Tiny as a baby bird, one of my critically ill patients weighed just under 500 grams when I was a medical student on my pediatrics rotation in the NICU. He didn’t even really look like a baby, more an alien with near-translucent skin, eyes seemingly fused shut, fingers long but as thin as matches. Too underdeveloped to regulate his body temperature, he was kept in the warmth of an incubator that responded to a temperature probe on his skin. With underdeveloped lungs, and being unable to suck or swallow, he required a breathing tube and a central line for pressors and nutrition. He was just 23 weeks gestation when he was born, a delivery that was brought about precipitously by his mother suffering from trauma while in a car accident. It was in those quiet moments under the steady hum of the ventilator and the beeping of the monitors that I simultaneously marveled at the capabilities of modern medicine and wondered to myself what his life would be like in the coming months. I would later come to find that he died from a ventilator-associated pneumonia only a few weeks later, life extinguished before it even had the possibility to flourish.

The Guinness World Records reported in 2021 that the world record for the most premature baby to survive thus far is a boy named Curtis, born in July 2020 in Birmingham, Alabama after only 21 weeks and 1 day gestation. Receiving around the clock care for the next nine months in a level 4 NICU, he was discharged with home oxygen and specialized nutrition. The joy of his survival was bittersweet, as his twin sister passed away just a day after their birth. How did he survive while his sister did not?

From decades of research in neonatology, there are now factors that can inform whether an extremely premature neonate might have a higher likelihood of a better outcome (surviving without profound non-ambulant cerebral palsy or severe cognitive disability): higher gestational age, singleton birth, female gender, higher birthweight for gestational age, and exposure to antenatal steroids. Curtis never had any of those factors favoring his survival, and yet he lived. The very nature of pediatrics as a specialty, and one of the many reasons I chose this field for my career, is that kids more often than not get better when they are sick. But as modern medicine continues to push the limits of viability further toward lower gestational ages, where does one draw the proverbial line in the sand?

This was the very question I asked myself many times while in the NICU as a pediatrics resident a few months ago. In one room, a patient of mine born at 25 weeks gestation months ago was finally extubated after weeks of being on a ventilator and was now slowly learning how to eat on his own. His brain was healthy, and he had not suffered from the interventricular hemorrhage that many premature babies experience. There’s no saying with absolute surety, but he may one day live a near-typical life. Another of my patients a few doors down, a baby girl born in similar circumstances, had severe complications in nearly every organ system and continued to be intubated, NPO, and was being monitored for high-grade interventricular hemorrhage. With all of her complications, the likelihood of her needing constant medical care for the rest of her life was very high. While the first patient slowly but surely progressed, the second remained stagnant.

The second patient’s mother, in almost constant vigil by her side, was now very experienced with the roller coaster that was her daughter’s care. However, she continued to carry hope and smiled and greeted us on rounds. While every decision made for her was done with the utmost care for evidence-based practice, I continued to wonder whether we were doing more to her daughter rather than for her. In other words, where on the scales of beneficence and non-maleficence did our daily decisions for her fall? How do you give families realistic expectations for their child’s future without snatching hope away? I once asked the same mother what she thought of her daughter’s life so far. She replied simply with, “It’s full of very high highs and the lowest of lows, but it’s also full of love.” Although I could not truly put myself in her shoes, we at least connected over our shared acknowledgement of her daughter’s persistence to cling to life despite everything.

The more I reflect, the more it seems that the answer to many of my questions lies within the struggle to understand the “why.” Equally frustrating and fascinating is the fact that neonatology is still a budding field full of questions but not nearly as many definitive answers. Just as there might have been a reason Curtis’s sister did not survive while he did, there may or may not be reasons why my current patients forge such different paths even in their earliest days of life. Perhaps what would solve my cognitive dissonance would be to recognize that despite my beliefs when I chose pediatrics as my specialty, not all kids get better. Some will truly defy all odds, while others will die or suffer complications despite all efforts. As the field itself develops more definitive answers for which neonates may have better outcomes, perhaps we will have better answers for what makes all our interventions worth it for saving the youngest of lives.

Dr. Zahur Fatima Sallman is a resident physician in Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Michigan. She is a graduate of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. She loves acrylic painting, pizza making with her husband, and considers herself an amateur carpenter. Dr. Sallman is a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow. All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

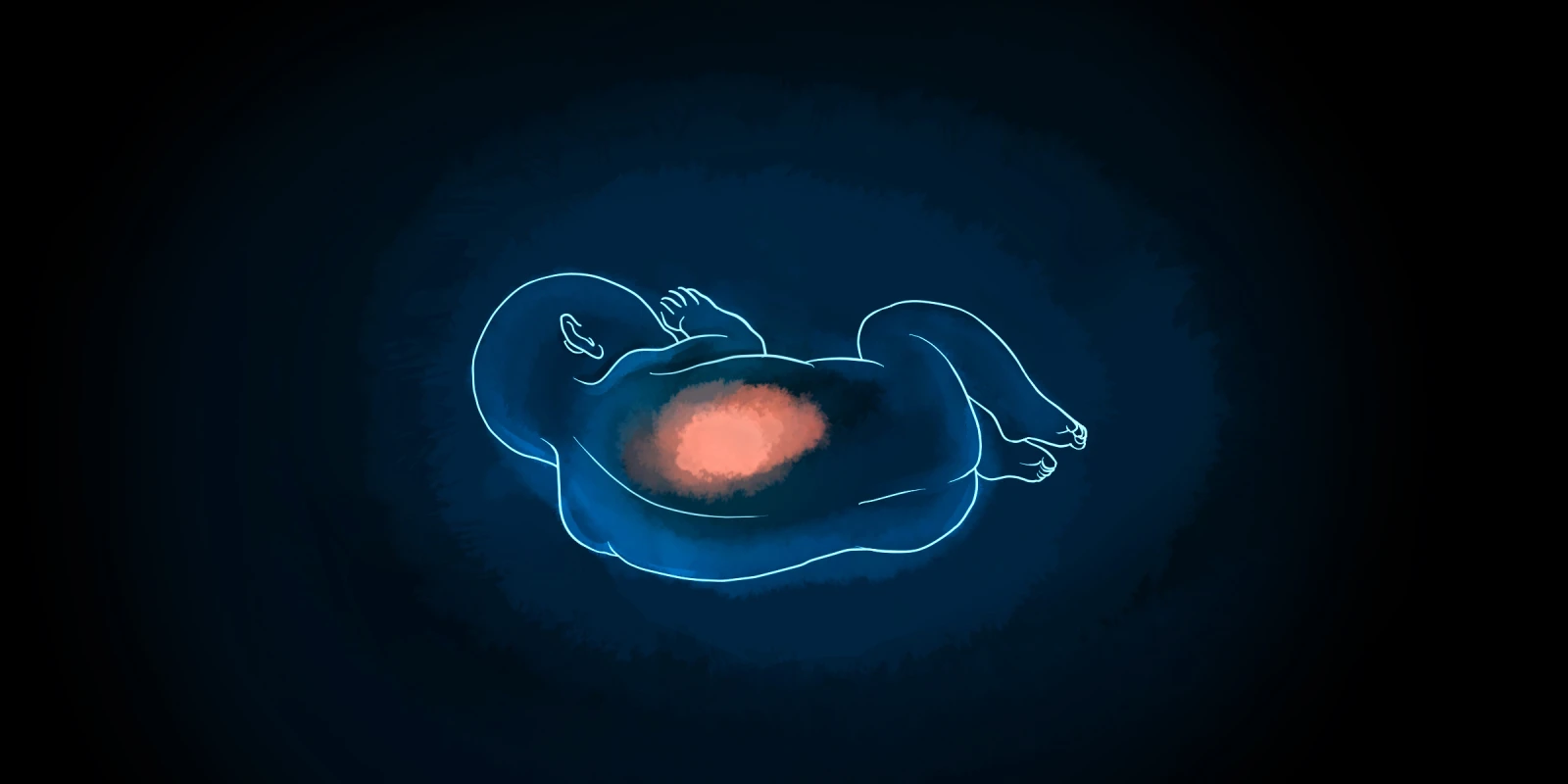

Illustration by April Brust