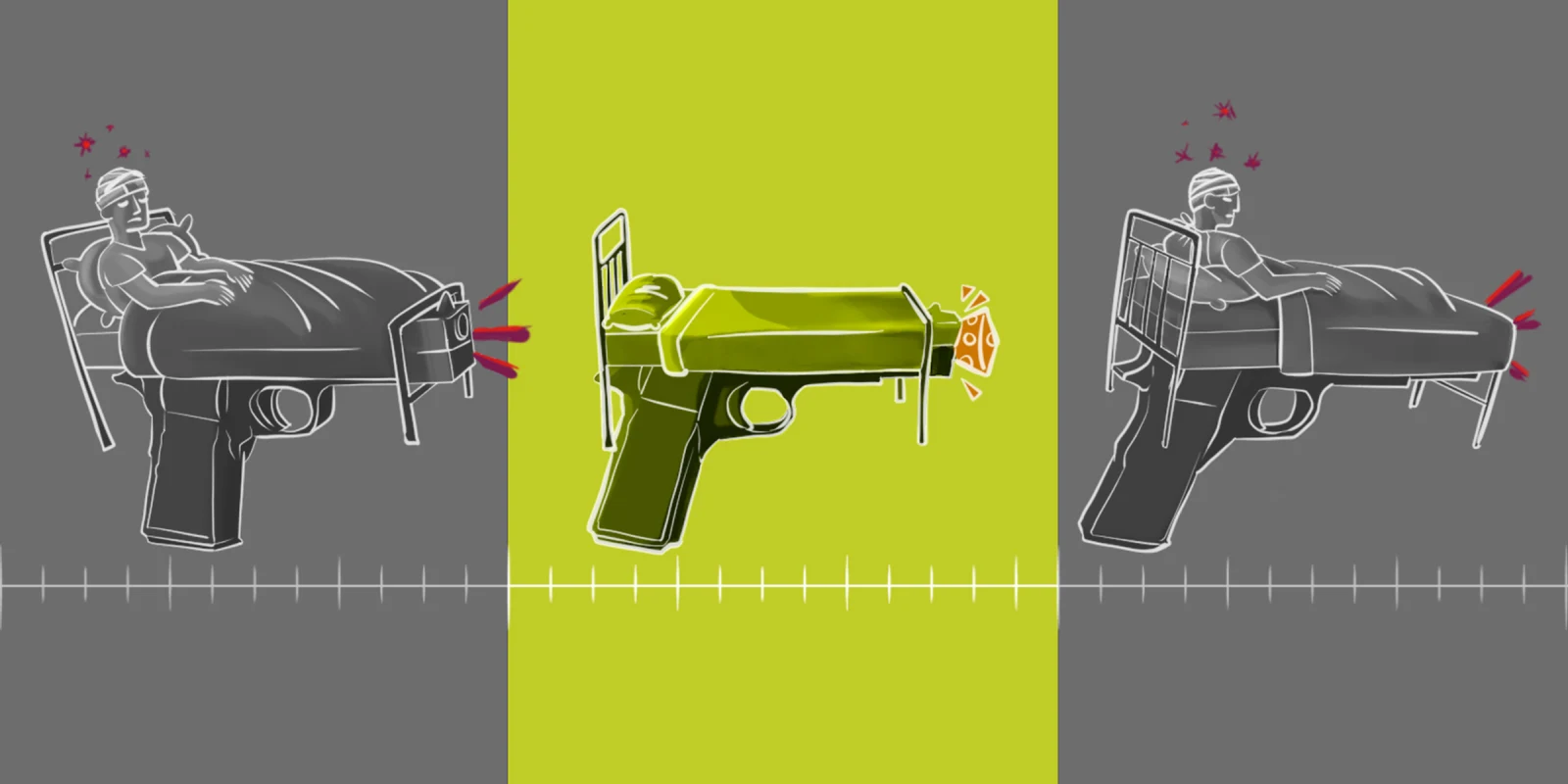

Of all the consults we see in neurosurgery, my least favorite is the GSW to the head. The simple reason is that we can so rarely make meaningful changes in these situations. The outcomes are horrific. Though we overall see fewer GSWs than does general surgery or perhaps even orthopaedic surgery, GSWs to the abdomen or extremities can be more frequently salvaged. They incur substantial morbidity to patients, but the overall mortality is better.

Neurosurgery sees the most dismal GSWs — and these are the “lucky” patients, the ones who survive long enough to make it to the hospital. After arriving at the ED to evaluate the patient, we are always asked the same thing: “Are you taking this patient to the OR?” The truth is that we don’t really know until we have a head CT. The true damage done by a GSW can be hard to determine from an exam alone. The patient could be unresponsive due to severe TBI from the concussive blast force of a bullet that mainly involves the skull. They could have unilateral damage for which a decompressive hemicraniectomy may provide some benefit. Or, they could have bilateral hemispheric damage with vascular injury, for which intervention would be futile.

In my time seeing these consults — which, granted, is one resident’s experience, though still comprising a relatively high number of patients — the most dire example is the most frequent. Such patients have catastrophic intracranial injury, poor neurological exams, and no chance to benefit from a surgical procedure. At first glance, they may be stable on a ventilator and with pressor support, but the delayed cerebral edema or expanding hemorrhage that will ultimately take their life has not fully kicked in yet. I send a video of the CT scan to my attending, discuss their history/exam, and we arrive at the same plan: supportive care until family or other decision-makers are ready to make end-of-life preparations.

Of course, as the neurosurgery team, we initiate many of these discussions. Inherent to the cranial GSW consult isn’t just the decision whether to operate. It’s also breaking the news to families, discussing prognoses, answering questions, and determining next steps. Sometimes, we help clean the patient up before family sees them. Some of the most vivid memories of my junior residency involve using DuraPrep sticks to wipe away brain that was actively herniating out of the scalp so that I could quickly place stitches through bullet entry/exit sites and save the family from an even more gruesome scene of their loved one who was not a candidate for surgery.

In addition to GSWs to the head, we also are consulted for GSWs to the spine. These, in more fortunate cases, may only cause fractures that require bracing or short-segment surgical stabilization. In sadder instances, the bullets cause irreversible damage to the spinal cord. These patients will have to adjust to life with paraplegia, neurogenic bladder/bowel, pressure sores, etc., but their mental capacities may well be left intact. These situations, overall, aren’t as catastrophic to families.

What’s also disheartening about the high volume of gun violence that we see in St. Louis is that it doesn’t only manifest in adults who are actively taking part in that violence. Plenty of innocent bystanders are struck by stray bullets simply as a result of the socioeconomic or other forces that placed them in high gun violence areas. We in St. Louis are moreover unfortunate enough to have a high number of pediatric GSWs, enough to spur the creation of the St. Louis Scale for pediatric gunshot wounds to the head. At the time of writing this article I have been rotating at my program’s children’s hospital for six months and have seen several GSWs to the head. None of these children were personally involved in a shootout. Only one received surgery. None survived longer than a few days after being shot.

To clarify, this is not an article purporting to offer ways to address the gun violence epidemic in America (though it would be nice if politicians had to personally see what happens in our ED during any given shift, especially in the summertime when I’ve noticed that violence picks up). It’s more my personal reflections as a resident who is training in an area so affected by guns. We see multiple GSWs a night in our ED, of which I see only a fraction. But, having spent so much time in the ED, I have passively noted the significant resources that are put toward these patients on a regular basis — the multidisciplinary trauma responses, the transfusions, the resuscitation efforts, the imaging, the emergent procedures. I have heard the wails of distraught family members, seen codes aborted, and watched patients covered by sheets in the ED, even if I wasn’t actually involved with their care. Every time, I have to reflect on how senseless — and, compared to other developed nations, how uniquely American — this violence is and how little we as residents can do to prevent it on any large scale or appreciable timeline.

Dealing with both the clinical and emotional aspects of GSWs comprises a necessary part of trauma education for many specialties. So, I suppose, it is strangely beneficial that I have had the chance to train in such a location. That said, and I’m sure every physician would agree, it would be far better if we didn’t need to undergo so many of these particular learning experiences.

What consult do you dread the most? Share in the comments.

Dr. Alex Yahanda is a PGY3 neurosurgery resident at Washington University in St. Louis. He also received his MD and MPHS degrees from Washington University. Dr. Yahanda is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust