Physicians slide gracefully between the point of view of the molecule, the cell, the disease, the patient, the family, society, the doctor, and back again. They step outside themselves and their clearest, contracted roles so frequently that the act is oft forgotten, sporadically discussed, and rarely taught, trained, or exercised. The word, “knife,” carries synecdochal meaning, in part, because the object is just as useless deficient the blade as it would be absent the surgeon. Like placing a stethoscope in the correct interspace and interpreting the sound correctly, perspective is a skill, and as such, is augmented by talent and supported by practice. Perhaps a major distinction between the noble art of medicine and the stripped-down “healthcare provider” lies in the distinct ability and obligatory, if not altruistic, quest to better perceive health from outside oneself.

After all,

“A boil is no big deal…

on someone else’s neck.”

-Jewish Proverb

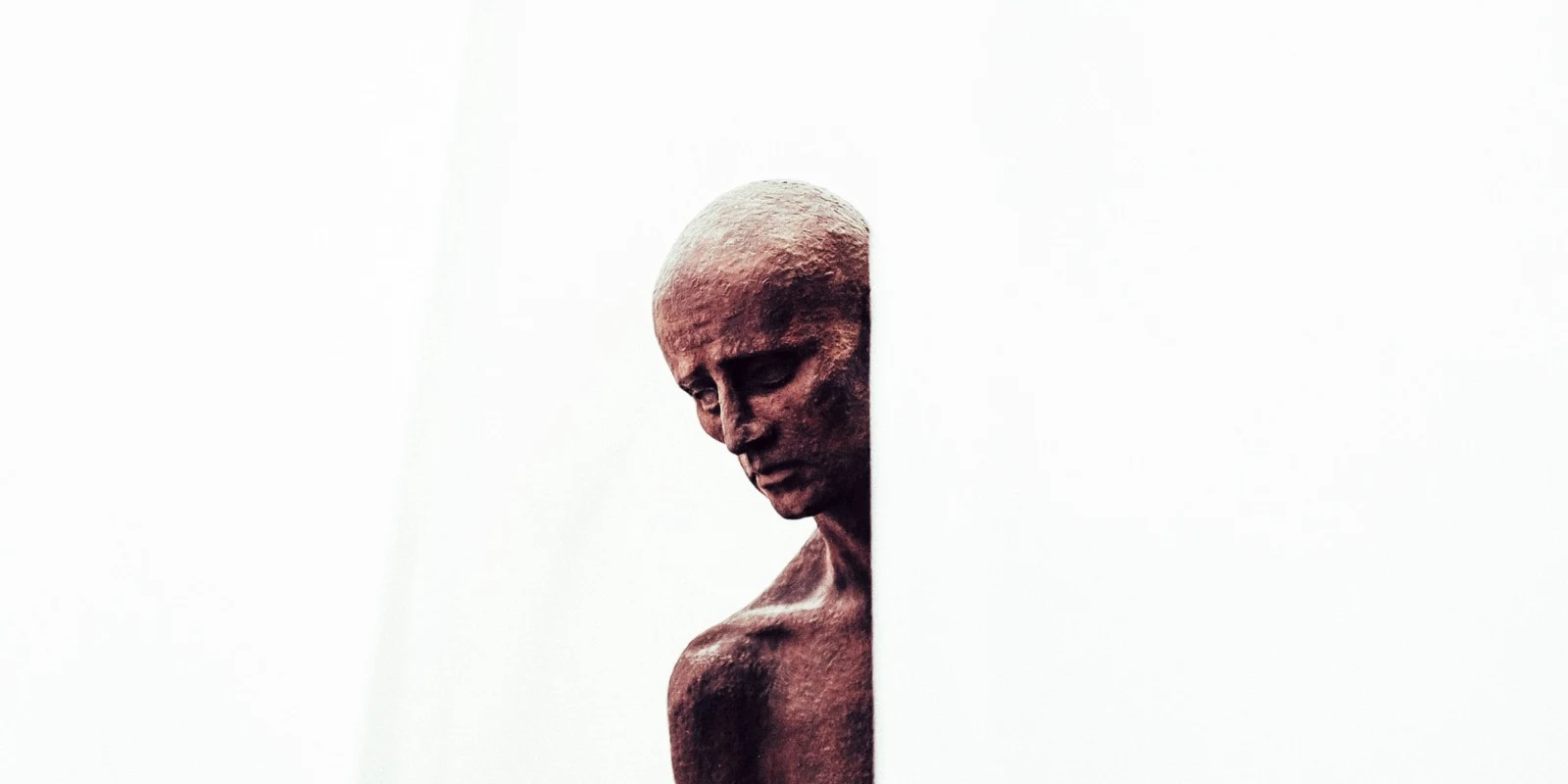

A single cell mutates and carries its aberrant genetics with each mitotic division. It finds a way to avoid the body’s protective mechanisms against over-proliferation and masks itself from safeguards that usually snuff out such behavior unmercifully. The progeny make a home, and multiply, unchecked, until biologic need overcomes intrinsic stores. Now, a mass amassed, an army of cells conspire to build a sustainable supply of nutrients via induction of vascular ingrowth and vessels inosculate at the borders of the invasion. The formed and fed rebel militia steals oxygen from a convoy of little red corpuscular passers-by and pillages proteins and electrolytes from a neighboring community of needy cells. On the three-dimensional reconstruction of a CT-angiogram, vessels ensnare the tumor the way the roots of an ominous tree on a rocky island would, drawing water from a stone.

Microscopically, it’s a beautiful symphony of interconnected processes that are as intricate as they are mischievous. Look close enough, and you can even appreciate a certain mysticism in the rare and clever circumstances that allow such a bleak incidence to occur. At an atomic level, life, in even the most violent and debilitating forms, exhibits a quiet resilience that connects it to the simpler, more pleasant phenomena of the universe — the flight mechanics of a dragonfly, arctic lichen thousands of years old, an amoeba on the back of a blue whale. But macroscopically, the force is destructive and unforgivable. It ulcerates, scars, and bleeds. What it doesn’t destroy or overtake, it distorts and deforms. Zoom out, and you find it causing tears to trickle down the contrastingly full, rosy cheeks of a spouse and an adult child. The emotion projects the deepest form of human pain — preempted loss peppered with uncomfortable reminders of the inevitability of personal mortality. The physician says, “yes, remove it as soon as possible.” The insurance company stamps the chart with, “requires pre-authorization.” The hospital says, “your block time is full.” The surgeon says, “I’ll do it Saturday A.M.” The act seems charitable to everyone but her husband and two children who had longstanding plans for brunch and a hike on that rare, free, weekend morning.

The jaw bone, usually sturdy, weakens until anything more solid than applesauce will fracture fragile remains, hardly more than a calcified shell at this point. By the time primary growth plateaus, it has hijacked facial animation and mastication, speech and swallow, and most of the respiration. In other words, it has stolen verbal and non-verbal communication, the satiety of hunger, thirst, breath, and social and emotional security; the very things that provide, sustain, and convey humanity. The toll taken transmits slowly from the anatomic to the psychological. If speech is lost, communication continues, but what of the less literal voice. If the airway is occluded, a tracheostomy is performed, but morning air, made sweet by humidity, can no longer flow naturally through the nasopharynx. If nutrition cannot be maintained, it can be provided directly to the digestive tract, but the flavor of a favorite fruit — gone, only a memory.

A regretful patient’s foot taps nervously on the submissive side of a large, oak desk in the oncologist’s office. The black bars that act as armrests make for a stylish chair, but they are cold. The words fall from the doctor’s mouth, and they are as weighty as one would expect. He glazes over the diagnosis and rushes to a treatment plan to avoid the awkward truth that earlier would have been much better. He only confirms what everyone suspected, but the body responds as if completely unprepared. The sympathetic nervous and adrenocorticotropic systems don’t flicker or give way, they flood the senses with a rush of hormonal and neuronal stressors. “This type of cancer…” is the last thing heard as the “fight or flight” response monsoons across once quiet planes. With nowhere to retreat but inward, that becomes the natural place to find respite and the doctor’s voice muffles in the manufactured distance like an adult on Charlie Brown.

The beauty of biology fades beneath the dark shade of clinical relevance and appreciation is quickly replaced with doubt, disappointment, and fear of the known. The doctor is baffled by the patient’s negligence. He knew what it was, why did he wait so long? Non-healing wounds and painful neck swelling are not a pestering fly that might buzz away if ignored long enough. A doctor’s appointment isn’t a box that, if left unopened, contains a diagnosis that is simultaneously cancer and not cancer. Disbelief and disdain boil up and are held at bay by a conflicting mixture of forced compassion, obligation to treat, and sincere concern. Can the philosophical power of denial possibly be strong enough to carry a patient to this level of pathology? The questions become increasingly less rhetorical and the answers more pointed:

Does he get to ask questions, or have opinions, despite clear self-neglect? Yes. He smoked because that’s what people did at the time. He drank because, well, he liked to. He waited because he was afraid.

To what extent is he entitled to complain over poor outcomes? He has every right.

Has it spread? Probably.

Can it be obliterated? Potentially.

Will it be removed? Mostly.

Can there be a long-term cure? Unlikely.

Can we prolong life? Almost certainly.

Can we improve quality of life? Almost certainly.

Can it be reconstructed? In a way.

The diagnosis, treatment, and reconstruction will be costly. The patient and the patient’s family have no money. Uncontrolled pain leads to unworked hours, incurring unpaid bills, and eventual loss of insurance. The physician, the hospital, and the taxpayer will foot the bill. Is it unfair? Do you feel differently if you are the patient (suspend disbelief and ignore the instinctive certainty that you would never be in such a situation)?

The treatment plan is so matter-of-fact, so black and white, so algorithmic, so dry that it takes work to be afraid of it. It takes perseveration on the worst clinical outcomes to really believe they are possible. When the doctor says there is a 95% chance of survival at 5 years, the patient thinks “Phew, that’s pretty good odds,” and ignores the truncated, qualifying timeline and the five of every hundred patients who thought the same and met dismay. When the physician lays out a 55% chance of particular adverse effects of treatment, the patient thinks, “Phew, almost a 50-50 chance of no side effects.” The mind fills in the negative space the way it does whn vwls r rmvd frm wrds and not a beat is missed. Impressive feats of mental gymnastics are performed to allow psyche-protecting willful ignorance and plausible deniability. Consents are signed, and treatment begins.

Tamed grays of radiation, once feared for cancer-causing properties, bombard the building blocks of life and capitalize on the rapid, irregular rate of cellular turnover in tumor growth. The more duplications, the more chance of error; like a copy of a copy during an earthquake. The local effects of radiation to the skin and vasculature are brutal and unpredictable. Chemotherapeutics take similar advantage, but, often less directed, they come with collateral damage to naturally high-turnover tissues — hair follicles, stomach and oral lining, vital blood cells. Thinned hairlines the shower drain, soupy vomit lines bouncing water floating in cool porcelain, and semi-translucent orange, white-topped bottles containing everything from anti-emetics to antibiotics line the nightstand by the bed. A spouse reads a book in a nearby rocking chair to pass the time while taking FMLA-sanctioned leave. The oncologist reviews clinical trial protocols late into the night at the office. The surgeon reviews complex anatomy while stroking the hair of a four-year-old who lays in her lap but should have been in bed an hour ago. At tumor boards, they argue over the best course of action, sometimes with collegiality and sometimes less so.

There is no happy ending. Not this time. The tumor flourishes until it takes too much and leads to its own, and its host’s, demise. All at once, cells decay and the distinction between healthy and unhealthy disappears. Cellular remains are broken down into molecules and atoms that recycle into the universe’s theoretical conservation of mass. The medicine and physicians failed, as they always do on a long enough timeline. They attempt to find comfort in prolonging life but are nagged by the question of quality and only modest solace is found in the effort. The oncologist goes to happy hour with friends. The surgeon surprises her family by planning a camping trip to make up for the missed Saturday outing several months ago. The patient’s family enters and exits each of the stages of grief before moving on to the next comedy, drama, or tragedy that life has in store. The tissue is banked for research. Bills go unpaid. The earth spins on its axis. And you know yourself just a little bit better.

“If you can learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.”

— Atticus Finch in “To Kill A Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

How much of success, as a physician, is intimately tied to the fluidity of perspective? Can you forgive yourself for complications? Can you forgive your patient for neglecting preventative care? Can you forgive nature for its cruelty? Can you laud your efforts? Can you see the internal struggles and fears overcome by a patient who presented too late? Can you find the beauty in nature’s flaws? And, when the answer is yes, should you? Physicians are charged with understanding the mechanics of pathology and the technological and pharmaceutical barriers confining their ability to combat it. They are asked to empathize, sympathize, and provide compassionate care to the patient and the peri-patient personalities; no small emotional task. They go to work and fulfill the multi-faceted mission of health care, and, still, go home as a physician, scientist, perhaps a parent, a friend, sometimes a patient themselves, but always a person. This movement, role-to-role, perspective-to-perspective, necessitates practice, perception, and a healthy dose of intro- and extrospection. Physicians, knowingly or unknowingly, develop a profound, complex understanding of what and who we are to medicine and, in a global sense, what medicine is to us. They achieve this end by sliding gracefully between the point of view of the molecule, the cell, the disease, the patient, the family, society, the doctor, and back again.

Joshua J. Goldman, MD is a recent graduate of Integrated Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (PRS) at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Medicine and is currently an Integrated Craniomaxillofacial and Microsurgery Fellow at Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak. His professional interests, outside PRS, include healthcare advocacy, device innovation, digital marketing, ethics, medical education, and physician wellness. You can follow him on instagram at @GoldStandardPlasticSurgery. He is also a 2018–19 “Doximity Author.”

The above represent his experience and viewpoints alone. They are not representative of his institution, program, or hospital. They are not to be construed as medical advice. Dr. Goldman has no conflicts of interest to disclose.