A suffocating feeling overwhelms my chest as the very core of my body begins to fail. I lie motionless, confined by the white walls of a hospital. Nothing could have prepared me for this moment. An 8-year-old boy about to grapple with an unfamiliar figure — the dark face of death approaching all too soon.

As the contrast enters through an IV line and circulates throughout my body, I immediately feel a disconcerting sensation. A sense of impending doom as the lungs that once breathed so much life and joy begin to fail me. Struggling to breathe, my heart and brain begin to race, searching for an escape. Tears form at the corners of my youthful eyes, unprompted yet present. I attempt to scream, but no sounds emerge from a throat that begins to close. I lie motionless, numbed by the very thought that, at 8 years old, I was facing an unexpected moment of suspense – the dying process. As the walls begin to close around me, I shut my eyes, expecting the cold winds of death’s descent to overcome me. But for reasons unknown, it chose not to come that summer day. Instead, a new vision was born the very moment my nearly dying eyes awakened.

At 8 years old, I had a near-death experience from a severe anaphylactic reaction to contrast dye during a routine CT scan in the first of many prolonged hospitalizations for pancreatitis. The memory of that experience remains so vividly rooted in me, preserved in the countless nightmares I had throughout my childhood. As I struggled to understand the concept and process of death regarding my own experience many years ago, I vowed to use my work as a physician to better embrace the art of dying as a means of healing from past trauma.

Twenty years later, I stand once again confined by the white walls of a hospital, immobilized by the very process of death once more playing out before me. Yet this time is different. I attempt to grasp why. Perhaps it is the MD title I bear across my chest, or perhaps it has to do with the nearly 20 years that have lapsed since my near-death experience as a patient.

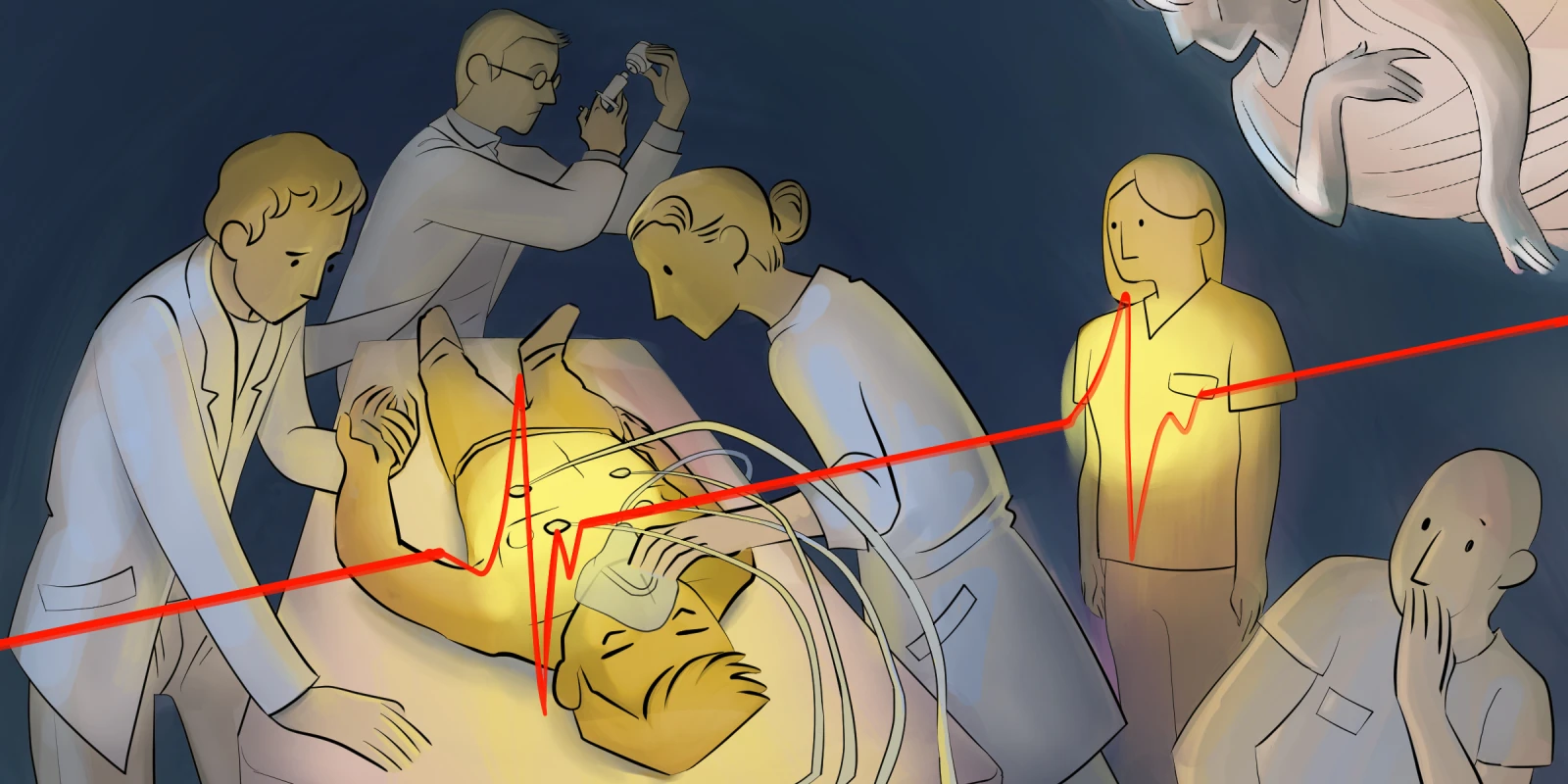

An elderly man lies on a hospital bed with a glazed expression, unaware of the chaos that surrounds him. Several rounds of resuscitation efforts are orchestrated; they yield diminishing returns as minutes pass by. It becomes apparent to all those in the room that this gentleman’s time has come. The cold winds of death descend to take this gentleman’s soul away, leaving behind only memories and legacy. Like my personal experience years ago, this sequence of events during my first patient death as a doctor will forever remain entrenched in my mind.

Fast forward a year and a half later, COVID-19 has overwhelmed hospital systems, crippled families, and devastated an entire nation with nearly 800,000 deaths. As a young doctor, COVID-19 became an important part of my growth and understanding of death. Alongside my colleagues, I felt each death on a deep and personal level. As the death count of COVID-19 patients I have treated continues to rise, I am reminded of the unique perspective I share both as a former patient once faced with death and as a key role player in the dying process of patients.

As with my experience as a young child, fear predominates the feelings of many of these patients and their families. The uncertainty surrounding the dying process drives much of this fear. And when death arrives without warning, many of our patients go into sensory overload, having to grapple with the mental anguish of accepting the dying process while feeling its physical ramifications. Nothing prepared me at the age of 8 for what I faced, and so now, as a doctor, I realize how imperative discussions regarding death are for patients and families.

Death is often viewed as failure in the work of healers. But I have found the contrary to ring true: Preparing one for the unpredictable nature of death and easing the process are the greatest gifts we can provide patients and their families. When we appropriately prepare our patients and their families, we can help ease their experience facing death. We can help alleviate some of the uncertainty behind death.

Once I accepted that we all face a mortality that can arrive without warning, I was able to truly appreciate what it meant to live. As a result, I was able to transform my fears into an appreciation for life, not only as a healer but also as a human being. I hope to dedicate my career to making that transformation possible for my patients and those I am privileged to serve.

What helps you face the tragedy of a patient's death? Share your experiences in the comment section.

Kazi I. Ullah, MD, is a third year internal medicine resident at Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, NY.

Illustration by April Brust