Like many other mornings during my third year of medical school, the first day of my neurosurgery rotation started with rounds. As I scanned the list, one patient stood out to me in particular because we shared the same birthday. He was 16: diagnosis of a gunshot wound.

Like many other mornings during my third year of medical school, the first day of my neurosurgery rotation started with rounds. As I scanned the list, one patient stood out to me in particular because we shared the same birthday. He was 16: diagnosis of a gunshot wound.

During the physical exam that morning, the resident noted that this patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale was worsening and he would need another CT scan. With that order in place and rounds complete, we headed to the OR to start the first case. Before we scrubbed in, we reviewed the CT scan. There were signs of increased intracerebral pressure and urgent surgery was needed. Following the completion of the first case, the team prepared for the 16-year-old’s decompressive craniectomy.

With the patient’s head unwrapped and prepped for surgery, every detail intensified. Streams of dried blood emanated from a volcano formed of cragged bone, peaked with gnarled metal, and oozing gray matter. We drilled boreholes and with the removal of the skull flap, the remains of the bullet fell to ground; rugged exterior exchanged for primeval mush. A lake of coagulated blood and minced neurons lay surrounded by rolling hills of gyri and sulci. As the resident irrigated, washing away clots and shredded cerebrum, a dime-sized piece of brain dislodged and fell on my shoe. Overwhelmed, I focused on my breathing and helped finish the case.

Afterwards, we updated the patient’s father. What sticks out to me most from this conversation was the father’s guilt. He continued to reiterate how excited his son had been to be dropped off at a friend’s house. Ten minutes after that, the dad got a phone call that his son had shot himself. Stories differed between the people present during the shooting, but multiple reports indicated that the friends were jokingly playing Russian Roulette. I had never felt more revulsed. We entered this patient’s room two days later to find him covered with a sheet. He had died two hours previously, two months shy of his 17th birthday.

Months later, I still think about this patient and his family. What sticks with me most is our similarities. Not that we shared birthdays, but that we experienced the same emotions. Four days before he died, that 16-year-old was excited to go to his friend’s house, just as I was many times as a teenager. And long before that, I know he felt all the same emotions I experience: joy, hope, love, anger, self-doubt, fear. I am drawn to this emotional connection because it is the only human aspect of this patient I can identify.

I cannot recognize his humanity through any of the structures I saw in the OR that day because they were altered past recognition. The brain I saw was not human, all its life was gone, replaced by an inorganic primordial wasteland of volcanoes, lakes, and streams. Another reason why this case is so prominent for me is that it was the first patient of mine that died. I knew coming into medicine that I would have many patients die, but I always envisioned these patients as old with an incurable disease, not a teenager looking to impress his friends. I see now that medicine is frequently inequitable and that we healthcare providers often see patients dehumanized before we ever get a chance to connect with and help them. Coming into medical school, I knew it would be a privilege to care for patients. I did not initially appreciate the horrors and injustice that accompany medicine, but then someone’s brain fell on my shoe.

Evan is a fourth year medical student at Indiana University planning on matching in Internal Medicine. In his free time he enjoys hiking, cycling, and skiing.

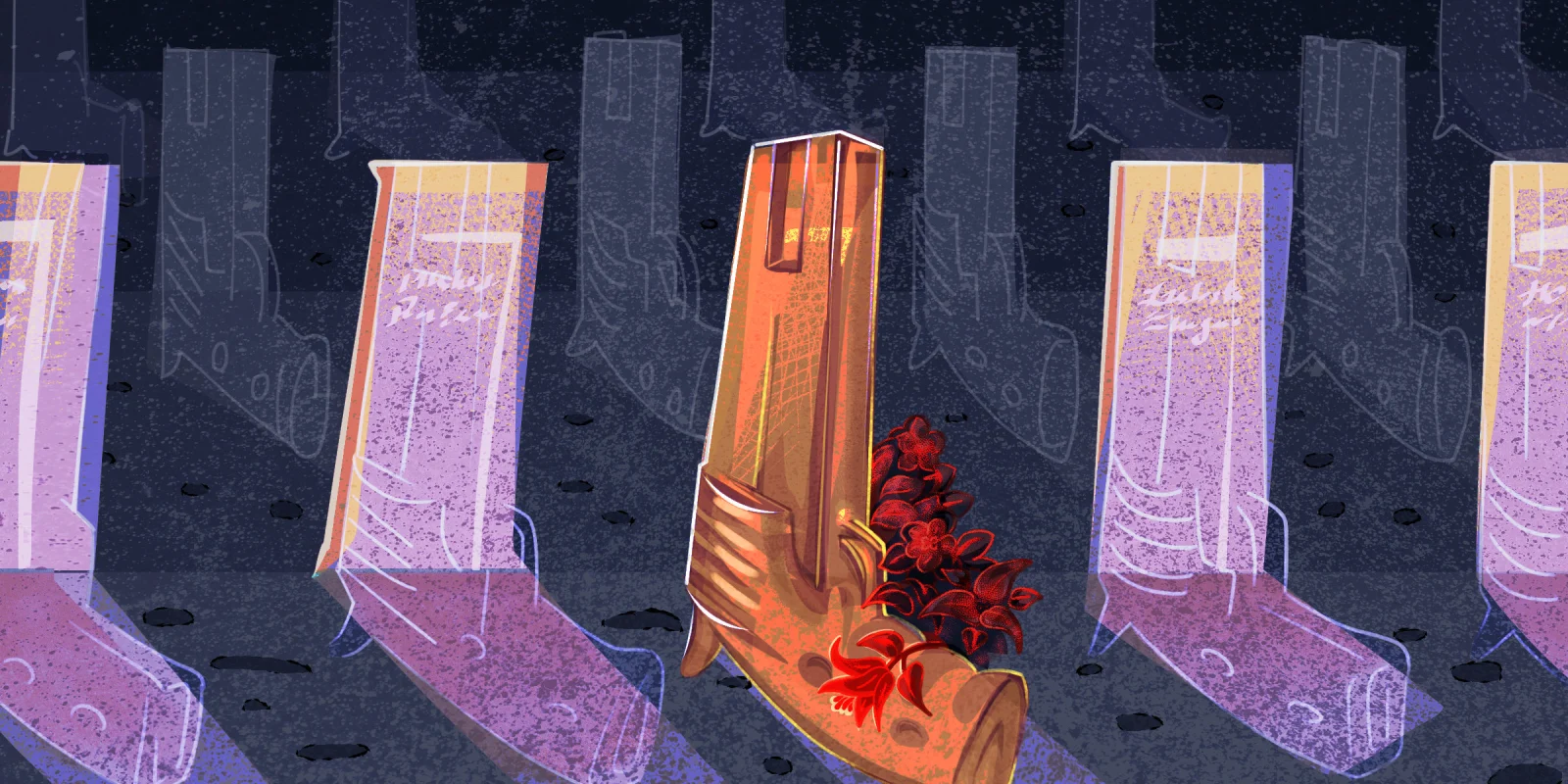

Illustration by April Brust