In my third year of medical school, with the typical confidence of someone steeped in theory but lacking practical experience, I assured my supervising surgeon that our patient was fit for surgery, despite their low platelet levels. "The platelet count is above 50K," I argued, "well within the acceptable range."

I was a third-year medical student in a rural, critical-access hospital in northern Maine. We were about a five-hour drive north of Portland. The hospital and its staff provided exceptional care to the community. They also referred many patients who needed specific specialty care to the larger hospitals in Portland and Boston. While I had grown up in a rural area, I had spent much of my adult life in a large urban city and had become used to its advantages, from availability of medical devices and products to access to specialized physicians.

The surgeon looked at me flatly. “What would you do if the patient bleeds on the table?”

I timidly offered: “Transfuse platelets?”

“Good luck,” the surgeon retorted. “There are no platelets within 100 miles of this hospital. Evidence-based guideless don’t mean much when there’s literal blood on your hands.”

The first time I heard the term “OSH” was the second rotation of my intern year. I had moved to Philadelphia for residency, working at a large, quaternary academic hospital system. In addition to a rapid crash course in being a doctor, I was quickly learning new terms and conventions. OSH stood for “outside hospital.” It was pronounced as a single word, osh, not the abbreviation O-S-H.

I was mildly surprised; in medical school, part of the history of present illness included a comment on the hospital or region the patient was transferred from. In Maine, the medical community was fairly small and reasonably interconnected. And where the patient came from provided helpful context. One patient from the coast may be missing lobstering season, stressing his family’s finances. Another may be hundreds of miles away from the town that he and his family had lived in for seven generations and wanting nothing more than to go home — important perspective for goals of care conversations in the setting of a new diagnosis of metastatic cancer.

And there were tangible benefits too — I have called colleagues at different hospitals across the state to help track down medical records.

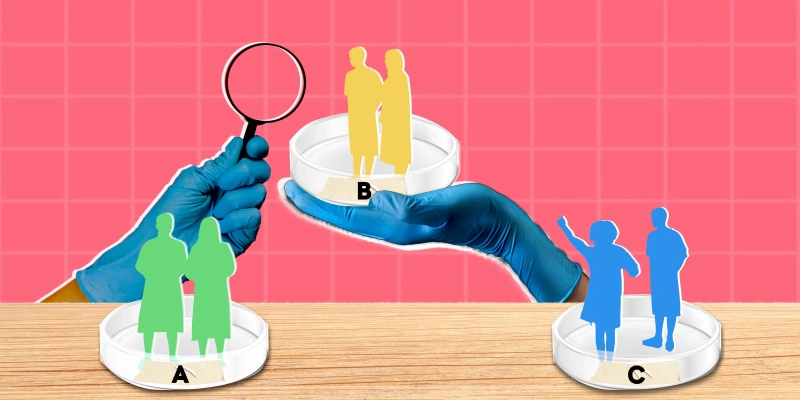

I learned quickly that OSH was not a good thing in residency. My co-residents and I would spend hours trying to piece together a story from a thick packet of notes that were not infrequently dozens of pages of daily lab results and no discharge summary. Rationale behind medical decisions was murky. Unintentionally, my co-residents and I developed a critical stance toward these external institutions. Patients were angry about how long they had waited for the transfer. Because the hospital was always so full, transfers were delayed days or even weeks due to bed availability.

Sometimes the transfers were frankly dangerous. Once I received a call from a panicking nurse about a patient who arrived from an OSH on pressors. We subsequently and expeditiously transferred them to the ICU.

Despite my very real frustrations, I felt vaguely uncomfortable with the criticism. In medical school, we had sent patients with rare, complicated diseases to the large research hospitals in Boston. Did those clinicians scoff at our management? Did they even know where the patient came from — or was it just another OSH to them? Did they know that we didn’t even have platelets available?

As I’ve matured over residency, I’ve come to appreciate the complex calculus done by health care practitioners under constraints. At times, even in my large academic medical center with many layers of backup as a trainee, I have been acutely alone and needed to make a fast decision. All I could hope was that my colleagues wouldn’t judge me too harshly the next day.

My respect and regard for my colleagues at surrounding and smaller hospitals has grown immensely. The specific scenarios and constraints we find ourselves in are uniquely experienced. It’s important to give grace to our colleagues. I try to be more intentional with my notes and words. The OSH team had cared for the patient until they decided they needed outside help. I am more than happy to help.

Share your experiences on working at rural versus urban clinics or hospitals in the comment section.

Corinne Carland is an internal medical resident at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She is interested in health tech, clinical informatics, cardiology, and genomics/proteomics. Outside of work she enjoys walking/running along the river, trying new ice cream spots, and exploring museums. Dr. Carland is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust