It is 2035, my last day of work after 30-plus years of clinical radiology. Before I leave the medical imaging fulfillment center, I unstrap the heads-up display helmet of my virtual reading room and walk down the service tunnel to the westward-facing patient loading dock to look at the sunset.

When I first started radiology residency, I worked in an enormous urban academic teaching hospital, which was constantly humming with human activity — enough foot traffic to rival Walmart. Our attendings had just celebrated the 100th anniversary of Roentgen’s discovery of the X-ray. We were taught about the Nobel Prizes related to CT and MRI, and how lucky we were to be in a field that had won and was winning the technology lottery.

My earliest rotations in residency were with the most esteemed, long-bearded, and wizardly attendings who took two to three months of our first year to teach us barium radiology, upper gastrointestinal (GI), barium enemas (BE), and the mystical arts of double contrast enteroclysis, a specialty of our teaching hospital. I grew to appreciate barium radiology because it was one of the most intimate and personal radiology exams. I was with the patient during most of the exam, talking them through a very delicate procedure, sometimes even holding their hand.

Now, years later, we don’t do BE or upper GIs anymore, and I realize that I had given up on being a barium wizard a long time ago. Barium studies have not been regarded seriously as authentic problem-solving tools since the days of my residency. Instead of a crowded university hospital, I work in a “big box” facility, in a giant mall, between the dollar store and the cannabis dispensary. I process more than twice as many radiology exams than anybody in the teaching hospital ever did, but most of these exams are performed on patients who are not in the same place and time as me. Despite the large capacity of our imaging fulfillment center, most of the exams I read are performed on patients in a different location. Likewise, most of the patients who come to this facility have their studies read elsewhere, sometimes in another country.

So I never see a patient in person. In fact, the most recent owners of the facility, the giant online shopping and media corporation, Metazon, suggested that we forgo using patient names and instead use their unique medical shopping user ID for seamless integration and easy ordering of online medications. The corporation has helped us implement a lot of efficiency upgrades, including the patient transport and preparation automaton, based on their vast corporate experience in delivery of online retail. The maze of rail-guided mobile gantries that lead directly into the bore of the CT and MRI scanners is quite impressive to watch. The patients are nestled comfortably in these high-tech patient holders, constantly entertained during their exam by Metazon video and music streaming.

The corporate owners also upgraded our IT systems, which has allowed me to supervise AI reading of even more studies. The AI improvements mean I only have to correct 70% of its reports, which according to the corporation, is still too high compared with the younger radiologists, who are trained with AI, and in my opinion, by the AI.

I do admire my younger colleagues, even though I’ve never met them in person, because of their efficiency and inherent trust of technology. However, I would not make the Faustian bargain for greater efficiency if it meant that I had to adopt the disingenuous technological corporate mindset that further blurs the distinction between health care and consumerism. The vast majority of the abnormal findings we make in the medical imaging fulfillment center are unrelated to the patients’ own experience with their health and detached from any treatment plan. This is because they are often incidental findings, or because we image the patients before anyone has obtained a patient history, or because more than half the patients we see are completely asymptomatic.

The corporate owners, like many large employers, give their workers annual vouchers for free whole-body screening exams, sometimes in lieu of medical insurance. Most workers love this, because they like getting high tech exams for free. Some of the wealthier corporations at least auto-refer abnormal findings to their national network of AI-supervised NP and PA primary care networks, who then usually order even more medical imaging, without generating a treatment plan. Unfortunately, life expectancy and health inequality in the U.S. has continued to worsen since the wave of pandemics and climatodemics that began in the 2020s.

For radiologists, it is, to use a stale cliche, “job security.” For me, I am not sure that mass generation of abnormal radiological findings in the absence of any clinical context on overworked minimum wage employees counts as health care. Perhaps I am too attached to the idea that a patient is a person who has a medical problem and a differential diagnosis, not a person who has an insurance card.

That is the philosophy that I was taught in medical school. It is hard to put this aside because for me, the proper philosophy is the difference between a calling and a job. Going even farther back to college, I was taught in sociology that doctors were like artisans. Our work grew from personal, maybe even unique expertise, and thus we had virtuous ownership of our work, like a carpenter making a table. We even had guilds (usually called the state medical board), just like feudal artisans. Nowadays, many doctors feel alienated from our ever-increasing burden. Our major concern is not our relationship to our patients, it is our relationship to our employers. We are proletarians — less skilled tradesmen and more generic employees.

As the sun sets over the patient buses in the parking lot, I am surprised by a phone call. It is John, the technologist, the only other person in the imaging fulfillment center besides me who is paid above minimum wage.

“Hey, Doc. There's an old man here at the front desk who wants someone to explain to him why his back hurts and what his lumbar spine MRI shows. I tried to get him to watch your YouTube video and I referred him to SIRI and Alexa, but he is insistent on talking to a person. You're the only old guy left who talks to patients. Would you mind?”

“OK. No problem. Please put the spare image-viewing helmet on him so that I can show him the pictures. Strap him to gantry rail line G4 to the basement. The reading room is Cubicle 42G.”

Not a bad last thing to do on my last day.

How do you envision AI changing medicine? Share your thoughts in the comment section.

Jimmy Leung is a musculoskeletal and MRI radiologist with 20-plus years of experience. He grew up in Hawaii, studied and trained for many years on the East Coast, and now works in the Southwest. Dr. Leung is a 2022-2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

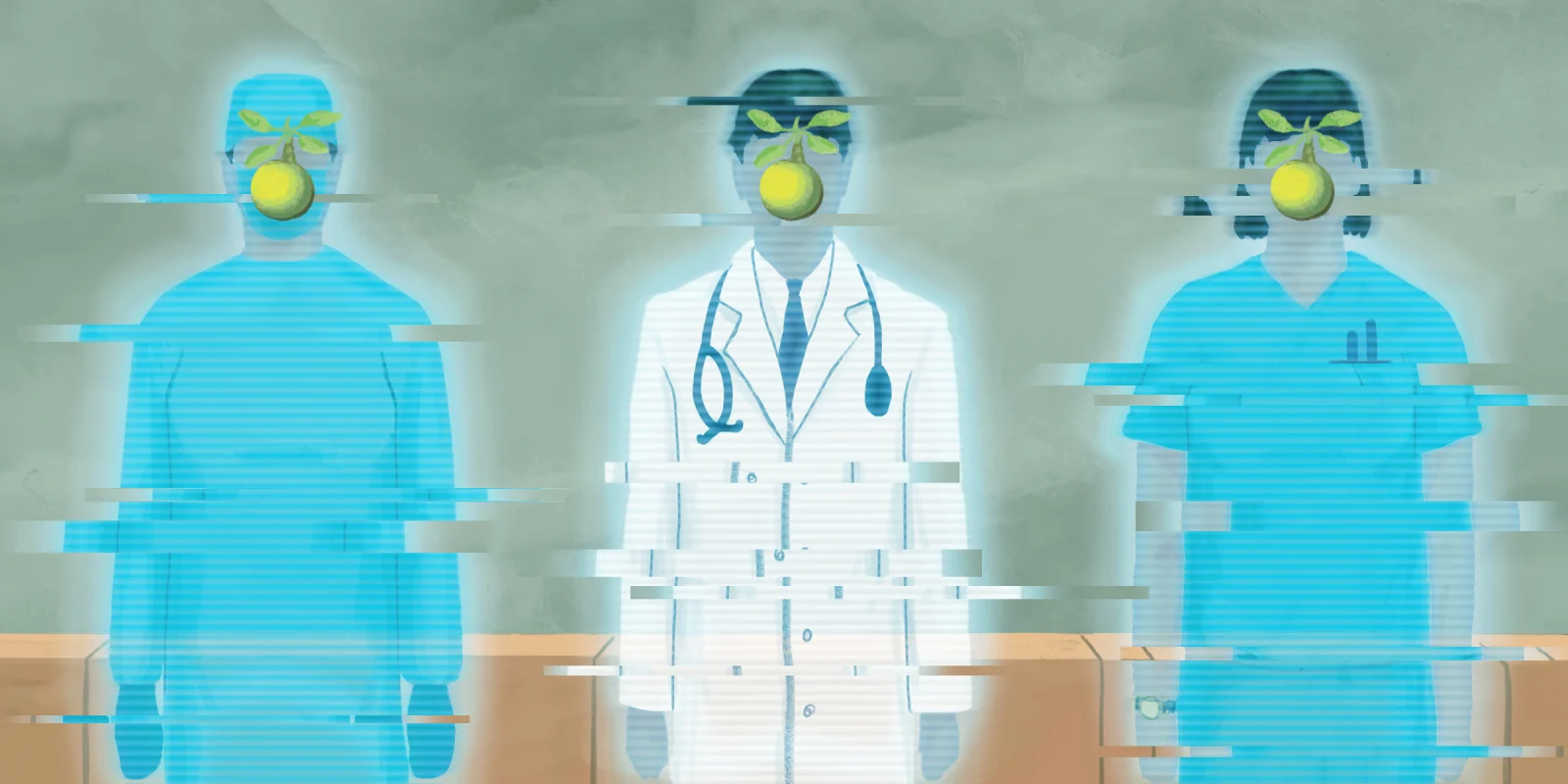

Illustration by Diana Connolly